My generation grew up knowing the name of the artist Margaret Olley. As Bill Hansen and his photos are to Gen X and Y, we were familiar with William Dobell, Sidney Nolan and the rest of the Heide Circle, Donald Friend, Russell Drysdale and Olley. (Olley was, as Clive James puts it on his blog, ‘Women’s Weekly famous’. ) Without really knowing what Modernism was, and none of us able to afford to buy any of it, nevertheless we saw the work of Australia’s modernists in newspapers and magazines, around us in public spaces, and here in Melbourne at the NGV.

My generation grew up knowing the name of the artist Margaret Olley. As Bill Hansen and his photos are to Gen X and Y, we were familiar with William Dobell, Sidney Nolan and the rest of the Heide Circle, Donald Friend, Russell Drysdale and Olley. (Olley was, as Clive James puts it on his blog, ‘Women’s Weekly famous’. ) Without really knowing what Modernism was, and none of us able to afford to buy any of it, nevertheless we saw the work of Australia’s modernists in newspapers and magazines, around us in public spaces, and here in Melbourne at the NGV.

So I was looking forward to reading this biography of Margaret Olley. I enjoy reading books that enlighten me about how artists make art, my favourite of which is Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth. (I did not study art at school or university and my understanding of it is entirely self-taught. I saw The Shock of the New, and bought the book, but it was Carey’s modernist novel which taught me to look at modern art in an entirely different way.)

There are lots of things to enjoy in this book. Gossip about notables in the art world is entertaining, and I enjoyed Olley’s journey from childhood to old age. I was fascinated by what she did, and bemused by the way important world events such as World War 2, the birth of nuclear warfare and all the -isms which influenced her compatriots seem to have passed her by. I was amused by her philosophy on domestic ensnarement: I used to observe how people became like each other and like their animals as they got older; not only did they look the same, they hardly spoke to each other because they had nothing to say.’ (p373). I was astonished by her assessment of Newcastle as a painterly city, and have resolved to look at it with different eyes next time I’m in the Hunter Valley. I liked reading about how and when she made her paintings, the reviews of her work and her friendships with other artists. It was interesting to discover some that I didn’t know too.

But perhaps it is because Stewart is from the Sydney art world herself that she has made certain assumptions in this book, for despite its length, (506 pages, not counting the references and notes) I found myself having to look things up online and in books. Sometimes, allusions are frustrating for the general reader, at other times stories are only half told. The controversy over Dobell’s portrait of Joshua Smith winning the Archibald Prize is not explained with sufficient clarity for generations not yet born to witness it, and there is coyness about Donald Friend’s pagan pederasty, quoting the man’s reference to ‘his own peculiarities‘ (p308) without any explanation. Did Olley know or care about these peculiarities when she proposed to Friend, or later?

I also wanted to know more about Olley’s style, and there are references to it throughout the book (especially towards the end) but it was online at the Australian Government’s Culture Portal that I found a succinct explanation and a summary of her oeuvre that made sense to me.

Not easily swayed by changing fashions and movements of the art world, Olley chose to paint her immediate world, immersing herself in everyday subjects that reflected her interest in the personal and the intimate:

The art of Margaret Olley is the art of deliberate choices. The same could be said of Olley herself, who dispels all theories of Australia’s isolation, repression of women and fashion following. (…) she persists in painting that which is around her; one reason for this is loathing of pretence, of adopting ways of thinking that are not true to the reality of self.

France, C 2002, Margaret Olley, Craftsman House, Sydney, p.13

I don’t doubt her talent – I can see it for myself – and I can also see how commercially successful her style would be. Her paintings would grace most sitting-rooms in a way that the darker themes of her male compatriots might not; they’re not confronting at all, either in style or subject matter. This tempts me to wonder why Stewart did not explore in more detail why Olley did not engage with contemporary issues in her art work…

Brenda Niall (‘Tyranny of the Tape Recorder’) in her review of this biography for the ABR, wrote that Stewart had overdone the quotations from Olley herself, and it does seem as if she has succumbed to the voice of her subject in many places. Curiously, however, this ubiquitous voice seems to mask the real Olley. Despite the author’s obvious affection for her subject, there are hints of occasional frustration or irritation when Olley ‘won’t tell’; on the other hand, Stewart seems reluctant to reveal her own thoughts about Olley or to tackle anything ‘difficult’.

I wanted to know more about how Olley because wealthy enough to become a significant donor of art to the NSW Art Gallery. She was obviously canny with real estate, but was it immediate success with selling paintings back in 1962 that enabled her to make that first foray into home ownership? Now in her old age she flits about the world with astonishing agility for someone of her age, but I bet it’s in first class on the long haul trips. Did Stewart think it was vulgar to find about this matter of interest, in a country where it is rare for any artist to be able to make a living in Australia? I know that Olley’s paintings sell today for tens of thousands of dollars, but when they change hands now, it’s not Olley who receives the money, it’s the investor. At what stage in her career did she become so ‘bankable’ ? Has her commercial success limited her development as a painter?

Stewart also has occasional annoying lapses into referring to her own bits of trivia. On p368 there is a reference to dancing and quaffing wine from a penis-like serpent’s head. I coudl not make sense of this until I remembered that it referred to a night of high jinks with her friends. Hardly worth reminding us of this, I thought, nor did we really need to know that she cut her leg in 1966 (p384). (Who was it who said that the secret of being a bore is to tell everything?)

I felt that Stewart idealised Olley’s childhood a bit, probably because Olley did. She and her siblings never fought, and were always sensible? Really?? (pp36-7) And then the commentary on the Depression: it seemed to me that the reason it barely touched their lives was because the family were landholders and could be self-sufficient on their farm. It could be that Olley has led a somewhat sheltered life, and that is why she paints domestic interiors and still lifes over and over again. That’s not an idea tackled in this biography.

I was annoyed when paintings were described but not named so I couldn’t identify them. Apparently there’s a ‘haunting work’ of a model ‘lost in thought beside a pale bunch of Eucharist lilies’? (p351) Great. What’s it called? There’s also a bunch of nudes of interest too, ‘women langorously resting from tropical heat and the outside world in a coolly luscious retreat’ – but they’re not named either. What is the point of telling us that Gertrude Langer complained that they had ‘no social comment or context’ when we can’t decide for ourselves because we don’t know what they are?

On page 355 Stewart tells us about the disaster that befell Ian Fairweather’s paintings, tells us that Fairweather was suspicious about foul play to the point of paranoia – but not about what really had happened to the pictures – and although she comes back to it 50 odd pages later she doesn’t explain who did it or why. On page 360 she talks about the portrait of Bell that no longer exists, but doesn’t tell what happened to it.

Please see my **Update below before reading on. What surprised me is an error on p472. Referring in considerable detail to Olley’s painting Homage to Manet

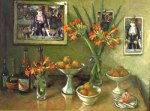

Please see my **Update below before reading on. What surprised me is an error on p472. Referring in considerable detail to Olley’s painting Homage to Manet , Stewart explains that the painting reproduces the whole of Manet’s famous work The Balcony (see at upper right). As with many other paintings referred to in this biography, I looked for it online, interested to see how it was done. (There are some full colour photos of Olley’s paintings in the book, but not this one). As you can see, Olley’s picture on the left references a very famous painting, but The Balcony it’s not. It’s a reference to Manet’s The Bar at the Folies-Bergere (see at lower right).

, Stewart explains that the painting reproduces the whole of Manet’s famous work The Balcony (see at upper right). As with many other paintings referred to in this biography, I looked for it online, interested to see how it was done. (There are some full colour photos of Olley’s paintings in the book, but not this one). As you can see, Olley’s picture on the left references a very famous painting, but The Balcony it’s not. It’s a reference to Manet’s The Bar at the Folies-Bergere (see at lower right).  (Olley has also done this with paintings by Renoir and Rembrandt, which you can see on the Phillip Bacon Gallery site). I am amazed that Stewart – with her background in the arts – made this mistake, and even more amazed that her editor didn’t pick it up. Maybe Random House don’t have a specialist arts editor any more, and think that managerialism works in the editing business as well? Who knows? Whatever the case, it’s made me doubt the credibility of Stewart’s commentary about Olley’s paintings. I think that an artist of Olley’s stature deserves better than this…

(Olley has also done this with paintings by Renoir and Rembrandt, which you can see on the Phillip Bacon Gallery site). I am amazed that Stewart – with her background in the arts – made this mistake, and even more amazed that her editor didn’t pick it up. Maybe Random House don’t have a specialist arts editor any more, and think that managerialism works in the editing business as well? Who knows? Whatever the case, it’s made me doubt the credibility of Stewart’s commentary about Olley’s paintings. I think that an artist of Olley’s stature deserves better than this…

There is an excellent timeline of Olley’s life at Philip Bacon’s site, and you really should have a look at this brilliant photo by R. Ian Lloyd of Olley at work in her studio.

I think my favourite quotation from Margaret Olley was the one about housework;

I’ve never liked housework. I get by doing little chores when I feel like them, in between paintings. Who wants to chase dust all their life? You can spend your whole lifetime cleaning the house. I like watching the patina grow. If the house looks dirty, buy another bunch of flowers, is my advice. (p438)

Olley’s painting in this post was sourced from the Phillip Bacon Galleries, where you can also see many others.

Update: July 27th 2011

Margaret Olley died yesterday, aged 88. For a short time you can see some of her work, and portraits painted with her as the subject at this link on the ABC website.

**Update August 16th 2011

As you can see in comments below, I owe Meg Stewart and her editors an apology for this interpretation. As with many other paintings that Stewart had referred to, I was interested to see what Homage to Manet looked like. In the book there was no illustration of the painting and no reference to which gallery it was held in. I looked through all the Australian art books we have and then went hunting online for it. The one at the Art Gallery of NSW which references The Balcony didn’t appear in my 2009 searches at all. If it had, I would of course have recognised it as the one that Stewart refers to. (Please click the link to see the painting, I can’t show it here for copyright reasons). What I found instead after extensive searching (on June 13 2009), was the one referencing The Bar at the Folies-Bergere attributed to Margaret Olley. It was named as Homage to Manet.

Although that’s not where I found it back in 2009, as of today, at metagini.com this same image is also labelled as ‘detail from Homage to Manet’. If that’s not its name, I haven’t been able to find out what it’s called instead and would be very pleased if someone could tell me what it is. (Clearly it is a homage to Manet if not the Homage to Manet). This painting is also on the front cover of Margaret Olley, Edouard Vuillard: Still Lifes and Interiors by Barry Pearce, Philip Bacon Galleries, which appears to be a catalogue of paintings exhibited at the Lismore Regional Gallery in June 2006. I have contacted the NSW Library to find out if the name of the painting can be ascertained from the book.

However whatever it’s called, it is quite clear now that I’ve re-read page 472, that the painting which Meg Stewart described is the Homage to Manet at the the Art Gallery of NSW. It was an honest mistake but I apologise unreservedly to Meg Stewart for my comments.

Further update August 25th 2011

It seems that there are indeed two paintings by Margaret Olley called Homage to Manet’, the one at the Art Gallery of NSW painted in 1997, and another one done in 2005.

It seems that there are indeed two paintings by Margaret Olley called Homage to Manet’, the one at the Art Gallery of NSW painted in 1997, and another one done in 2005.

The State Library of Victoria has two copies of the catalogue ‘Margaret Olley, Edouard Vuillard: Still Lifes and Interiors’, one of which features a cover with a detail of Homage to Manet (2005). The detail comes from the painting shown on the LHS above and it references Manet’s The Bar at the Folies-Bergere. I owe thanks to Katie Flack, the Collections Coordinator in the Australian History & Literature Team, who checked both versions of the catalogue for me and provided the following information:

The catalogue produced for the Sydney showing of the exhibition (Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, exhibiting at Sotheby’s Gallery Sydney, 28 Sep to 15 Oct 2005) shows a detail of Homage to Manet (2005) on the front cover, and Self portrait III (2005) on the inside front cover.

The catalogue produced for the London showing of the exhibition (3 to 18 Mar 2005, Nevill Keating Tollemache) has a different cover, showing Gloriosa lilies and apples (2004).

So the painting which I originally found online, which references Manet’s The Bar at the Folies-Bergere and which I used as the basis for my criticism above is actually called Homage to Manet as well. The mystery is solved…

Its great to be reminded of the cultural history of Australia – a topic we don’t hear too much about over here in the UK.

A very interesting and informative post!

LikeLike

By: Tom C on June 14, 2009

at 6:29 pm

When I saw you were reading this I thought that it was a book I’d like to read, but now I’m not sure. I read, many years ago now, Meg Stewart’s Autobiography of my mother and really enjoyed it. But that was an intriguing book and far more personal so perhaps she did it better. And it was about Sydney and the arts/literary scene that, having lived in Sydney for a while, I found fascinating.

I do however love the housework quote. I have a lot of dust patina in my house. I reckon it’s better to let it lie than disturb it!

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on June 14, 2009

at 6:51 pm

I must admit I would like to see the previous bio by Christine France. It was only published in 2002, so I suspect that the publishers were cashing in on the public enthusiasm for biography with Stewart’s one. Lisa

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on June 14, 2009

at 7:20 pm

[…] am intrigued by Ian Fairweather because of references to him in Margaret Olley, Far from a Still Life. He was a recluse, and I confess I had never heard of him until I read the rather bizarre […]

LikeLike

By: Fairweather by Murray Bail, and Fred Williams by Patrick McCaughey « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on August 2, 2009

at 12:27 pm

I am fascinated by the number of hits this post has had (514 to the end of October, since June, and my 3rd most popular post). I wish someone who drops by would tell me why it’s so popular! Please, leave a comment if you have a particular reason for visiting, thanks:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 26, 2009

at 8:02 pm

[…] book illuminates for me the process of painting a still life. I wish I had known, when I read Meg Stewart’s biography of Margaret Olley, just how tricky it can be to make the flowers […]

LikeLike

By: Time Without Clocks, by Joan Lindsay « ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 15, 2009

at 7:51 am

I think you need to look at ‘Homage to manet’ painted by Margaret Olley in

1997. Its location is at the National Gallery Of NSW. You have not put me off this book in fact I may go out and buy it now! Get your facts right next time!!

LikeLike

By: Leanne on August 16, 2011

at 1:30 pm

Hello Leane, and thank you for setting me straight. Here indeed is Olley’s Homage to Manet at the art gallery (1990) http://tinyurl.com/3px7kou but where is the one that I found, and what is it called? (This is where I found it, http://tinyurl.com/3h3azga where (scrolldown) it’s labelled as the detail from Olley’s painting. And here it is again, on the cover of a book by Edouard Vuillard http://tinyurl.com/3oxrb48

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 16, 2011

at 2:07 pm

Hi Lisa

That’s ok, maybe I was a bit abrupt, but it is annoying when people get things wrong, especially about art. It happens all the time. I know margaret Olley painted a few of manet’s paintings so there are probably more you don’t know about. Its nice to know you are on the ball. Cheers Leanne

LikeLike

By: Leanne on August 18, 2011

at 12:19 pm

Thanks, Leanne, I’ll do a further update when the State Library gets back to me with the name of the mystery painting. They’re renovating at the moment so there will be a delay, I think.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 18, 2011

at 12:44 pm

[…] learned about the slow reading movement on a site that discussed Margaret Olley, the painter whose work I viewed during a recent sojourn in […]

LikeLike

By: Slow Reading Movement « WorldReader on March 28, 2012

at 6:28 am

[…] own analysis of events. It is this perceptive analysis which sets this biography apart from the Margaret Olley biography which relies too much on commentary […]

LikeLike

By: Stella Miles Franklin, A Biography by Jill Roe | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on March 11, 2016

at 12:06 pm