(Update 17/10/16: I’ve just read Borges’ ‘Partial Magic in the Quixote’ in Labyrinths and made a few notes about it, here).

This is another book that I’m reading for 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die., but I’ve been meaning to read it since I was a teenager. I don’t have a copy, so I’m reading it through DailyLit.com which I’m finding is a good source of out-of-print titles and much easier on the eye than Project Gutenberg. (Mind you, Daily Lit doesn’t do much in the way of out-of-print OzLit, so it’s a good thing there’s Project Gutenberg Australia for that.)

Anyway, my first discovery is that I’ve been calling this author by the wrong name for 40 odd years. His proper name, according to Wikipedia, is Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616), and I ought to remember that it’s de Cervantes, not just Cervantes. He is Spain’s most influential poet, playwright and novelist, and is clearly essential reading before I jet off for Spain next year (global economic crisis permitting, that is).

I must admit that my heart sank a little when I saw the Author’s Preface, but it is much shorter than Jonathan Swift’s, and easily comprehended. A Preface should be impressive, but his is not, and does not need to be, says his friend, because his subject is a simple man and it is a simple story.

As this piece of yours aims at nothing more than to destroy the authority and influence which books of chivalry have in the world and with the public, there is no need for you to go a-begging for aphorisms from philosophers, precepts from Holy Scripture, fables from poets, speeches from orators, or miracles from saints; but merely to take care that your style and diction run musically, pleasantly, and plainly, with clear, proper, and well-placed words, setting forth your purpose to the best of your power, and putting your ideas intelligibly, without confusion or obscurity. Strive, too, that in reading your story the melancholy may be moved to laughter, and the merry made merrier still; that the simple shall not be wearied, that the judicious shall admire the invention, that the grave shall not despise it, nor the wise fail to praise it.

Chapter One explains that a gentleman obsessed by books about chivalry loses his wits through trying to understand the incomprehensible nonsense in them:

“the reason of the unreason with which my reason is afflicted so weakens my reason that with reason I murmur at your beauty;” or again, “the high heavens, that of your divinity divinely fortify you with the stars, render you deserving of the desert your greatness deserves.”

and as we all know, he decides therefore to become a knight himself.

His preparations are handicapped by his modest means, a lack of skill and a complete failure to understand the purpose of the equipment he needs. He cleans the rust from his grandfather’s armour, and, perceiving the lack of a helmet, makes one from pasteboard. Its flimsiness is apparent even to him, so he reinforces it with iron bars (which he later discovers make it difficult to get the helmet off). He spends four days dreaming up an impressive name for his hack, settling at last on Rocinante, a name he considers to be ‘lofty, sonorous, and significant of his condition as a hack before he became what he now was, the first and foremost of all the hacks in the world’. He then takes a further eight days to christen himself Don Quixote de la Mancha, and was then ready for a quest, the most obvious being to find a lady to be in love with….

His choice falls upon a farm-girl who lives nearby and he dubs her Dulcinea del Toboso so that she too has a name to suit her significance as The Lady of His Thoughts. Aldonza Lorenzo herself has no idea that she is the object of his affections.

So, onto Chapter 2.

Oh, poor Don Quixote! He sets off, a little anxious that he has not yet been dubbed a knight by anyone, and travels all day without any sign of any ‘wrongs … to right, grievances to redress, injustices to repair, abuses to remove, and duties to discharge.’ When he reaches an inn, his wits further addled by the heat, he mistakes it for a castle, and submits himself to the mocking administrations of a pair of baggages and the crafty innkeeper. Chapter 3 descends into high farce as the landlord agrees to perform the dubbing, and sets Don Quixote to watch his armour all night long in the courtyard where amused locals come to watch the entertainment. Alas, local carriers fail to show the requisite respect for the armour, and so Don Quixote must needs attack them with his lance, causing considerable damage – for which the innkeeper takes no responsibility since he had warned everyone that his guest was quite mad. He was, nevertheless, keen to see the back of Don Quixote so there is a droll ceremony and he is sent on his way.

It was at this point that I began to wonder why this amusing but so-far not especially riveting tale merits its reputation, so I checked out Wikipedia. It is, after all, held by some to be the first novel (though some would claim Voltaire’s novella Candide for that) . This is what it says:

The novel’s structure is in episodic form. It is a humorous novel in the picaresco style of the late sixteenth century. The full title is indicative of the tale’s object, as ingenioso (Spain.) means “to be quick with inventiveness”.Although the novel is farcical, the second half is more serious and philosophical about the theme of deception. Quixote has served as an important thematic source not only in literature but in much of art and music, inspiring works by Pablo Picasso and Richard Strauss. The contrasts between the tall, thin, fancy-struck, and idealistic Quixote and the fat, squat, world-weary Panza is a motif echoed ever since the book’s publication, and Don Quixote’s imaginings are the butt of outrageous and cruel practical jokes in the novel. Even faithful and simple Sancho is unintentionally forced to deceive him at certain points. The novel is considered a satire of orthodoxy, truth, veracity, and even nationalism. In going beyond mere storytelling to exploring the individualism of his characters, Cervantes helped move beyond the narrow literary conventions of the chivalric romance literature that he spoofed, which consists of straightforward retelling of a series of acts that redound to the knightly virtues of the hero. [1]

There are puns, some of which are recognisable even in translation, allusions and irony, but it was also the characterisation of ordinary people that is said to be new. (Chaucer did that in the 15th century in The Canterbury Tales, though that’s poetry, not a novel.)

Chapter 5 brings Don Quixote his first wrong to right, but satisfaction is brief. A farm boy has been tied up to a tree as punishment for demanding his wages, and threats with the lance force the farmer to pay up. As soon as Don Quixote turns his back however, the boy is beaten and tied up again, but his rescuer is oblivious, too busy accosting some Toledo traders who have dared to insult his beloved Dulcinea. Alas the knight-errant takes a tumble, gets a kick in the ribs for his trouble and has to be rescued by a kindly peasant from his own village.

Back home, Don Quixote is deprived of his books of chivalry. His curate and his barber decide that it is reading about chivalry that has caused the mischief, so they burn most of them and seal up the remainder behind a plaster wall, this architectural reconfiguration confusing Don Quixote still further. (Cervantes is, of course, making the point that the books are innocent, with which assertion I naturally agree). Undaunted, however, Don Quixote persuades Sancho Panza, a farm labourer, to set out with him on his second sally in Chapter 7. It is in Chapter 7 that our hero meets those legendary windmills, from which the saying ’tilting at windmills’ passed into our language. From there he attacks two Benedictine monks and a Biscayan peeved by the assault on his travel plans – and then we readers are briefly left in the lurch until the narrator comes by chance upon another set of documents recording the adventures of Don Quixote, and thus begins Part 2.

It was at this point that I went surfing the web for a little light music, and found a video from the 57th Tony Awards, with Brian Stokes Mitchell capturing perfectly the pathos of Don Quixote in the musical, Man of La Mancha

BUT Update 2.5.10

I have had to remove it from here because it was apparently a violation of copyright, something I was not aware of when I posted it. At this stage a lovely version of the serenade to Dulcinea by Placido Domingo, notable for the paintings that accompany the song, is still available, but maybe not for much longer because You Tube is gradually removing this type of music video.

Heavens! There are 420 odd Daily Lit episodes to go, so I think I’ll publish now and add more to this post as I go along….

Update June 5th 2009

Part 2 begins with the tale of the beautiful Marcela, daughter of Guillermo the Rich, who took it into her head to go wandering about dressed as a shepherdess and met, as a consequence, Chrysostom, who had taken it into his head to go wandering about dressed as a shepherd even though he was a scholar and also (by the standards of the village) very rich. He, like the other young men of the village, falls for her, but uppity young woman that she is, ‘her scorn and her frankness bring them to the brink of despair’. When Chrysostom dies, he leaves instructions in his Will that ‘he is to be buried in the fields like a Moor, and at the foot of the rock where the Cork-tree spring is, because, as the story goes (and they say he himself said so), that was the place where he first saw her’ but this and other instructions are considered pagan by the village priest and there is great consternation in the village about what to do. Naturally, Don Quixote feels obliged to attend. His companions, naturally, having realised that he is quite mad, amuse themselves by giving him ‘an opportunity of going on with his absurdities’.

Yet not all of what Don Quixote says is entirely absurd. This second part of the book explores philosophical issues and it is interesting to see that as long ago as the early 17th century, Cervantes was addressing himself to moral culpability in war, an issue which was dealt with at the Nuremburg Trials and resonated again at Abu Ghraib. Cervantes wrote that the soldier ‘who executes what his captain orders does no less than the captain himself who gives the order’ .

It is here also that we see the saying ‘one solitary swallow does not make summer’, more commonly now quoted in English as ‘One swallow does not a summer make’, meaning that one cheering portent does not mean that all is well, or alternatively, that one ought not jump to conclusions. I shall not, therefore, jump to the conclusion that Cervantes was familiar with Aristotle. Nothing much is known about his early life or education, so the influences on his work can only be speculative…

Alas, the tale of Chrysostom and Marcela goes on for rather a while, and Chrysostom’s plaintive verses about his travails with Marcela didn’t interest me at all. Rather, I found myself agreeing with Marcela, who, like every other victim of the unaccountable passion of stalkers, quite rightly asserts that she is under no obligation to put up with them.

I was born free, and that I might live in freedom I chose the solitude of the fields; in the trees of the mountains I find society, the clear waters of the brooks are my mirrors, and to the trees and waters I make known my thoughts and charms. I am a fire afar off, a sword laid aside.

Those whom I have inspired with love by letting them see me, I have by words undeceived, and if their longings live on hope–and I have given none to Chrysostom or to any other–it cannot justly be said that the death of any is my doing, for it was rather his own obstinacy than my cruelty that killed him; and if it be made a charge against me that his wishes were honourable, and that therefore I was bound to yield to them, I answer that when on this very spot where now his grave is made he declared to me his purity of purpose, I told him that mine was to live in perpetual solitude, and that the earth alone should enjoy the fruits of my retirement and the spoils of my beauty; and if, after this open avowal, he chose to persist against hope and steer against the wind, what wonder is it that he should sink in the depths of his infatuation? If I had encouraged him, I should be false; if I had gratified him, I should have acted against my own better resolution and purpose. (Chapter 14)

Ironically, it is the ‘mad’ Don Quixote who agrees with her, and prevents the other shepherds from following her when she retreats to the forest. Naturally, he considers himself exempt from such constraints, but fortunately for Marcela he gets lost in the forest before he can harass her. Alas, en route his placid steed Rocinante took a fancy to ‘a drove of [female] Galician ponies belonging to certain [20+] Yanguesan carriers’ resulting in an altercation which notwithstanding Don Quixote’s proud boast ‘I count for a hundred’ leaves Sancho Panza, Don Quixote and Rocinante ‘a sorry sight and in sorrier mood.’ It falls to Sancho Panza to tend to his master because a knight-errant feels his wounds more, it seems, and they make their way to an inn, quarreling en route because Don Quixote is convinced that it is a castle…

There follows high farce when one of the serving girls arrives in the garret to complete her assignation with a carrier, only to have Don Quixote perceive her to be nobly born, and much in love with him. When in the darkness she encounters the arms of the knight-errant, he gently breaks it to her that his heart belongs to Dulcinea, but the carrier, who understands not a word of what is going on is outraged and

not relishing the joke he raised his arm and delivered such a terrible cuff on the lank jaws of the amorous knight that he bathed all his mouth in blood, and not content with this he mounted on his ribs and with his feet tramped all over them at a pace rather smarter than a trot. The bed which was somewhat crazy and not very firm on its feet, unable to support the additional weight of the carrier, came to the ground, and at the mighty crash of this the innkeeper awoke and at once concluded that it must be some brawl . (Chapter 14)

In a panic the girl leaps into bed with Sancho Panza and there is pandemonium. A cuadrillero (variously translated as a group leader, a hooligan or a team worker) intervenes and poor old Pancho comes off worst again. Chastised, the cuadrillero whacks Don Quixote as well; both victims drink the Don’s ‘curative’ balsam, multiplying Pancho’s troubles yet further so that it is Quixote who must saddle up the horse. At this point the innkeeper demands payment, Don Quixote refuses on the grounds that knights don’t have to pay for lodgings, and Sancho cops a ‘blanketing’ (Chapter 17). All his entreaties that they might return home for the harvest fall on deaf ears, and they set off again, only to meet up with two advancing armies to be vanquished. The ‘armies’ turn out to be flocks of sheep, and the shepherds take a dim view of Don Quixote’s attack. Having knocked out some of his teeth, they depart, and further imbibing of the restorative balsam leave both Sancho Panza and his master in such a state that Panza decides he’s had enough and will go home.

In Chapter 19 they meet up with a burial party, but (as somehow by now we knew he would) Don Quixote ‘took it into his head that the litter was a bier on which was borne some sorely wounded or slain knight, to avenge whom was a task reserved for him alone’ and to the reader’s astonishment succeeds in routing them. They turn out to be priests, who promptly excommunicate him and Sancho dubs him ‘The Knight of the Rueful Countenance’ thereafter. I began to notice, at this point, just how democratic the interchanges between these two adventurers were – which must surely have been almost subversive at a time when rank was determined at birth and immutable. While still subservient to Don Quixote, Sancho speaks freely to him, and (albeit with deference) not only challenges his mad ideas, but also tries to subvert them, as for example when he hobbles Rocinante so that Don Quixote can’t rampage off into the night to attack what turns out to be ‘fulling hammers’ (whatever they might be).

His next victim is a barber, thought to be a discourteous knight, by which means they acquire a basin for a helmet and his abandoned grey horse. Quixote frees some galley slaves (the king’s prisoners) but gratitude is wanting (Chapter 22)and once again they find themselves relieved of their possessions, all but poor Rocinante (for whom I feel more pity than the two adventurers). (By now I was getting a bit tired of these picaresque adventures and I was only up to Episode 74 of 454, but what could I do but press on? Such is the pressure imposed by the 1001 Books list LOL).

In Chapter 23 they come upon an abandoned satchel, filled with clean linen shirts, some money and a sonnet. This leads to an altercation with the ‘Knight of the Ragged Countenance’ (Cardenio) and while The Knight of the Rueful Countenance doesn’t ‘smell a rat’ this reader certainly did. He too has a lady love, (Luscinda) he too is frustrated in his devotions, and he too has read a book of chivalry. In pursuit of this mad knight, Sancho Panza admits his suspicions: ‘All you tell me about chivalry, and winning kingdoms and empires, and giving islands, and bestowing other rewards and dignities after the custom of knights-errant, must be all made up of wind and lies, and all pigments or figments, or whatever we may call them’ (Chapter 25) and this leads to an admission that the Lady Dulcinea is none other than the peasant girl Aldonza Lorenzo, well-known to Sancho Panza:

The whoreson wench, what sting she has and what a voice! I can tell you one day she posted herself on the top of the belfry of the village to call some labourers of theirs that were in a ploughed field of her father’s, and though they were better than half a league off they heard her as well as if they were at the foot of the tower; and the best of her is that she is not a bit prudish, for she has plenty of affability, and jokes with everybody, and has a grin and a jest for everything. (Chapter 25)

With a letter to Aldonza and an order for three asses in his pocket (or so he thinks), Sancho beats a hasty retreat on Rocinante, for he has had enough. Alas when confronted by the barber and the curate from his own village who suspect him of having robbed Don Quixote, it turns out that he has neither the papers nor recollection of his orders. They set up an elaborate deception to delude Don Quixote but meet up instead with Cardenio (of the Ragged Countenance) and there follows a farce worthy of a 19th century melodrama.

And I am up to Episode 101 of 454 and sorely in need of a rest! It is amusing, but like many a running gag before and since, it becomes tiresome. I shall take a break and press on next weekend….

Update 27.6.09

When the curate, Master Nicholas the barber, the Princess Micomicona (Dorothea) and Cardenio all gang up Don Quixote – what hope does he have? I begin to feel intense pity for the poor man, which may not have been the effect intended by Cervantes at all. Dorothea (satirising books about chivalry with great aplomb) sets him up to deal with Pandafilando of the Scowl, to ‘slay him and restore to [him] what has been unjustly usurped’ thereby gaining her hand in marriage and a kingdom to please Sancho besides. ‘Which of the bystanders could have helped laughing to see the madness of the master and the simplicity of the servant?’ Which indeed? For Don Quixote remains loyal to his beloved Dulcinea, and Sancho is not at all happy to see his prospects dashed for a simple peasant girl. The dispute is resolved when who should arrive on the scene but Pasamonte on Sancho’s beloved Dapple, and when he flees, Sancho is mollified when the ass is restored to him.

Their relationship restored, Don Quixote quizzes Sancho about the delivery of the letter to Dulcinea, and has a ready answer for every observation that Sancho has about the lady (who, of course, he has never seen).

“In saying I cursed my fortune thou saidst wrong,” said Don Quixote; “for rather do I bless it and shall bless it all the days of my life for having made me worthy of aspiring to love so lofty a lady as Dulcinea del Toboso.”

“And so lofty she is,” said Sancho, “that she overtops me by more than a hand’s-breadth.”

“What! Sancho,” said Don Quixote, “didst thou measure with her?”

“I measured in this way,” said Sancho; “going to help her to put a sack of wheat on the back of an ass, we came so close together that I could see she stood more than a good palm over me.”

“Well!” said Don Quixote, “and doth she not of a truth accompany and adorn this greatness with a thousand million charms of mind! But one thing thou wilt not deny, Sancho; when thou camest close to her didst thou not perceive a Sabaean odour, an aromatic fragrance, a, I know not what, delicious, that I cannot find a name for; I mean a redolence, an exhalation, as if thou wert in the shop of some dainty glover?”

“All I can say is,” said Sancho, “that I did perceive a little odour, something goaty; it must have been that she was all in a sweat with hard work.”

“It could not be that,” said Don Quixote, “but thou must have been suffering from cold in the head, or must have smelt thyself; for I know well what would be the scent of that rose among thorns, that lily of the field, that dissolved amber.”

At this point they meet up again with Andres (the lad that Quixote had ‘saved from his master’) and upon hearing that the intervention had got him a flogging instead, Don Quixote determines to seek justice for him again – after he has finished his quest for Dorothea. No thanks, says Andres, and beseeches him: ‘For the love of God, sir knight-errant, if you ever meet me again, though you may see them cutting me to pieces, give me no aid or succour, but leave me to my misfortune, which will not be so great but that a greater will come to me by being helped by your worship.’ They then make their way back to the inn where Dorothea and her team regale the crowd with Don Quixote’s misadventures, where follows an odd interlude involving books of chivalry, which are the cause of Don Quixote’s madness.

Some of the people at the inn say that they too like books of chivalry and believe in the tall tales told, and when the landlord brings forth some from his collection, the curate determines to burn them. I suspect that the titles mentioned are some sort of literary payback by Cervantes, but the curate is persuaded to read them – and falls prey to the same enchantment as the others. (Though they don’t rush to become knight-errants like Don Quixote.)

The story within the story is set in Florence and is titled ‘The Ill-Advised Curiosity’. The character Lothario [2] who falls in love with his best friend’s wife Camilla predates the Lothario of Nicholas Rowe’s play by a century (though the inference is the same: women are easily seduced by sexy men, music, verse and the folly of husbands who fail to trust them). It is a very long story indeed, tempting this reader to think that perhaps Cervantes recognised that Don Quixote’s adventures were beginning to pall and a diversion was needed. There are some sonnets included in this little romance, but they are parodies. I did like the maid Leonela’s alphabet of true love!

He is to my eyes and thinking, Amiable, Brave, Courteous, Distinguished, Elegant, Fond, Gay, Honourable, Illustrious, Loyal, Manly, Noble, Open, Polite, Quickwitted, Rich, and the S’s according to the saying, and then Tender, Veracious: X does not suit him, for it is a rough letter; Y has been given already; and Z Zealous for your honour.” (Chapter 34)

Alas Lothario sees the saucy Leonela’s lover exit the house, naturally assumes that Camilla has betrayed him, and dobs her in to Anselmo. His dismay serves him right because he set up Lothario to test Camilla’s virtue in the first place. He agrees to hide himself behind some tapestries to witness her perfidy, but Lothario thinks better of his unchivalrous behaviour, goes to see Camilla to confess and discovers that he was mistaken in his assumptions about Leonela’s lover. (How many plays and operas have been based on this scenario, eh?) Naturally ‘he entreated her pardon for this madness, and her advice as to how to repair it, and escape safely from the intricate labyrinth in which his imprudence had involved him’ and between the two of them they achieve this, with only a small amount of blood shed, and harm only to Lothario’s conscience.

The conclusion to this story is interrupted however when Don Quixote attacks some wine skins in his room, even Sancho ‘so much had his master’s promises addled his wits’ believing them to be ‘the giant, the enemy of my lady the Princess Micomicona’ (Chapter 35). Everyone (except the landlord) thinks this is terribly funny, and Sancho is consoled by Dorothea who promises him his share of the kingdom before long.

Cervantes then resumes the story of Camilla, Lothario and Anselmo. As seemed inevitable the cuckolded husband finally discovers the truth and the guilty couple flee, prudently taking Camilla’s jewels with them. Hot on their heels, Anselmo suffers a fatal indisposition, and on his death-bed forgives his errant wife. As any good wife should, she immediately saw the error of her ways, and spent the rest of her days in a convent. (The curate is not impressed: he can’t believe any husband could be so foolish.)

Just at this moment a new party enters the inn, and much to the astonishment of all Dorothea is reunited with her seducer Fernando, and Cardenio is reunited with his lover Luscinda. Things are about to get out of hand when Dorothea says:

“What is it thou wouldst do, my only refuge, in this unforeseen event? Thou hast thy wife at thy feet, and she whom thou wouldst have for thy wife is in the arms of her husband: reflect whether it will be right for thee, whether it will be possible for thee to undo what Heaven has done, or whether it will be becoming in thee to seek to raise her to be thy mate who in spite of every obstacle, and strong in her truth and constancy, is before thine eyes, bathing with the tears of love the face and bosom of her lawful husband.” (Chapter 36)

A digression of my own

By now I was somewhat confused, and had forgotten the plot details from Part One. A search of the net was necessary to restore order…

Thank goodness for Spark Notes! Obviously Don Quixote is a set text at college or university level, and much to my surprise the entire study guide is online. Even so, it took a while for me to get back on track, and I begin to wonder just how long this post will eventually be. I am less than one quarter of the way through the story, and am still finding that I need to retell it in order to remember what’s going on. If anyone in cyberspace is plodding through this with me, I can only commend your patience and suggest that you find something better to do!

Resuming the plot…

Things are sorted out, love triumphs (sort of) but Sancho is not best pleased because Dorothea is not going to bequeath him a kingdom and what’s worse, Don Quixote has slept through the whole thing (perhaps because of the wine fumes). Perhaps because they are in love and contented, the rest of the party begin to plan ways of getting Don Quixote home without making a mockery of him – without him realising that there has been a change of plans.

Update July 4th 2009

I admit that by now I am well and truly tired of Don Quixote and not much interested in his ‘droll adventures’ with the ‘famous Princess Micomicona’ or anybody else, but my interest picked up when I started reading Cervantes views about the power of letters versus the power of arms.

Letters say that without them arms cannot maintain themselves, for war, too, has its laws and is governed by them, and laws belong to the domain of letters and men of letters. To this arms make answer that without them laws cannot be maintained, for by arms states are defended, kingdoms preserved, cities protected, roads made safe, seas cleared of pirates; and, in short, if it were not for them, states, kingdoms, monarchies, cities, ways by sea and land would be exposed to the violence and confusion which war brings with it, so long as it lasts and is free to make use of its privileges and powers. (Chapter 37)

Cervantes goes on to say that no amount of wretchedness as a student can compare with what is experienced by soldiers and sailors, and the wonder of it is that there are always more young men to take the place of the fallen. He is especially affronted by the invention of artillery:

Happy the blest ages that knew not the dread fury of those devilish engines of artillery, whose inventor I am persuaded is in hell receiving the reward of his diabolical invention, by which he made it easy for a base and cowardly arm to take the life of a gallant gentleman; and that, when he knows not how or whence, in the height of the ardour and enthusiasm that fire and animate brave hearts, there should come some random bullet, discharged perhaps by one who fled in terror at the flash when he fired off his accursed machine, which in an instant puts an end to the projects and cuts off the life of one who deserved to live for ages to come.

These comments surprise the company because they are so used to Don Quixote talking nonsense about chivalry. It puts the company in a good mood, ready to listen to the tale of the Spaniard and his Moorish lady companion, which turns out to be another story within a story. He is one of three brothers, who received their inheritance early on condition that they went into the church, the military or commerce. The ‘Spaniard saw service for the King and was captured and enslaved by the Ottoman Turks. Eventually the opportunity arises to be ransomed, and with him goes the Moorish lady Zoraida who has heard the word of the Lord, is keen to convert to Christianity (and gives him the requisite money). (Chapter 40) They make their escape, her father throwing himself into the sea when he discovers her apostasy and they are subsequently raided by French pirates and set adrift. (Chapter 41) Truly the quest to save this lady from the infidels is clearly one to which Don Quixote might aspire!

Anyway they land safely, meet up with the Spaniard’s uncle and set off for Granada, which is where they meet up with Don Quixote and the company….there is some to-ing and fro-ing but all ends happily when two of the three brothers are reunited (the third having made lots of money in Peru) and plans are made to set off for Seville where Zoraida can be baptised and the marriage can take place. The only problem is that it is Don Quixote who is on guard outside overnight…..(Chapter 42)

A muleteers sings below, waking and upsetting Clara (daughter of the brother who’s a Judge) – because he’s not a muleteer, he is Don Luis, a lord, and she (aged 15) is lovestruck. Alas, the mischief-makers from the inn decide to provoke Don Quixote into more folly. They beseech him to hold hands, and then tie him to the bolt of the door – and he of course thinks it is enchantment. (Chapter 43) Four travellers arrive, there is a ruckus because Don Quixote thinks the inn is a castle, he challenges combat but is snubbed because the landlord sets the new arrivals straight about things, and they continue in their pursuit of the ‘muleteer’. They turn out to be the servants of Don Luis’s father and they have instructions to take him home instead of mooning about after Dona Clara. At the same time there is a punch-up outside the inn because some of the guests have taken advantage of the confusion and tried to leave without paying, and the landlord’s daughters beseech Don Quixote to help. (Which is a bit of a cheek, considering they had just recently tied him up!) He however is determined not to get involved in anything else without the permission of ‘Princess Micomicona’ because he has promised to restore her to her kingdom. Dorothea, of course, gives permission, but still he hesitates (because the combatants are very large and strong), and calls for Sancho. Eventually order is restored without further fisticuffs, while at the same time the Judge has got the truth out of Don Luis and is keen for him to marry Dona Clara because he fancies having a title. (Chapter 44)

Peace seems restored, but the barber turns up again and wants his basin and pack-saddle back again. The basin is bandied about as Mambrino’s helmet, won fair and square in war, and those who think it’s funny to go along with Don Quixote’s fancies vote in his favour while those who haven’t a clue about what’s going on get very cross indeed. There is a major furore, and Don Quixote ends up being arrested as a highwayman. The curate intercedes, the barber is paid for his basin, the servants who want to escort Don Luis home agree that three will go back and explain while the fourth accompanies him to happiness with Don Fernando, the landlord’s bills are paid and all seems well in the world.

Don Quixote is now ready to continue with his quest, but Sancho has had enough and denounces Dorothea as a courtesan rather than a queen of a great kingdom. The company has had enough of his nonsense too, so that although Sancho is made to apologise, they decide to send Don Quixote back to his village without further ado, and cage him on a cart to send him on his way, complete with escort (in disguise). He is persuaded to submit to this by a prophecy that reunites him with Dulcinea – though of course Sancho is not deluded. (Chapter 47). When a canon comes upon them he denounces the curate and his friends, but the curate lays the fault at the foot of the books of chivalry, which are responsible for all the madness in the world. There is then a very long dissertation about chivalry and why books about it are a bad thing, while Sancho is busy persuading Don Quixote that his enchantment is a trick. He gets permission for Don Quixote to be released for a little while, and the Canon tries to make him renounce chivalry to no avail. (Chapter 50)

Update July 7th – progress!

Well, well…I started this epic on May 22nd and here I am in July and I’ve just made it to Volume 2.

AMENDMENT March 16th 2014

At this point, you should abandon what is basically just a plot summary below and visit Pechorin’s Journal for a much more useful analysis of Part 2. And, take my advice, do not ever, ever read books in bite-sized pieces from Daily Lit or on your phone, because it’s impossible to get a sense of the bigger picture when you read a book that way.

Update July 22nd

Chapters 5, 6 &7

In Chapter V we discover that Sancho Panza’s wife Teresa shares with Sheridan’s Mrs Malaprop a habit of mangling her words, and so I wonder whether Cervante’s use of it as a comic device is the first instance of it in literature? I also discovered this delicious expression for something that is a waste of time: preaching in the desert and hammering cold iron. It’s used to describe the efforts of Don Quixote’s niece and housekeeper to prevent him from taking off on chivalric adventures again. I also like the analogy of the pyramid to describe lineage and the importance attached to birth:

lineages in the world… can be reduced to four sorts, which are these: those that had humble beginnings, and went on spreading and extending themselves until they attained surpassing greatness; those that had great beginnings and maintained them, and still maintain and uphold the greatness of their origin; those, again, that from a great beginning have ended in a point like a pyramid, having reduced and lessened their original greatness till it has come to nought, like the point of a pyramid, which, relatively to its base or foundation, is nothing; and then there are those–and it is they that are the most numerous–that have had neither an illustrious beginning nor a remarkable mid-course, and so will have an end without a name, like an ordinary plebeian line. (Ch 6)

Cervantes dismisses most of the ancients has having a point like a pyramid: all the Pharaohs and Ptolemies of Egypt, the Caesars of Rome, and the whole herd … of countless princes, monarchs, lords, Medes, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and barbarians, and no doubt we of the 21st century could add a few more today…

Sancho has a go at getting Don Quixote to pay him regular wages instead of promises to award him an estate, but alas, Don Q’s research doesn’t include anything about payments to squires:

I only know that they all served on reward, and that when they least expected it, if good luck attended their masters, they found themselves recompensed with an island or something equivalent to it, or at the least they were left with a title and lordship. (Ch 7)

Samson Carrasco (who thinks he’s a great wit) then comes in to egg on Don Quixote – who taunts Sancho Panza into accompanying him again because now (he thinks) he could choose Carrasco as an alternative squire – and so they resolve their differences and set off again for El Toboso, to get Dulcinea’s blessing. There follows the usual banter between them as Sancho tries once more to relieve Don Q of his illusions about her, with the usual result.

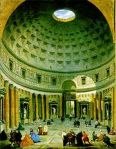

In discussing fame, and the getting thereof, Don Quixote tells an anecdote about the Rotunda of Rome, known to us as the Pantheon.

It is in the form of a half orange, of enormous dimensions, and well lighted, though no light penetrates it save that which is admitted by a window, or rather round skylight, at the top; and it was from this that the emperor examined the building. A Roman gentleman stood by his side and explained to him the skilful construction and ingenuity of the vast fabric and its wonderful architecture, and when they had left the skylight he said to the emperor, ‘A thousand times, your Sacred Majesty, the impulse came upon me to seize your Majesty in my arms and fling myself down from yonder skylight, so as to leave behind me in the world a name that would last for ever.’ ‘I am thankful to you for not carrying such an evil thought into effect,’ said the emperor, ‘and I shall give you no opportunity in future of again putting your loyalty to the test; and I therefore forbid you ever to speak to me or to be where I am; and he followed up these words by bestowing a liberal bounty upon him.

Don Quixote believes that notable deeds bring fame (and it is to delusions of fame like this that we owe the death of John Lennon and others), to which Sancho responds by suggesting that fame as a saint might be preferable, again to no avail. Commanded to find Dulcinea’s palace in El Toboso, Sancho manages to convince his master that they are built there in alleys and persuades him to hide himself outside the town so that he doesn’t discover the truth of Sancho’s previous fibs about Dulcinea. (Chapter 9) Sancho idles about for the day until he sees three village girls and whisks back to tell Don Q that his lady love is on her way. This time the fantasy is reversed, for Sancho pretends that they are suitably bedecked in jewels and other fineries – which of course Don Q cannot see. The lass named as the object of his affection gives him short thrift, but takes a tumble. Don Q helps her out, reels from the smell of garlic on her breath and she takes off, leaving Don Q to curse the ‘enchanters’ who prevent him seeing her ‘in her true guise’. While Don Q berates himself for causing this enchantment, Sancho rejoices to see that his ruse has worked, and the pair set off for a festival at Saragossa. (Ch 10 & 11)

Next they meet players of Angulo el Malo’s company who are in costume for the festival and one of them, horsing about, pretends to joust with Don Quixote. In the ensuing fracas, the mischief-maker takes off with Dapple (Sancho’s mule) – which (despite Sancho’s lack of enthusiasm) leads of course to yet another quest – to retrieve the mule. The players are roused to defence by Don Q’s shouts and threatening demeanour, but the mule is restored to its rightful owner and they go on their way.

There follows an interlude recalling how they had previously met with the Knight of the Grove with whom Don Quixote shared unrequited love, and how they passed the night in storytelling while their squires did the same, although they engaged in some acrimonious comparisons as to their respective rewards for their labours. (Ch 13) The Knight of the Grove told of his passion for Casildea and the quests he had undertaken for her – revealing at the end that since he had vanquished Don Quixote, he could claim all Don Q’s exploits as his own. Don Q was outraged and they agreed to a duel in the morning, much to Sancho’s dismay for it transpired that he was expected to duel likewise with the Knight squire. (Ch 14) (It took no great powers of prediction to anticipate that the troublesome rival was the rascally Samson Carrasco – there was a hint earlier ( in Ch 7, I think) and it was easy to see what was coming: the squire turned out to be Tom Cecial, Sancho’s neighbour and a gossip). Alas, Sancho’s wits were also turned by now, and so both he and his master became convinced that enchantment prevented them from seeing the Knight and his squire in their chivalric role. When, however, Cecial and Carrasco witness the fight with the players of Angulo el Malo’s company, they take themselves off home, leaving Don Q well-satisfied with his latest victory. (Ch 15)

29.7.09 Chapter 16

Ch 16 introduces the ‘man in green’ which reminded me straight away of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. I’m very fond of this 14th century tale, which I discovered at university, and now read, in abridged form, to my year 5 & 6 students. (I use the Michael Morpurgo version illustrated by Michael Foreman). Cervantes’ green man (Don Diego de Miranda) seems only to have green vestments, not a green body and hair, but there’s all kinds of ancient symbolism associated with the colour, which I should look up. However, it’s late at night and I’m too tired to dig out my copy of Landscape and Memory by Michael Schama – which is where I think I read about it. Feel free to correct me if I’m wrong about that, o reader!

(If any reader is still sticking with me, on this very, very long blog post, that is. It’s over 7000 words long now, and we’ve still got a long way to go, and really, dear reader, you’d be much better off reading DQ itself than these ramblings. I’m just writing here to keep track of things because I’m reading other things as well and only coming back spasmodically to deal with DQ – out of sheer determination to finish it.)

Anyway, Don Diego is a very saintly man, but he has one major flaw as far as I am concerned and that is that he would rather his son studied law than the poetry of Virgil and Homer – and I was pleased to see that Don Quixote sets him straight about that! By now, Sancho has figured out that he can explain any misadventures (such as using DQ’s helmet as a container for curds) by blaming enchantment for it, but Don Diego is under no such delusion and both he and Sancho retreat as far as they can when DQ decides to take on a couple of lions which are en route to the court as a present for the King. Fortunately for all concerned the lions are a bit sleepy, and so Quixote is ‘victorious’ and decides to take on a new name, replacing ‘Knight of the Rueful Countenance’ with ‘Knight of the Lions’. He journeys on to the home of Don Diego, where his nonplussed family take no time at all to come to the conclusion that he is ‘a madman full of streaks, full of lucid intervals’ (Ch 18). It seems highly unlikely that Don Lorenzo, (Don Diego’s son) will take up DQ’s advice to give up poetry and take up knight-errantry, but who knows? Cervantes obviously has more adventures in store…

In Chapter 19 the travellers fall in with some peasants and students on their way to the wedding of Quiteria to the wealthy Camacho. Don Quixote takes it upon himself to ‘help out’ the despairing Basilio who also loves Quiteria. There is poetry and song, and plenty of food for greedy Sancho, but the wedding when it happens is between Basilio and Quiteria because Basilio fakes his suicide, and demands that Quiteria marry him before he dies. DQ supports this idea, and the lovely Quiteria seems only too delighted when the dying bridegroom leaps to his feet in triumph at having won his fair lady. Camacho gets over this turn of events remarkably quickly too. The only one unhappy is Sancho, because they leave the feast and set off again. (I have stopped feeling sorry for him because he’s becoming quite cunning.)

I was amused by the cousin who had a thriving business selling liveries to all and sundry, using burlesques of Ovid and Virgil to impress, which made for pleasant conversation as they made their way to the cave of Montesinos. Don Quixote has himself lowered into the depths, and is retrieved almost in a trance over its wonders. He claims to have seen a castle guarded by the old man Montesinos himself – who saluted his exploits and told him of Durandarte, enchanted by Merlin and held on a marble tomb below. Down there with him is an assortment of maidens and the lady Belerma while the duenna Ruidera and her daughters have been transformed into the Lakes of Ruidera in La Mancha, above. He sees Dulcinea, not to mention Lancelot’s Guinevere, Naturally, it falls to Don Quixote to release everyone from this enchantment, without any suspicions about being asked for money while down there…

Then follows a digression with a fortune-telling ape and a puppet-master called Master Pedro, and Sancho takes the opportunity to ask the diviner to explain the mystery of the Cave of Montesinos – for he doesn’t believe a word of DQ’s story. Pedro puts on a show first, which Don Quixote ruins when he takes a fit and tries to kill all the Moors (which are really only pasteboard puppets) necessitating the payment of substantial compensation. (I’m not sure how it is that DQ has so much money on him after all his adventures, but he seems to have plenty.)

It is at this point (Chapter 27) that a character is resurrected from Part 1, i.e. Master Pedro is revealed as Gines de Pasamonte whom, with other galley slaves, Don Quixote set free in the Sierra Morena: a kindness for which he afterwards got poor thanks and worse payment. He was the one who stole Dapple from Sancho Panza, and that was why he knew so much about them. A squabble ensues, and the pair take flight, the reader still none the wiser about the mystery of the Cave of Montesinos.

7.9.09 – back after a bit of a break.

No, I haven’t given up, I’ve just been busy reading Robbery Under Arms for the Classics Reading Challenge. I have 140 Daily Lit episodes to go and I’m going to press on to the bitter end!

It seems to me that by Chapter 29 Cervantes has run out of steam a bit too. Don Q and Sancho manage to steer a boat into the wheels of a river mill because there is a person to be rescued from within ‘the castle’ but in barely a paragraph they agree to cough up 50 reals for the damage and are on their way again. On the other hand it takes many a long paragraph for the pair to get into the duchess’ castle (a real one, at last!) and sort out by whom Dapple the ass may be fed. It takes almost an entire chapter for Don Q to respond to a perceived insult and nearly as long for their beards to be washed by some cheeky serving wenches. I do rather like Sancho’s simple explanation for his continued service of a madman:

If I were wise I should have left my master long ago; but this was my fate, this was my bad luck; I can’t help it, I must follow him; we’re from the same village, I’ve eaten his bread, I’m fond of him, I’m grateful, he gave me his ass-colts, and above all I’m faithful; so it’s quite impossible for anything to separate us, except the pickaxe and shovel. (Chapter 33)

but I’m looking for a wind-up now, a resolution, some sort of finale, and the two paragraphs of proverbs isn’t helping to maintain my interest. I’m sick of the sadistic wit of Cervantes’ characters who think it’s funny to delude Don Quixote and now also poor Sancho, who thinks the Duchess is going to give him an island to govern and worse still, has been persuaded to believe that Dulcinea really has been enchanted. Quite why it becomes Sancho’s place to perform a penance of self-flagellation in order to un-enchant Dulcinea I do not know…

The protracted mockery by Trifaldin of the White Beard and the Distressed Duenna is just more of the same, and apart from some funny word play (veracious/voracious) it seems to be not unlike those awful American sitcoms of the 1960s where the so-called comedy consisted of slapstick and ‘roasting’ each other. I have never found this kind of humour funny, preferring more sophisticated British satire so I’m none too thrilled to see in Chapter 52 that the Duke and Duchess plan more of this ‘droll’ joke. It’s time for bed…

13.9.09

Cervantes makes a point of reminding his readers that Don Quixote’s counsels to Sancho – who is about to take up governorship of his island – are sound common sense, for Don Q only talks nonsense about chivalry, so I think he means it seriously when he says “Eat not garlic nor onions, lest they find out thy boorish origin by the smell” (Ch 43). I find this curious, for to me, these flavourful aromas are infinitely more sophisticated than the smell of bland foods. In the 70s, Australians were often quite rude to Mediterranean migrants who brought garlic in their lunches, but those days are thankfully long gone.

Chapter 44 makes a curious reference to Cide Hamete who wrote the ‘true history of this history’ and his translator who strayed from the original as a kind of protest. It appears to be a kind of justification for the episodic nature of the adventures in Part 2, but I don’t understand why Cervantes appears to be pretending that his tale is based on some other source. It might be some kind of post-modern trick today, but in a story written so long ago, it seems to have no point….

Anyway, Sancho is despatched by their tormentors to a village called Barataria that he is supposed to believe is an island, but his suspicions are roused when he recognises the majordomo as the one who had pretended to be the ‘Distressed One’ i.e. ‘Countess Trifaldi’. Reassured by Don Q he sets off on his way, and the reader is cautioned that she will find the next section most droll.

Let worthy Sancho go in peace, and good luck to him, Gentle Reader; and look out for two bushels of laughter, which the account of how he behaved himself in office will give thee. In the meantime turn thy attention to what happened his master the same night, and if thou dost not laugh thereat, at any rate thou wilt stretch thy mouth with a grin; for Don Quixote’s adventures must be honoured either with wonder or with laughter. (Chapter 44)

Well, I hoped so…. but was quickly disillusioned. What follows is yet another young lady (Altisidora) wooing Don Q to make a fool of him, a prank which ends up with him being quite badly hurt and laid up for eight days. He is then visited by Senora Rodriguez, a needlewoman with a tale of woe which requires his intervention, which is interrupted by two men who attack them both and then mysteriously depart. Don Quixote is about to depart in search of a new quest, when Dona Rodriguez comes back in tears over her afflictions and he decides to help her out. (Without Sancho Panza by his side, oh dear.) They set up a duel to avenge her wrongs…

Not content with this they next send a page to tease Sancho’s wife Teresa so that she acts on her pretensions in the village and makes a fool of herself too. Her letters are read out at court to the amusement of all and they look forward to her arrival with glee.

The good sense of Sancho, meanwhile, enables him to acquit himself well as governor when required to sit in judgement on various cases, and he makes short work of a ‘doctor’ who would in the guise of protecting him from harm removes all the food from his plate. He despatches rogues and mendicants with alacrity and earns the admiration of the populace with his proclamations to reduce prices, and make trade fairer for the poor. But the plan is to bring his government to an end, and before long he is set upon in the night, so much so that even his assailants are concerned that they may have gone too far. He ruefully departs on Dapple for he would rather live a simple life in freedom:

‘I’d as soon turn Turk as stay any longer. Those jokes won’t pass a second time. By God I’d as soon remain in this government, or take another, even if it was offered me between two plates, as fly to heaven without wings.’ (Chapter 53).

On his way back to Don Quixote Sancho runs into one his fellow villagers, Ricote, who is returning from a pilgrimage. Sancho is kindly made to realise that he has been gulled, islands being out in the sea, and no one in their right mind ever likely to make him governor of one. Disillusioned, he falls into a pit in the night, from which he is rescued by Don Q who is out practising for his duel. The duke and duchess are well-pleased with their ruses, and next set up the lackey Tosilos so that no real harm is done in the duel. He, taking the place of the man who had wronged Dona Rodriguez’s daughter, falls in love with her, and there is much indignation when his commoner status is revealed, but she says she’d ‘rather be the lawful wife of a lacquey than the cheated mistress of a gentleman; though he who played me false is nothing of the kind’.

This constant confusion of identities, so amusing in Shakespeare’s plays, is rather wearying in Don Quixote, and I was as relieved as Don Q and Sancho were when finally they departed the castle. Nearing the end (at last! at last!) I wonder how this tale will be resolved…

Chapter 59 offers hope. They are in an inn, and Don Quixote overhears a conversation between Don Juan and Don Jeronimo, who are discussing reading ‘another chapter of the Second Part of ‘Don Quixote of La Mancha’. (This is rather post-modern, eh?) The one says to the other:

“Why would you have us read that absurd stuff, Don Juan, when it is impossible for anyone who has read the First Part of the history of ‘Don Quixote of La Mancha’ to take any pleasure in reading this Second Part?”

“For all that,” said he who was addressed as Don Juan, “we shall do well to read it, for there is no book so bad but it has something good in it. What displeases me most in it is that it represents Don Quixote as now cured of his love for Dulcinea del Toboso.” (Chapter 59)

Don Juan and Don Jeronimo amazed to see the medley he made of his good sense and his craziness convince themselves that the Don Quixote and Sancho of the second part of the history are not those before them. Don Q and Sancho for their part are indignant about Cide Hamete misrepresentations and set out for Barcelona, Don Q beseeching the reluctant Sancho to resume the whippings so that Dulcinea can be restored from her enchantment. They are then set upon by robbers under the leadership of one Roque Guinart, a sort of Robin Hood fellow, who then travels with them.

As the book nears its conclusion, there follows a hasty sequence of events, one after the other, some tying up loose ends and others of no apparent relevance to the plot. (What plot?)

In Barcelona ‘Don Quixote’s host was one Don Antonio Moreno by name, a gentleman of wealth and intelligence, and very fond of diverting himself in any fair and good-natured way; and having Don Quixote in his house he set about devising modes of making him exhibit his mad points in some harmless fashion; for jests that give pain are no jests, and no sport is worth anything if it hurts another’. (Chapter 62) Cervantes’ statement here seems a bit odd to me, at the near end of a great catalogues of ‘jokes’ many of which have hurt both body and soul. Don Moreno makes fun of Don Q with an ‘enchanted ‘ bust which talks to him (though in reality the speaker is Don Moreno’s nephew, concealed beneath the table). There follows a curious episode between Don Quixote and some printers, a discussion about the merits of translators and copyright issues, and Don Q’s discovery of the manuscript of his own history. Then they board a galley and Ricote’s daughter Ana Felix is restored to him, there is an encounter with the Knight of the White Moon who vanquishes Don Q in a joust and requires of him that he returns home. He turns out to be the bachelor Samson Carrasco from Don Quixote’s village who, in a previous guise as the Knight of the Mirrors, had tried and failed to get him home so that he might rest and be cured of his madness.

So they set off, but the wench Altisidora hasn’t finished with him yet, for at the court of the duke and duchess yet another ruse takes place where Sancho is expected to submit to a beating in order to bring her ‘back to life’. This makes Don Quixote renew his pleas for Sancho to resume his whippings to relieve Dulcinea of her enchantment, but Sancho, (wisely) is unconvinced. As they take their rest, Cide Hamete makes his appearance to:

record and relate what it was that induced the duke and duchess to get up the elaborate plot that has been described. The bachelor Samson Carrasco, he says, not forgetting how he as the Knight of the Mirrors had been vanquished and overthrown by Don Quixote, which defeat and overthrow upset all his plans, resolved to try his hand again, hoping for better luck than he had before; and so, having learned where Don Quixote was from the page who brought the letter and present to Sancho’s wife, Teresa Panza, he got himself new armour and another horse, and put a white moon upon his shield, and to carry his arms he had a mule led by a peasant, not by Tom Cecial his former squire for fear he should be recognised by Sancho or Don Quixote.

He came to the duke’s castle, and the duke informed him of the road and route Don Quixote had taken with the intention of being present at the jousts at Saragossa. He told him, too, of the jokes he had practised upon him, and of the device for the disenchantment of Dulcinea at the expense of Sancho’s backside; and finally he gave him an account of the trick Sancho had played upon his master, making him believe that Dulcinea was enchanted and turned into a country wench; and of how the duchess, his wife, had persuaded Sancho that it was he himself who was deceived, inasmuch as Dulcinea was really enchanted; at which the bachelor laughed not a little, and marvelled as well at the sharpness and simplicity of Sancho as at the length to which Don Quixote’s madness went. The duke begged of him if he found him (whether he overcame him or not) to return that way and let him know the result.

This the bachelor did; he set out in quest of Don Quixote, and not finding him at Saragossa, he went on, and how he fared has been already told. He returned to the duke’s castle and told him all, what the conditions of the combat were, and how Don Quixote was now, like a loyal knight-errant, returning to keep his promise of retiring to his village for a year, by which time, said the bachelor, he might perhaps be cured of his madness; for that was the object that had led him to adopt these disguises, as it was a sad thing for a gentleman of such good parts as Don Quixote to be a madman. And so he took his leave of the duke, and went home to his village to wait there for Don Quixote, who was coming after him. Thereupon the duke seized the opportunity of practising this mystification upon him; so much did he enjoy everything connected with Sancho and Don Quixote.

He had the roads about the castle far and near, everywhere he thought Don Quixote was likely to pass on his return, occupied by large numbers of his servants on foot and on horseback, who were to bring him to the castle, by fair means or foul, if they met him. They did meet him, and sent word to the duke, who, having already settled what was to be done, as soon as he heard of his arrival, ordered the torches and lamps in the court to be lit and Altisidora to be placed on the catafalque with all the pomp and ceremony that has been described, the whole affair being so well arranged and acted that it differed but little from reality. And Cide Hamete says, moreover, that for his part he considers the concocters of the joke as crazy as the victims of it, and that the duke and duchess were not two fingers’ breadth removed from being something like fools themselves when they took such pains to make game of a pair of fools.

These clarifications made, Cervantes takes his hero home, and bumps him off! He never gets over his disappointment that Dulcinea remains enchanted, and remains grieved that he was vanquished in his attempts. On his death bed, he recants his fantasies, recognising that all his woes have come about through reading books fo chivalry:

My reason is now free and clear, rid of the dark shadows of ignorance that my unhappy constant study of those detestable books of chivalry cast over it. Now I see through their absurdities and deceptions, and it only grieves me that this destruction of my illusions has come so late that it leaves me no time to make some amends by reading other books that might be a light to my soul.

He leaves a Will that is generous to all, especially Sancho, with a caveat that his niece is not to marry anyone who reads books of chivalry.

And I, at last, have reached the end! I admit to feeling disappointed: reading this ancient story became a quest in itself, as insane as any of Don Q’s. I am sure that in recording my banal conclusions and confusions I have done no more than waste my own time, as well as anyone persistent enough to read this blog post to the end. (It’s over 11,000 words long.) I don’t doubt what Wikipedia says, that Don Quixote is the most influential work of literature to emerge from the Spanish Golden Age and the entire Spanish literary canon. As a founding work of modern Western literature, it regularly appears high on lists of the greatest works of fiction ever published [3] but I have mostly failed to identify the reasons for its longevity on these lists.

Ah well, so be it.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Quixote

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lothario

[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_quixote

Author: Cervantes

Title: Don Quixote

Publisher: Daily Lit

Lisa,

You have made it further into the book than my last attempt! Now I know I will have to try it once again.

Helen

LikeLike

By: Helen on August 3, 2009

at 7:52 am

I would love to know how many pages long it is as a regular book rather than instalments from Daily Lit!

I am hoping that as I plod on I will begin to see the patterns and themes that have made it such an influential work, but right now, it seems I am just wading through a series of plot events…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 3, 2009

at 2:01 pm

This must be the world’s longest blog post! You did very well to write such an erudite summary and critique of the book, including your personal experience in reading it. I am sure this is a post I will return to when I start reading this book in August.

LikeLike

By: Tom Cunliffe on May 2, 2010

at 4:53 pm

*chuckle* Tom, you’d be much better off reading the Spark notes!

Except my videos are rather good, aren’t they?!

Oh

Well, they were. When I clicked on them, the first one has vanished, and the second one notes that it is ‘stolen’. I’ve had to update the post to reflect this, as you will see above.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on May 2, 2010

at 5:28 pm

What a shame they’re gone – I would have liked to see them. This one will have to do for now.

LikeLike

By: Tom Cunliffe on May 3, 2010

at 9:54 pm

Oh dear, I didn’t mean to insert it into your post! Sorry about that.

LikeLike

By: Tom Cunliffe on May 3, 2010

at 9:55 pm

That’s ok, Tom, it’s a lovely clip. I’ve just edited your comment above to swap the link for the actual video:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on May 3, 2010

at 10:18 pm

[…] Tale (Lahni) 4. Fingersmith (Esther) 5. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Carrie) 6. Don Quixote (Lisa Hill) 7. Becky (Tarzan of the Apes) 8. One Hundred Years of Solitude 9. A Room With A View (lisajo) 10. […]

LikeLike

By: September/October 2009 Reviews : 1% Well-Read Challenge on February 5, 2011

at 3:52 pm

Thanks for sharing your journey through Don Quixote. As part of my Don Quixote reading challenge for 2013 on my blog, Artuccino. I’ve reached Chapter XXVI (Page 204) of Edith Grossman’s translation. I hope it’s OK to add my thoughts on the book so far, to your blog post: So far, I think it’s a “silly” story. I should also add that I think Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is silly too. I’m not regretful that my serious reading choice for 2013 is Don Quixote. (Strange I refer to a “silly” story, a comedic story, as a serious read. It’s serious for me because it’s a struggle to read it.) It’s a book I’ve had on my list for a long time, it’s on my classics list because I want to expand my reading horizons beyond the easy to read, entertainers. A couple of years ago I did an evening class on the subject of “The Art of Reading” and it was at that time I decided to choose a classic from the enormous list of “important” books. A new translation of Don Quixote had just been published, the Edith Grossman translation, and there was a lot of buzz about it. So it became my choice. The first problem was its physical size, it was the size of a house brick not practical to lug it around so it went onto the bookshelf for several years. Now, years later the situation has changed, the reading world has changed, I’m an avid follower of book bloggers who inspire me to once again tread the “classics” path, so with the help of an eBook reader (Kindle) and an audiobook (Audible.com) I’ve got no excuse. So one chapter a day, until I’ve finished will mean I have experienced a story considered “important”. Along the way I may discover WHY it’s “important” and at the very least my reading muscle will get stronger.

LikeLike

By: Diane Challenor (@CynthiaBlue44) on February 28, 2013

at 5:00 pm

Hello Cynthia, what a wonderful story you have shared:)

I think it’s wonderful when readers decide to take the plunge into books beyond the easy-to-read entertainers, and what I love about the new cyber world of books is that there are always people around – with different levels of experience and expertise to share the journey with.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 28, 2013

at 5:18 pm

[…] post is going to be one of those ‘written-as-I-read-it’ ones (like Voss, Don Quixote and Tale of the Tub) because I want to record what I find interesting as I read it and I don’t […]

LikeLike

By: A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads, by Anthony Reid (and thank you to Kingston Library) | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 9, 2015

at 12:00 pm

[…] essay I want to discuss here is ‘Partial Magic in the Quixote’ because I have recorded my adventures with Don Quixote here on this blog (and note that I do not presume to call my blundering thoughts a […]

LikeLike

By: ‘Partial Magic in the Quixote’, from Labyrinths, by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by James E. Irby | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on October 17, 2016

at 11:35 am

[…] depicts Don Quixote as mad and a butt of humour. [Well, at least I got that part right when I read it myself.] Don Juan, […]

LikeLike

By: Spanish Literature, a Very Short Introduction, by Jo Labanyi | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on October 15, 2017

at 7:34 pm

[…] Don Quixote (1605/15) by Miguel de Cervantes (see my rambling thoughts here) […]

LikeLike

By: Literary Wonderlands, edited by Laura Miller #BookReview | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on September 23, 2018

at 1:52 pm

I’m very weary of this book too Lisa. I’ve been reading this a chapter a day since the beginning of the year and have failed to feel very amused or entertained. I’m finding DQ’s madness tedious and repetitive and Sancho’s naivety annoying. What is the point of it all?

LikeLike

By: Brona on March 4, 2019

at 7:16 pm

I hear you Brona! I admit to feeling only a perverse sense of pride at finishing it, but otherwise have no fond memories of it at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on March 4, 2019

at 9:19 pm

“regularly appears high on lists of the greatest works of fiction ever published…. but I have mostly failed to identify the reasons for its longevity on these lists”

Tell you why, am recently enlightened, I hope!

Cervantes tilt at us

Cervantes’ Quijote tilts at truth duelling delusion, announces the universal timeless “modern”

Tilts at reality, humanity’s perennial challenge of sifting fact from fancy

Ironically his oppressive Spanish foe provoked the old man’s ingenious method, touching a universal nerve

Unlikely, unfinished work, a rough and ready “modern” literary gold mine, allegorical, allusive, untidy, but speaking to everyone

At the c1600 CE end Mediaeval conception of the journey to the “modern”, to conscious open eyed scrutiny of natural world

Recalls Homer at dawn Archaic Greece? Wagner’s mid 19th C Der Ring?

LikeLike

By: william s etheridge on June 18, 2023

at 6:29 pm

Thanks, William… it’s a long time since I read (or rather, I should say, tried to read) CQ, but I relate to what you describe as its untidiness.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on June 19, 2023

at 8:48 am

Lisa, v interesting book. I started about 5y ago, dived in, read parts and people’s views. Seemed to matter, v odd writing for c1600. Crazy. Revisiting lately it all made sense. I run a lot, keep fit, and its funny how then thoughts can suddenly fall into place. Key issues are he was old and getting it off his chest [like Dante was with his DC], fed up with Spain, but he couldn’t say this out loud then, so used a fairy story. Ingenious. Tilted at the delusion which held oppressive old Spain together, but hence at all self serving delusion. Which of course is universal, try Trump and P today. Atb with it. W

LikeLike

By: wse999 on June 19, 2023

at 9:01 am

I expect you’re right, and DQ has a hallowed place in world lit. But I write here from the PoV of the bemused ordinary reader, and while sometimes I’m more than willing to make an effort to go further (e.g. as I have with James Joyce) there are other books where I think, ok, I don’t get it, and I just move on. DQ is one of those!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on June 19, 2023

at 11:34 am

Haha! Understand. For me the penny dropped. Weird. The eternal battle between fact and fancy. I just read his preface to 1613 Exemplary Novels, then aged 66 and v interesting. He knew he was saying something that mattered, self confident. PS: William Egginton is vg on MC.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: wse999 on June 19, 2023

at 11:07 pm