My introduction to Eleanor Dark (1901-1985) came at school in 1967 when I was given No Barrier as a prize. Published in 1953 it was the last one of a trilogy of historical novels comprising also The Timeless Land (1941), and Storm of Time (1948) but although I loved No Barrier, it was a long time before I stumbled across the other two titles in OpShops. Her oeuvre was, I thought, long out-of-print, but a lucky find at the library led me to a title I hadn’t read, Lantana Lane, reissued in 2012 by Allen and Unwin as one of their House of Books collection.

My introduction to Eleanor Dark (1901-1985) came at school in 1967 when I was given No Barrier as a prize. Published in 1953 it was the last one of a trilogy of historical novels comprising also The Timeless Land (1941), and Storm of Time (1948) but although I loved No Barrier, it was a long time before I stumbled across the other two titles in OpShops. Her oeuvre was, I thought, long out-of-print, but a lucky find at the library led me to a title I hadn’t read, Lantana Lane, reissued in 2012 by Allen and Unwin as one of their House of Books collection.

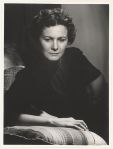

Eleanor Dark is well-known to authors in Australia because through the generosity of her son Michael her home in the Blue Mountains at Katoomba is Australia’s only national residential writers’ house for writers. It’s called Varuna – The Writers’ House and it offers a variety of support programs for the Australian writing community. Its alumni includes many authors whose works you will find reviewed on this blog: Glenda Guest, Toni Jordan, Deb Kandelaars, Paddy O’Reilly, Kristina Olsson, Favel Parrett, Jane Sullivan, Charlotte Wood and Fiona Wood. If you love Australian writing and feel minded to support it, a donation to Varuna is a way to help provide writers with time and peace to write.

Lantana Lane is Eleanor Dark’s last novel, first published in 1959. It’s a deceptively simple collection of comic vignettes about eccentric rural Australians that collectively form a picture of Aussie battlers living in the back-blocks of Queensland. They are hobby farmers, mostly retirees or people escaping the rat-race. Gentle allusions here and there point to Dark’s left-leaning political concerns: the very real threat of nuclear warfare in the 1950s penetrates even to the Sunshine Coast hinterland where the author based her story, and the narrator makes dire predictions about the environmental consequences of uncontrolled spraying with newly invented agricultural pesticides. Her characters are simple people, but not fools …

Their collective characterisation is perhaps idealised: as a group they are staunchly parochial about the vagaries of their weather, philosophical about fire and flood in ‘abnormal’ years, resilient in the face of disasters, tolerant of each other and generous with time and money well beyond their means. But individually, they are a weird and wonderful lot:

There is pretentious Mrs Herbie Bassett who (as seen in my recent Sensational Snippet) bullies her husband over the tenets of Gracious Living, and there is cantankerous Uncle Cuth whose aversion to soap-and-water and any kind of work causes grave difficulty when his current host, Joe Hardy, a ‘gangling, taciturn, middle-aged bachelor’ is badly injured by a flying sheet of corrugated iron during a cyclone. Gwinny Bell – likened to Brunhilde of Asgard – is the Lane’s indefatigable organiser in a community where almost everyone belongs to the town’s ‘imposing number of social, sporting and cultural bodies‘. The narrator wryly notes that her talents are wasted in the Lane and that considering the ‘muckle’ that the rest of the world is in, they could use her skills to help sort it out.

But all the women work hard. They have to:

We are not affluent people in the Lane. As primary producers we are, of course, frequently described by our legislators as The Backbone of The Nation, but we do not feel that this title, honourable as it is, really helps us much. We get by, but with nothing to spare – and we never know from one week to the next what is going to happen to the Market.

So when a fund is needed to help Joe Hardy get by,

… handing over a contribution to the house-to-house collection would by no means be the end of any family’s duty in the matter; indeed so far as the ladies were concerned, it would be but a bagatelle. They, as members of the Tennis Club, would make cakes for a Social, and then, as members of the C.W.A., make more for a Euchre Party, and again, as members of the Ladies’ Aid, still more for a Concert; next, as mother of Junior Farmers, they would provide supper for a dance, and as wives of Rotarians do the catering for a Monster Fair on the sports ground; after this they would apply themselves to the making of jam, tea-coseys, aprons, coconut-ice, felt rabbits and other useful articles to furnish stalls at fêtes under the auspices of the various Churches. Finally they would attend all these functions, surrender an entrance fee at the door, take tickets in a number of raffles, pay sixpence to guess how many beans there were in a bottle, and as the proceedings drew to a close, buy up as much flotsam and jetsam as might still remain on the tables, including, very probably, a coat hanger they had spent last evening covering, or half a chocolate cake baked that very morning in their own kitchen. (p. 49-50)

These affectionate portraits in this homage to rural living do not disguise Eleanor Dark’s awareness that this is a way of life under threat. The idiosyncratic marking of property boundaries in the Lane will only ward off the surveyors for a while; the road deviation is inevitable and it will destroy the comradeship of the Lane. Not only that, the spirit of community that sustains them in the wake of Cyclone Celestine won’t survive the inevitable consolidation of hobby farms into larger ones that are economically viable. The quaint insouciance about making so little money that they don’t have to pay tax doesn’t obscure the truth implicit in Lantana Lane: despite the optimistic tone, the fondness of the satire and the author wryly ‘cocking a snoot’ at the doomsayers beyond the lantana, there is no real future for these people and their anachronistic way of life.

And when you read the chapter about Biddy and Tim Acheson the former banker, and the hardships and debt they face, to me, it doesn’t seem like a lifestyle much worth preserving. Because as people prove in towns and cities as well as in small rural communities, community can form anywhere and everywhere that there are people of tolerance and goodwill.

Apart from one chapter (The Dog of My Aunt) which in my opinion verges on slapstick in its portrayal of the ‘new Australian’ Aunt Isabella, Lantana Lane is a flawless example of an author using her intimate knowledge of people to great effect. It’s a book of greater merit than its nostalgia value might otherwise suggest.

Author: Eleanor Dark

Title: Lantana Lane

Publisher: Allen & Unwin House of Books, 2012, first published 1959

ISBN: 9781743313367

Source: Kingston Library

Availability:

Direct from Allen & Unwin, and (I hope) discerning indie bookshops.

I’ve just finished it and I totally agree with your review, except that I enjoyed the slapstick more than you did.

I’m grateful for ebooks. Without them, I’d never be able to read books like this.

LikeLike

By: Emma on January 18, 2021

at 7:36 am

Well, you might be pleased to know that I have decided to host an Eleanor Dark Week in August to coincide with her birthday — and I’m pretty sure there are some more eBooks to be had at A&U’s House of Books…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on January 18, 2021

at 1:14 pm

I’m not sure I’ll make it, I’m usually on holiday in August. But who knows what’s ahead of us this year, right?

LikeLike

By: Emma on January 19, 2021

at 6:03 am

Indeed…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on January 19, 2021

at 11:18 am

[…] Visiting Lantana Lane was a great trip to Queensland, a journey I highly recommend for Dark’s succulent prose. For another take at Lantana Lane, read Lisa’s review here. […]

LikeLike

By: Lantana Lane by Eleanor Dark – an intelligent comedy about a community doomed to disappear. | Book Around the Corner on January 20, 2021

at 7:00 pm

Curiously, just a few kilometres north of Eleanor Dark’s Montville farm (where this was written) is a dead-end laneways called…Lantana Lane.

https://tinyurl.com/3xn74fyr

LikeLike

By: Marko on June 13, 2021

at 11:52 pm

Hi Marko, thanks for sharing this. ‘Lantana’ is a wonderful metaphor for tangled things that are out of control!

PS I’ve shortened your link using TinyURL.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on June 14, 2021

at 9:19 am

My mother’s family were farmers at Montville. If I posted a photo of my uncle Tom you would swear it was Joe Hardy. Uncle Tom always parked his green ute up by the roadside.

LikeLike

By: Helen Mackee on July 3, 2021

at 10:28 pm