Voss was Patrick White’s fifth novel and is the book that won the inaugural Miles Franklin Award in 1957. Prior to that the writer who would become Australia’s only Nobel Prize Laureate had been dismissed in Australia, as indeed he so often is today. Where else but Australia could there be a website so offensively titled as the ABC’s Why Bother with Patrick White?

Update 2/12/22: I see that the site has been removed, and good riddance. You’ll have to take my word for it about what follows.

There is a curious ambivalence about this site, presumably set up to explain White and his works yet careful to add demurrers – as if to commit the un-egalitarian sin of praising White is to risk the charge of being ‘un-Australian’. To read through the Opinion pages is to feel an increasing sense of dismay when there are comments like this:

White’s critique of Australian ordinariness is no longer especially vital or useful, and that his reputation is as Australia’s genius loci means it is more important to criticise than to join him. He is doomed to be increasingly neglected, or, at any rate, celebrated only in lip-service.(Simon During)

Ludwig Leichhardt

Yet it’s included in 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die and the summary of Voss suggests an enticing story. It is a fictionalised account of the life of the explorer Ludwig Leichardt, and it is salutary to remember that despite the fuss sometimes made about it today, fictionalising actual events is nothing new. What was distinctive about Voss is that the novel is an example of High Modernism – which according to Norton celebrates ‘personal and textual inwardness, complexity, and difficulties’ and this movement was out-of-date by the end of the 1920s. Alternatively, says Wikipedia, High Modernism is characterised by the ‘Great Divide’ i.e. a clear distinction between capital-A Art and mass culture, and it places itself firmly on the side of Art and in opposition to popular or mass culture. That sounds more like Patrick White!

It’s not prose that flows, but rather that draws attention to itself with striking metaphor. When White writes The darkness was becoming furious (p89, Vintage Classics Edition) – in these five words one can imagine a spiteful wind springing up and hurling little eddies of leaves onto the ankles of Voss and Laura as they walk alone in the garden. But there’s also all the baggage of Night itself, with social meanings, pregnant with gossip and innuendo and anxiety about the reputation of women and girls. There’s also this, about Voss’s intrusion into the Bonner’s carriage and his awkward departure: All this queerness was naturally discussed as the carriage crunched onward, and the German, walking into the sunset, was burnt up. (p73) Clever it is, but it can sometimes be quite bewildering, even if you think you know what White is doing…

I have blogged before (see Modernism – Hooray for Wikipedia) about how my reading of Voss coincided with reading Margaret Olley, Far From a Still Life, and how I discovered Wikipedia’s article about Modernism in painting. From this and other reading I grasped the idea that (in art) it means to exaggerate some aspect of a subject and not necessarily to be obliged to represent reality. So, in William Dobell’s portrait of Joshua Smith, the exaggeratedly long neck and large ears; in Impressionism the exaggeration of light and movement; and in Olley’s work, exaggeration of colour, and perspective. This exaggeration can also be seen in White’s portraits….

Minor characters are deftly rendered:

His Excellency the Governor wished Mr Voss and the expedition God-speed and a safe return, the Colonel said, with the littlest assistance from his fleshless face, which was of a rich purple where the hair allowed it to appear. And he clasped the German’s hand in a gloveful of bones. (p113)

Sometimes with White’s spiteful wit:

The numerous grave and important people who were surrounding the Colonel lent weight to his appropriate words. There were, for instance, at least three members of the Legislative Council, a Bishop, a Judge, officers in the Army, besides patrons of the expedition, and citizens whose wealth had begun to make them acceptable, in spite of their unfortunate past and persistent clumsiness with knife and fork. (p113)

He also refers to the Palfreymans as being of the doormat class (p350) – and Laura’s wardrobe at the Bonner’s is ‘not a very good piece of furniture, but Mrs Bonner truly did love her niece, in whose room she had put it. (p374) Such exquisite social commentary!

His scorn for mass culture intrudes in unexpected places. Sanderson, a pastoralist who escorts Voss from The Osprey into the bush, is an ascetic who left Belgravia to ‘mortify himself’ in Australia. Despite himself he is rich, and owner of a vast amount of land, but he leads a restrained life, except for his predeliction for books.

His scorn for mass culture intrudes in unexpected places. Sanderson, a pastoralist who escorts Voss from The Osprey into the bush, is an ascetic who left Belgravia to ‘mortify himself’ in Australia. Despite himself he is rich, and owner of a vast amount of land, but he leads a restrained life, except for his predeliction for books.

He did live most simply, together with his modest wife. They were seldom idle, unless the reading of books, after the candles were lit, be considered idleness. This was the one thing people held against Sanderson, and it certainly did seem vain and peculiar. They had whole rows of books, bound in leather, and were for ever devouring them. They would pick out passages for each other as if they had been titbits of tender meat, and afterwards shine with almost physical pleasure. Beyond this, there was nothing to which a man might take exception. (p126)

‘The Last Days of Leichhardt’ by Albert Tucker, 1964

It is near impossible to read Voss without having to pause to think about these self-conscious images. Definitely not bedtime reading! I couldn’t just keep turning the pages when I read, horrifed, the scene where Voss’s letter to Laura is lost. There were other poignant losses: the expedition’s cattle; the navigation equipment; Rose Portion – who had only a meagre slice of life; and then Mercy’s place in society; the expedition itself – but this loss when Dugald abandons his mission bears so many meanings, it’s worth quoting in full:

‘You will go straight to Jildra,’ said the German, but making it a generous command.

‘Orright, Jildra,’ laughed the old man.

‘You will not loiter, and waste time.’

But the old man could only laugh, because time did not exist. (p218, my underlining)

Was this the first time in literature that a writer has understood with such sensitivity the Aboriginal world view, their ties of kinship and the vulnerability of their way of life? Here is Dugald en route, meeting up with his people and trying to explain his burden:

These papers contain the thoughts of which the whites wished to be rid, explained the traveller, by inspiration: the sad thoughts, the bad, the thoughts that were too heavy, or in any way hurtful. These came out through the white man’s writing stick, down upon paper, and were sent away.

Away, away, the crowd began to menace and call…

With the solemnity of one who has interpreted a mystery, he tore them into little pieces…

The women were screaming, and escaping from the white man’s bad thoughts. Some of the men were laughing.

Only Dougal was sad and still, as the pieces of paper fluttered around him and settled on the grass, like a mob of cockatoos.

Then the men took their weapons, and the women their nets, and their dillybags, and children, and they all trooped away to the north where at that season of the year there was much wildlife and a plentiful supply of yams. The old man went with them, of course, because they were his people, and they were going in that direction. They went walking through the good grass, and the present absorbed them utterly. (p220)

In those few short paragraphs White shows the gulf between what Dugald and Voss understood of one another and how there can be no conception of betrayal of trust and no guilt. They were Dugald’s people, and they were going in that direction. The present absorbs them into the landscape which has been theirs for millenia – but this way of life, even then on the edge, is doomed. A loss of unimaginable proportion.

In her letter to Voss, Laura begins to understand:

‘This great country, which we have been presumptuous enough to call ours, and with which I shall be content to grow since the day we buried Rose. For part of me has now gone into it. Do you know that a country does not develop through the prosperity of a few landowners and merchants, but out of the suffering of the humble? (p239)

Amongst Wikipedia’s thematic characteristics of Modernism, I see these in Voss, but there are many, many more:

The Breakdown of Social Norms

- the inclusion of the convict, Judd, in Voss’s party, and his subsequent elevation to leader;

- the servant Rose Portion not only staying on in a middle-class family when pregnant, but also Laura adopting the baby;

- the catastrophic breakdown of Aboriginal social norms, especially in Jackie’s behaviour;

- the collapse of the British class system – it doesn’t work in a penal colony where convicts can transcend the welts on their backs and where the aristocrat at Jildra lives in squalor at the ‘last hospitality civilization would offer them; (p167)

- In Ralph Angus, the compassion for the convict began to struggle with the conventions he had been taught to respect (p292) – the grazier apologises to the convict for Voss’s rudeness;

- the way that traditional morality is abandoned; and

- the questioning about God and religion.

The Sense of Alienation

- Laura’s from society and family;

- Voss’s from society and his homeland and language – he even wants to be alone when the expedition is out in the middle of nowhere;

- Jackie and (at least initially) Dugald from their own people; and

- Judd choosing not to return to ‘civilisation’ for so long

The sense of spiritual loneliness

- Laura prays but not to a kind and loving God; and

- The personification of vast distances and a hostile landscape.

Despairing individual behaviours

- Le Mesurier seems first to will himself to die, and then walks out into the wilderness to accomplish it.

Stylistic features I’ve noticed include:

- The discontinuous narrative, jumping from Laura in Potts Point, Sydney, to Voss in the unknown inland, and back again. It’s more pronounced in later chapters.

- Antiphraxis (ironic figures of speech, words meaning their opposite, like the pieces of paper reduced to being like a mob of cockatoos – meaningless chatter when Voss’s letter is profoundly serious (p220).

- Parataxis – which is what makes me sit up and take special notice – short sentences juxtaposed without any obvious connection, like the spaniel being preferable to children. Children are little animals that begin to think by thinking of themselves. A spaniel is more satisfactory. (p221)

- Figures of speech – including my favourite: In the grey light and first house-sounds, Voss woke and lay with his face against the pillow, whose innocent down was disputing possession of him with the day. (p140) I so often feel like this!

It’s so rich and excitingly complex, I could go on and on about it….There is a rainbow serpent (p281), and biblical references like the flood, but some of the allusions leave me mystified. What is the significance of Judd getting goat’s milk for the fevered Le Mesurier, which gives him diarrhoea, just as Voss predicted? Why does Voss break all the rules of privacy, overcome his conscience and prudence, and read Le Mesurier’s bizarre and incomprehensible poems? (p294) He fears reading about himself, but is compelled to go on – and the poems appear to be the gibberish of a madman, though I bet they’re not. The only one I can make any sense of is the Conclusion in Stanza I which suggests that Le Mesurier thinks that the rock art foretold his ‘mysteries’; that ‘his kingdom was dust’ ‘which paid him homage for a season’ and ‘fevers turned him from Man into God’, (p296). He foresees their doom, becomes afraid their bodies will be eaten and prays that his spirit will live on.

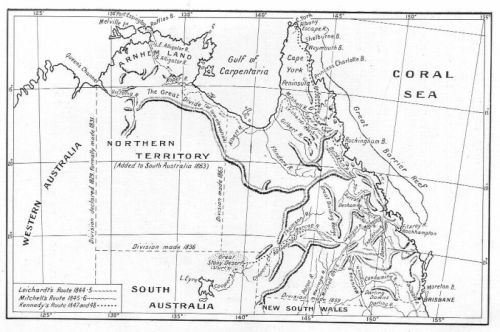

Routes of Leichhardt (1844 and 1845); Mitchell (1845 and 1846); and Kennedy (1847 and 1848).

The landscape almost becomes the plot. After being trapped in a cave due to wet season floodwaters, at last in Chapter 12 the waters recede and the men congratulate themselves and prepare to move on. They move through green ‘parklands’ they imagine have been put there for their benefit, White mocking the arrogance of white men who know nothing about the country they are planning to master. ‘The land was celebrating their important presence with green grass that stroked the horses’ bellies’. (p333) They are exultant, they sing songs of their childhood and youth; they have plenty of game to eat (though they don’t eat much because their stomachs have shrunk) – but ‘into this season of grass, game and songs burst other signs of victorious life’. (p334). An Aboriginal turns up making threatening gestures, but Voss thinks he is a poet and goes forward to meet him. His overtures are rejected, much to his surprise, but he dismisses them patronisingly: ‘It is curious that the primitive mind cannot sense the sympathy emanating from relaxed muscles and a loving heart.’ (p335). The rest of the party doesn’t laugh, and parties of Aborigines begin to follow them. The dog Tinker disappears, and the country, ominously, changes.

Very soon after this, the fat country through which they were passing began to thin out, first into stretches of yellow tussock, then into plains of grey saltbush. which, it was apparent, the rains had not touched. Even the occasional outcrops of quartz failed as jewellery upon the sombre bosom of that earth. (p336)

Turner is the first to panic at the ‘prospect of re-entering the desert’ (p336) and the others felt the same but they pressed on.

So the party entered the approaches to hell, with no sound but that of horses passing through a desert and saltbush grating in the wind. This devilish country, flat at first, soon broke up into winding gullies, not particularly deep, but steep enough to wrench the backs of animals that had to cross them, and to wear the bodies and the nerves of the men by the frantic motion that it involved. There was no avoiding chaos by detour. The gullies had to be crossed, and on the far side there was always another tortuous gully. It was as if the whole landscape jad been thrown up into great earthworks defending the distance. (p336)

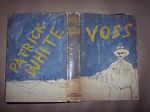

Voss (1957), dust jacket designed by Sidney Nolan

There is a hideous moment when one of the horses stumbles from a ridge and the poor tortured beast, blinded by blight and covered in sores, has to be shot, and no one can shoot the men to put them out of their misery. Turner has boils and bleeding gums, and they are all suffering from scurvy except for Voss who found the cress planted by Palfreyman and ate it. Now when they are weak and in terror of the desert, the presence of the Blacks is threatening (p339) and hope is gone. They sleep with firearms handy. It is as if both climate and landscape conspire to lure them into the desert. It put me in mind of docos of relentless arid distances; of a hatefully hot day on holiday in the Little Desert some years ago; and of those early mariners who believed that if they sailed too far they would fall off the edge of the world. Here in Australia our inland deserts are the edge of the world as we know it, and every now and again some hapless traveller dies out there, as if Nature is determined to remind us to respect the sanctity of the interior. Our 4WDs cling to the eastern seaboard with good reason.

Leichhardt’s compass

Disaster strikes yet again when Palfreyman is speared. Christlike, he takes on the sins of the others, and goes to his death believing in redemption. (p342) Judd fires his gun in retaliation, causing another of the Aborigines to fall down a gully in panic. All this begins when overnight some things are stolen from inside the tent: an axe, a bridle and the remaining compass. It isn’t clear who did this, but the Aborigines are suspected.

An earlier incident at Jildra was unresolved too. Judd, taking an inventory of equipment, says he can’t find the large compass in a box. A search ensues, and it is found in his saddlebags. Only he is surprised, because the others expect him to steal, since he was a convict.

Anyway, they confront the Aborigines, the deaths happen, and the compass is found afterwards, smashed in the dirt – thereby obviating the need to choose which of the two rival parties shall have it when they split up.

Judd – practical, methodical, inventive with tools – can see their fate. ‘I cannot dream dreams no longer. Do you not see our deluded skeletons, Mr Voss?‘ (p340). He is an enigmatic character. Does he want to be Voss’s rival for leadership of the party? Did he take either or both of the compasses – or was it Voss, sleepwalking? Whyever did he choose to go on this expedition, leaving his wife and children, and the success he had made of his life as a ticket-of-leave man? Some sort of expiation for crime??

He has leadership qualities, a foil to Voss. Most of the party chooses to go with him when he finally refuses to go on. It was he who had the foresight to keep one compass dry in his saddlebags at the river crossing, but he resents Voss for the loss of the rest of the equipment. It is a sign of the inversion of social mores when Voss tells Judd that he wants something to keep their navigation instruments dry in the Wet (p292) and Judd (who has spent the day making little oiled bags to keep their medicines dry) retorts that they’re already wet (because they’re in the river after Voss’s orders to raft them across went awry). Voss has the effrontery to rebuke him by saying that Judd would have been better to have kept them from the raft rather than the remnants of flour he was able to save – and Judd nearly loses his temper but admits that he had kept one compass in his saddlebag as well as the flour. Voss sneers that this last remaining compass will be ‘an embarrassment’ if they split into two parties, and it is this compass that is found smashed 100 yards from the camp. (p344)

After the mutiny (p345) when Judd and the others refuse to go on, Voss is left with Le Mesurier who is sick; Harry Robarts, who is simple, and Jackie, the Aboriginal. Voss accuses Judd of cowardice, but Judd repudiates this. ‘It is not cowardice if there is hell before and hell behind, and nothing to choose between them’. (p346) He want to go home – and who would blame him? but Voss sneers that ‘small minds quail before great enterprises‘ and who could disagree with that either?

I am not sure how to label Laura’s ‘presence’ in the last stages of Voss’s journey. She has attended a dance in honour of Belle’s engagement to Mr Radclyffe, danced innocently with him and Willie Pringle (a childhood friend) but not with Dr Badgery, who fancies her, out of loyalty to Voss. In a neat inversion of Jane Austen’s gorgeous young officers visiting Bath, Badbery is a podgy surgeon from a rather tatty visiting ship that is what passes as an appealing addition to society in colonial Sydney. Laura has gone down with a severe fever, and they have cut off her hair. (What does that symbolise? Is it analogous to castration??) Simultaneously, in the desert, she rides alongside Voss, who by now is riddled with sores, as is his horse. ‘Vermin were eating him’ but her words are ‘ointment‘ as well as a balm for his soul. (p363) Is White just showing us Voss’s delusions? If so, they are matched by hers, but how can she have any conception of what he is going through?

Laura, in her fever, offers up Mercy (the child) as a sacrifice, so that Voss may survive. (pp367-374) The Bonners had wanted the child fostered out to the childless Asbolds because the scandal affected her ‘prospects’ and (not knowing she has pledged herself to Voss) they expect her to marry. This wish is thwarted by Mrs Bonner, who during Laura’s illness has grown fond of the child, and wants to be her ‘Gran’. But what is the signifiance of the three pears that go off, and make the Bonner’s house smell? Mr Bonner paid a lot of money for them as a gift for Laura ‘to express affection’ and is ‘rather lonely in the brougham’. (p353) Does he plan to have a dalliance with her?? Mystifying!

The comet which marks the redemption of Voss can be seen across the vast distances encompassed by this novel, from Potts Point to the waterhole where the Blacks have built a shelter for the remnants of the partyand held a corroboree. Jackie has returned as an envoy of the Aborigines to whom he says he belongs. Voss asks where does he belong, if not in the desert, and asks to be friends, but Jackie has forgotten what the word means. (pp364-5) Nevertheless he invites the party to go with the blacks, and they are led along a path cleared of the blinding quartz rocks to this waterhole. But the Aborigines fear the comet, and Jackie thinks that Voss has made it through magic. Le Mesurier goes off by himself to pre-empt them killing him, not knowing that as the comet moves across the sky, they have come to believe that the Great One has ‘burrowed into the soft sky and was sleeping off the first stages of his journey to the earth.’ (p380).  Harry and Voss are too exhausted to bury him, and Harry dies in the night but so oblique was White’s prose (or I am so dim!) that I did not realise this until the Blacks remove the ‘profane body of the white boy’ seven pages later. Laura is there with Voss, sometimes in the form of the black woman who sits vigil. Shorn of her hair and bled with leeches (pp384-6) she is raving about God and Man; while Voss is fed a witchetty grub. These are clever inversions: Laura feeds the leeches; the grub feeds Voss; the Aborigines make jokes and songs about Le Mesurier’s body making white maggots (p389).

Harry and Voss are too exhausted to bury him, and Harry dies in the night but so oblique was White’s prose (or I am so dim!) that I did not realise this until the Blacks remove the ‘profane body of the white boy’ seven pages later. Laura is there with Voss, sometimes in the form of the black woman who sits vigil. Shorn of her hair and bled with leeches (pp384-6) she is raving about God and Man; while Voss is fed a witchetty grub. These are clever inversions: Laura feeds the leeches; the grub feeds Voss; the Aborigines make jokes and songs about Le Mesurier’s body making white maggots (p389).

And Jackie, who has to rid himself of ‘the terrible magic that bound him remorselessly, endlessly to the white man’ (p384) goes into the shelter, stabs Voss in the throat and then hacks his head off. The irony of this gruesome act is that in his ‘increasing but confused manhood’ (p394) he used a metal knife to do the beheading – which is in multiple ways a rejection of his own culture.

Laura recovers and becomes a schoolmistress at a ladies’ academy. Only 26, her fate as an old maid seems set. Mercy is with her, dressed differently to the other girls, who tease her not too unkindly.

A party is held to celebrate the return of a search party looking for Voss. All they found was the ‘very valuable’ button given to Dugald by Boyle as a reward for going on the expedition. Both Aborigines have been questioned: the searchers now know that Dugald left first; that a party of Aborigines who called in at Jildra re-enacted a massacre of horses; and that Jackie’s wits are gone. The fate of the mutineers was not known.

Despite Laura asking him to leave things in peace, Colonel Hebden sets out again. At Jildra he finds that Jackie has been and gone: he spends the rest of his short life as an oddity among his own kind, ‘a legend among the tribes’. (p421) He eventually dies in a thunderstorm as he crosses a swamp (p427) but Col. Hebden never knows this and always hopes to apprehend him. Jackie had, after running away from Voss and the blacks, come across the bodies of Turner and Angus, though not Judd. He had met and told Dugald about the mutiny, but not about the fate of the two men. In yet another irony Col. Hebden comes within a ‘good stone’s throw’ of these bodies when the search party decided to turn back after ‘this most irrational country’ had made him look ‘ridiculous‘. (p421)

White the omniscient narrator reveals the fate of the mutineers: Turner, the grazier, gives up first. He lets go the reins and falls from his horse. Short thereafter Angus, worried he might not die ‘in a manner befitting a gentleman’ has his horse stumble and slides down the ‘infernal pyramid’ – the outcrop of shade which Judd remains determined to reach. (p425).

The last chapter ties up the loose ends. Belle, now middle-aged has another party. Laura, with Mercy in tow, has been to an unveiling ceremony: a statue of Voss has been placed in the Domain (p439). Judd has been found, after living with the Blacks all this time. Laura, somewhat unwillingly, meets him and asks after his family – who are all dead, and his land has been resumed because everyone thought he was dead. He speaks of Voss, although ‘a little twisted’ as a Christian saint, washing the sores of the others (p443). He says also that the spirit of Voss is still in the country – and not just because he cut his initials into the trees.

But he also says that he was there when Voss was speared by the Blacks, and that it was he who closed his eyes. Col. Hebden challenges this change in Judd’s story, but it finally enables Laura to ‘draw a shroud about herself’. Hebden cyncially says to her:

‘Your saint is canonised.’

‘I am content.’

‘On the evidence of a poor madman?’

‘I am content.’

‘Do not tell me any longer that you respect the truth.’

….

‘Whether Judd is an impostor, or a madman, or simply a poor creature who has suffered too much, I am convinced that Voss had in him a little of Christ, like other men. If he was composed of evil along with the good, he struggled with that evil. And failed.’ (p445)

A drunken Englishman, wishing to make sport of Laura and her ‘bastard child’ is silenced:

‘Voss did not die, ‘ Miss Trevelyan replied. ‘He is there still, it is said, in the country, and always will be. His legend will be written down, eventually, by those who have been troubled by it.’ (p448)

And White did so!

Author: Patrick White

TItle: Voss

Publisher: Vintage 1994

ISBN: 9780099324713

Source: personal copy

Availability: Fishpond: Voss

You have written a treatise! I’m afraid I won’t read it properly now. Will save that until my reread of Voss at the end of the year. It’s not so much that I fear spoilers as I know what happens but it’s been so long since I read it that I want to come back to it afresh – I expect my 57 year old self will love it just as my 17 year old self did but with different eyes. When I do reread it I will certainly read what you have written as it seems like you’ve put a lot in here across a range of issues. Good on you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: whisperinggums on June 8, 2009

at 11:33 pm

I believe that Bill and Karen are planning on reading Voss during November for AusReadingMonth and I hope to join them too, so like Sue will save this post for when I finish the book. I attempted a couple of Whites in my late teens and we didn’t gel, so I’m hoping mid-50’s Bron & White get on better!

LikeLike

By: Brona's Books on July 23, 2022

at 1:41 pm

I bet I wouldn’t have got on with him then either, not without the help of an exceptional teacher, and I only ever had one of those and that wasn’t until I did HSC at night school.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on July 23, 2022

at 2:07 pm

Interestingly, I didn’t have a great teacher that year but I had a good friend who loved literature too and we taught ourselves… though in retrospect that teacher was probably better than we thought at the time. She was a funny old sausage!

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on July 23, 2022

at 5:51 pm

I don’t remember any of my school peers being even remotely interested in reading.

But of course they may just have kept quiet about it, like I did.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on July 23, 2022

at 5:55 pm

I had a great group of academically-oriented friends, and this particular one who shared a love of reading. It was a state school too … but one of Sydney’s state girls’ schools.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: whisperinggums on July 23, 2022

at 5:58 pm

I adore Voss … it was the book that sold me on White when I was around 18 …. I have planned to read it with a friend who’s never read it. Maybe we could do it then but I shy from making commitments these days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: whisperinggums on July 23, 2022

at 5:21 pm

Alas, I think we’ve all learned the folly of that with Covid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on July 23, 2022

at 5:35 pm

I just love the way Patrick White writes. He is not the most eloquent of writers but he draws you in with his strikingly descriptive style.

LikeLike

By: australianonlinebookshop on June 9, 2009

at 11:55 am

Yes, I did get a bit carried away *chuckle*.

I loved it so much, and I wanted to make sense of my thoughts…

Lisa

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on June 9, 2009

at 2:57 pm

I’m so glad you liked it – it’s such a great book. I do hope my f2f group agrees. Some are being dragged kicking and screaming I think.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on June 9, 2009

at 4:18 pm

Terrific post Lisa.

I first read Voss as an 18 year old and loathed it beyond all loathing; read it at 45plus and loved it. In fact, I’ve enjoyed every Patrick White I’ve read now (although suffered through his play The Ham Funeral).

LikeLike

By: Janine on June 9, 2009

at 6:35 pm

I suspect that this happens a lot, Janine. Well-meaning teachers and university lecturers put it on the book list because they want students to get to know our only Nobel Prize winning author – but really, I think one needs to be an experienced reader to fully appreciate his mastery. As you can see from my post, there were plenty of bits of Voss that I found mystifying, and I’ve been reading modernist novels for years.

Now I have to decide which one to read next: The Twyborn Affair? Riders in the Chariot? The Eye of the Storm?

Or should I read the bio by Patrick Marr first? So much to choose from, and not enough time to read!

Lisa

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on June 9, 2009

at 7:56 pm

I read it for year 12 when I was 18 and adored it! But one of my f2f group friends was a bit horrified at my suggestion because she felt she’d done it to death then. I thought it was the perfect novel for adolescents – girls in particular – so romantic! My best friend at the time and I we got right into it. I have more Whites to read too and I’m not sure which next.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on June 9, 2009

at 9:40 pm

It could appeal to a feminist strand as well, Laura being so uppity for a lassie in those days LOL.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on June 9, 2009

at 10:00 pm

[…] other people. I’m not stuffy about style, form or period – since my adventures with Voss I’ve come to appreciate modernism as much as the 19th century novels I grew up […]

LikeLike

By: Opportunity, by Charlotte Grimshaw « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on August 2, 2009

at 10:07 am

Wow, Lisa. I don’t even know where to begin with a comment. I haven’t heard of Patrick White before (hands head in shame), but I love the passion that you exude in this review for his writing and the style. I’ve always been really interested in the Modernist movement and especially some of the themes you outline here–themes that immediately remind me of Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night. Have you read that one?

I’ll definitely be looking into this one.

LikeLike

By: Trish on August 10, 2009

at 11:30 am

Thanks, Trish for your kind comments, and also for the suggestion re Tender is the Night. I have read it, but a while ago – in what way are the themes similar? Obsessions?

TITN is a fine book and I very much like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s style. I read The Great Gatsby so long ago that I really should read it again… I read The Curious Tale of Benjamin Button when the film came out, and I have a lovely set of his short stories given to me by a friend to look forward to.

My next adventure is going to be with post modernism – about which I know nothing!

Lisa

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 10, 2009

at 1:47 pm

[…] pity that our only Nobel prize winning writer is neglected so shamefully. I’ve posted from my soap box about this before…. Possibly related posts: (automatically generated)My baby can […]

LikeLike

By: The Solid Mandala by Patrick White « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on August 15, 2009

at 9:01 am

Never mind White winning the Nobel prize, you should get it for this post! Excellent stuff. Makes me want to read this book more than ever now. When I do I will come back here, for reference, and to let you know what I thought.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: kimbofo on August 16, 2009

at 11:26 pm

Yes. I think I needed to read this prior to my journey. It may well have assisted.

LikeLike

By: fourtriplezed on October 15, 2017

at 9:46 am

[…] Riders in the Chariot won Patrick White his second Miles Franklin Award in 1961, five years after Voss took out the inaugural award in 1957. I haven’t read it yet: I want to read The Twyborn […]

LikeLike

By: Opening Lines: Riders in the Chariot « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on September 19, 2009

at 11:46 am

[…] whose Classics, Books for Life inspired my choice of this book for the challenge (she selects Voss for inclusion in Australian Classics) writes that The Twyborn Affair was a bestseller for […]

LikeLike

By: The Twyborn Affair, by Patrick White « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on September 26, 2009

at 3:41 pm

So well done, Lisa. I offer from memory some fervent comments.

One is almost sedated as we read, “…fluttered around him and settled on the grass, like a mob of cockatoos”, soon followed by ‘They went walking through the good grass…’ Aren’t the parallels poignant between Dugald and Jackie’s ultimate betrayal?

In view of the ending, how pregnant is this quote! ‘For PART OF ME has now gone into it. Do you know that a country does not develop through the prosperity of a few landowners and merchants, but out of THE SUFFERING OF THE HUMBLE?

Goat’s milk, appropriate for a poet with diarrhoea in the desert, seems to Voss too little too late. Increasingly desperate, he clutches at illicit poetry, which proves bizarre and incomprehensible mirroring perfectly the fateful expedition. That ‘Le Mesurier seems first to will himself to die’, shows that EVEN THE POET finally loses hope in the desert (rather than ‘to pre-empt them killing him’)! The words of his poem, ‘fevers turned him from Man into God’, have resonance in the ending when Judd suggests Voss had learned he was only a man. And the poet’s prayer ‘that his spirit will live on’ is answered in Laura, following Judd’s last testimony.

In imitation of Christ, Palfreyman ‘takes on the sins of the others’, which Judd tellingly misconstrues as Voss in his final testimony. Judd chose ‘to go on this expedition’ because, like Laura, he believes that ‘Man shall not live by bread alone’.

While Voss sneers that ’small minds quail before great enterprises’, only a poet with no future, a simpleton martyr and the local lad, Jackie, follow Voss to damnation. As the feverish Laura rides alongside the suffering Voss, we see both Voss’s delusions and Laura’s vicarious suffering. Does Laura offer up ‘Mercy (the child) as a sacrifice, so that Voss may survive’? No, Laura freely chooses to suffer in sympathy with Voss. Do ‘the three pears that go off’ symbolise the death of three ‘wise’ men from the east following a star? I wish I still had the novel!

At first, the aboriginals ALSO mistake Voss for God, in a latter-day epiphany! But as the comet fades, Jackie, like Judas, betrays his fallen God for a pittance dying in a ‘swamp’ of alienation.

Years later at Belle’s party, Laura is still in mourning and is terrified of hearing from Judd dreadful tidings of a proud and heartless visionary. To her utter relief, Judd relates Voss humbly ‘washing the sores of the others’. Brimming with messianic metaphor, a befuddled Judd says ‘he was there when Voss was speared’ (John 19:34__‘But one of the soldiers with a spear pierced his side’). Timid no longer, Laura’s repeated ‘I am content,’ to Colonel Hebden has the power of a Jove thunderbolt! And nothing in the novel is more ironic than Laura’s, ‘he struggled with that evil. AND FAILED.’ The triumphant and serene Laura deals effortlessly with the vexatious, drunken Englishman.

LikeLike

By: Gladys on September 28, 2009

at 10:15 pm

You know, Gladys, if anyone out there is studying Voss at school or uni, they are going to be rapt when they come across these interpretations – and all from your memory! I don’t know how you do it.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 28, 2009

at 10:41 pm

I find, Lisa, that some friends reading White are too quick to attribute figurative meaning while discarding the literal. Here are anomalies that helped me with the ending.

Why does a crestfallen Laura believe Judd’s last testimony despite Colonel Hebden’s justified scepticism? If ever there’s an unreliable witness, it’s Judd: an old ex convict, with no education, who lived in a shack in the bush, damaged by years in the desert with Aborigines, now without home or family and contradicting himself though dementia. Yet Laura weighs up the Colonel’s stainless objectivity alongside the passionate subjectivity of Judd, a practical and pragmatic man, who once purchased and housed a telescope to look up at the heavens and, later, joined an expedition with poet and pastor, lead by a visionary.

Judd reminds me of insightful Miss Shrimshaw in ‘A Fringe of Leaves’, of whom we read, ‘she was too engrossed, her onyx going click click, shooting down possible doubts; for however much crypto-eagles ASPIRE TO SOAR, AND DO IN FACT, through thoughtscape and dream, their human nature cannot but grasp at any circumstantial straw which may indicate an ordered universe.’

After Judd’s testimony, why does Colonel Hebden, a self-assured military man of impeccable objectivity, nervously avoid insignificant Laura? Why is Belle suddenly put out at the attention given to Laura at the party? And how has Laura, a reclusive spinster in mourning, silenced a bombastic and drunken English gentleman, defaming her late fiancé?

LikeLike

By: Gladys on September 29, 2009

at 3:13 pm

I’m a bit baffled by all this, Gladys. I thought it was a matter of Laura believing what she needed to believe, but I also think that White is playing around with ‘social occasions’ that mask truth (whatever that may be).

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 29, 2009

at 4:06 pm

Baffled, Lisa? Patrick White’s depiction of ‘social occasions’ – here and elsewhere – clearly highlights, rather than masks, the truth. I think ‘truth’ with strong existential overtones is the major theme in ‘Voss’. Patrick White’s ‘truth’ is lived out moment-to-moment, rather than selected facts believed.

Many – including Belle, Tom Radclyffe, Angus and Turner – are content with down-to-earth goals. Voss, Laura, Judd, Le Mesurier, Harry Robarts, Palfreyman and Jackie are seeking for truth of a more spiritual kind. They are unsatisfied with the sterile, objective truth that Colonel Hebden seems after. From an objective standpoint all seem to do poorly. But that’s only half the story: to quote Soren Kierkegaard, ‘Subjectivity is truth.’

Laura ultimately believes that Voss in the desert achieved humility, a goal she had set for him. In dire circumstances, he learns to conquer his pride and vanity. Far from ‘Laura believing what she needed to believe’, she and Voss bravely LIVE OUT something akin to truth, and Voss fails ONLY in the shallow sense that he and others die – ‘shallow’ in that death comes to all of us. This victory of the spirit, this lived out truth, is what bothers the intuitive colonel as he steers clear of the exultant Laura. Perhaps only the colonel and Jackie, like Judas before him, fail completely in the end.

Can you point to flaws in my reading of the text, Lisa?

LikeLike

By: Gladys on September 29, 2009

at 6:05 pm

Point to flaws in your reading? No, certainly not… I’m afraid I’m out of my depth here, Gladys… Lisa

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 29, 2009

at 6:13 pm

Your blogs, Lisa, are of such a high quality that I’m astonished you feel out of your depth. I’m sure you’ve read more widely because I started reading fiction five years ago and am a very slow reader. I have so much enjoyed our discussion of White’s novels, and any criticism of my readings adds to that enjoyment.

To question my interpretation, you would only need to propose a verbal exchange or an incident in the novel that seems at odds. Perhaps you overestimate the complexity of modernist novels. Admittedly my fair knowledge of Scripture, existential philosophy and scientific method are quite an advantage.

Am I unusual in playing rapid scenarios in my mind, hours, days and weeks after reading Patrick White, Ibsen, Dostoevsky, and others – often on waking from sleep?

LikeLike

By: Gladys on September 29, 2009

at 8:10 pm

[…] Lines: Voss (1957) Voss, by Patrick White won the inaugural Miles Franklin Award in 1957. These are the opening […]

LikeLike

By: Opening Lines: Voss (1957) « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on October 17, 2009

at 6:36 pm

Thanks for this post. i am currently studying Voss at uni and have struggled a little with this novel..

If you have any suggestions about the importance of chapter 13 and how it is important for the novel as a whole that would be handy! :D

but as i said thanks for this Lisa it has given me a lot more insight into the novel!

Christine

LikeLike

By: Christine on November 5, 2009

at 12:28 pm

Hello Christine, I’m glad you find my ramblings helpful:)

But as to chapter 13, Voss is nearly 50 books ago for me now, and so I’d have to go and dig out the book out to refresh my memory as to what it was all about…

And since I’m not the one doing the essay – I’m not going to do that! *grin*

Lisa

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 5, 2009

at 6:52 pm

As mine was a library copy, Christine, what happens in Chapter 13?

LikeLike

By: Gladys on November 5, 2009

at 7:52 pm

it is the chapter where Voss dies. its all good have already finished it! :D

LikeLike

By: Christine on November 6, 2009

at 1:07 pm

Voss, the fallen god, dies! As Laura jubilantly asserts: he learned humility in the wilderness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Gladys on November 6, 2009

at 1:29 pm

[…] Voss (1957) by Patrick White (Australia) […]

LikeLike

By: Top Tens 2009 « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 27, 2009

at 1:47 pm

Just finished Voss – the fourth White novel I’ve read.

Wow. It’s Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to the power of 10, with some Jane Austen thrown in. The work of a master craftsman and, dare I say it, genius.

LikeLike

By: Evan on February 12, 2014

at 12:41 pm

No arguments from me about that, Evan! Which other ones have you read?

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 12, 2014

at 8:55 pm

The Aunt’s Story, The Tree of Man and The Solid Mandala. Phenomenal novels, all three. Now Voss joins their company. Next up, Riders in the Chariot (but I’ll need to take a little break first -White does that to you…)

LikeLike

By: Evan on February 12, 2014

at 9:45 pm

Yes I agree, though my favourite is The Aunt’s Story. LOL I’ve been rationing myself to one-per-year to try and stretch them out, which is still, I know, because of course they all repay re-reading anyway. But I haven’t read Riders in the Chariot yet, I should read that one this year…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 13, 2014

at 6:07 pm

This post and the comments following win the internet, I say.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Joh on March 22, 2014

at 10:44 am

[…] post is going to be one of those ‘written-as-I-read-it’ ones (like Voss, Don Quixote and Tale of the Tub) because I want to record what I find interesting as I read it and […]

LikeLike

By: A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads, by Anthony Reid (and thank you to Kingston Library) | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 9, 2015

at 12:00 pm

As was written in the comments by Gladys. “knowledge of Scripture, existential philosophy and scientific method are quite an advantage. ” With that I feel out of my depth :-).

LikeLike

By: fourtriplezed on October 15, 2017

at 9:53 am

Well, yes, but as I said in my reply to you at Goodreads, reading some books is more like a research project. I never went to Sunday School so my knowledge of scripture is very scanty, I know nothing about existential philosophy and my knowledge of scientific method dates back to secondary school science. I was out of my depth too, so I looked things up when I needed to, and that made me enjoy the book more, partly because I understood the book better, and partly because I enjoyed learning new things through the research. An entirely different experience to reading a book that is less dense and challenging!

But – as will be obvious to anyone who knows this book really well – I didn’t always know when I didn’t know something. (unknown unknowns!) But, I wasn’t reading this book to pass a test or gain a PhD, I was reading it for fun, so I was free to tackle it any way I like and while I’m interested in hearing from others more expert than me, I’m immune to criticism about my reading of it.

One thing I will say: this post about Voss has been viewed over 10,000 times, my guess is that half of those are students ‘doing’ the book, and the other half are their teachers checking student assignments for plagiarism!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 15, 2017

at 10:36 am

[…] I reserve them for spectacular books like James Joyce’s Ulysses and Patrick White’s Voss so I didn’t rate anything with five stars last year even though I really, really liked many […]

LikeLike

By: Six Degrees of Separation, from Atonement, to … | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on August 4, 2018

at 10:58 pm

[…] title: Tasmanian Aborigines: A History since 1803, by Lyndall Ryan (15,406 views since 2012) and Voss, by Patrick White with 11,124 views since 2009. and the ANZLL Indigenous Literature Reading List with 8,504 views […]

LikeLike

By: 2020: ANZ LitLovers stats | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on January 4, 2021

at 9:51 pm

[…] to home Lisa @Anz LitLovers has blogged about her experience of reading Voss in 2009. She inspired me with these words, to […]

LikeLike

By: Voss Readalong – Getting Ready on October 30, 2022

at 7:43 am

Thank you for this detailed review. A few months ago, feeling I had a duty to read White, I bought a copy of “Voss” on impulse. I must confess I nearly stopped reading at the sentence on page 9: “The light was ironical in her silk dress.” Apart from my feeling that the word should be “ironic”, what does this sentence actually mean? However, I made it to the end, and even found parts of the novel impressive and moving, but I have to say that White’s style gets in the way rather than helps – for this ignorant British reader, at least.

LikeLike

By: bikerpaul68 on October 10, 2023

at 8:19 pm

Well, I’m glad to have helped a bit!

As I understand it ‘ironical’ has been displaced by ‘ironic’, it’s just modern usage compared to its usage more than half a century ago.

In the sentence you’ve given, I would suggest (without actually knowing the context) that since irony is a state of affairs is deliberately contrary to what’s expected, the light shining on her dress doesn’t give the impression she was aiming for. Maybe it shows her figure flaws. Maybe the colour doesn’t suit her skin colour. Maybe she meant to look elegant but she hasn’t dressed for the occasion, whatever it is.

And the point about using a deliberately awkward sentence like this is that it makes you focus on it. Nine times out of ten we read what a character is wearing and it makes no impression on us. We don’t care what the character is wearing and we don’t notice its effect. But this sentence of White’s makes us pay attention. The fact that she is wearing a silk dress is important in some way.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 10, 2023

at 9:16 pm