The Intervention, an Anthology is an important book, so I would have liked its introduction to be better than it is. While it provides a vivid picture of how The Intervention has hurt Aborigines living in Northern Territory communities, it assumes from the outset that the reader already knows about what this Intervention entails, which made me wonder who the intended audience is supposed to be. If it’s supposed to be a call to middle Australians of good heart for their support, it gets off to a clunky start.

While Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory have been living with the Intervention ever since it was rolled out by John Howard’s government in 2007, it has faded from mainstream public consciousness elsewhere. That is obviously not as it should be, but (perhaps as a consequence of bipartisan political support) the mainstream media has moved on to other issues.

So for someone like me who has had no source other than the mainstream media to explain what the Intervention involved, it would have been helpful if the book began by explaining what this program actually meant in practice, i.e. in terms of government actions and of limitations on indigenous behaviour. But that’s not how the book begins. Instead there is an introduction by Rosie Scott which deplores ‘a number of drastic actions’ without saying exactly what they were; and then there’s another introduction by Anita Heiss about the need to pay homage to the heroes of the land rights movement and to galvanise action to have human rights reinstated, without saying clearly what rights had been taken away. Heiss directly addresses the claim ‘not to know’ and repudiates it:

Many older Australians who read my novel on the Stolen Generation will tell me ‘they didn’t know’. No Australian today can claim ‘not to know’ what is happening in the Northern Territory. (p. 13)

Well, all I can say to that is that I do my best to keep up with current affairs but I have failed this expectation. I remember some of the more contentious elements of The Intervention under Howard, and I was expecting the Rudd government to rescind it, so I was surprised when Minister Jenny Macklin approved its extension and there were high profile Aboriginal voices in support of that. It seemed a strange policy for a political party that had led the way in indigenous issues – from Gough Whitlam’s land rights reforms to Keating’s Redfern speech to Rudd’s Apology to the Stolen Generations – but I had faith in their good will.

I should add that I have always objected to the Intervention as a matter of principle on the grounds that it targeted a racial group not individual behaviour. It remains my belief that if any child, regardless of race or ethnicity, is subjected to neglect or abuse, then the state should intervene to protect that particular child. Any perpetrator, regardless of race or ethnicity, should – while having regard to his or her legal and human rights – be subject to the full force of the law. But to impose blanket provisions on any group of people based on the idea that they as a group are believed to behave in a particular way, seems to me to be morally wrong. But I must also acknowledge that contradictory positions held by eminent Aboriginal spokesmen and women on this issue led me to believe that it was a matter best dealt with by indigenous people themselves.

***

Anyway…

I consulted Wikipedia to find out exactly what the provisions of The Intervention were and how they differed from the Stronger Futures program (Wikipedia as viewed 13/9/15):

The Northern Territory National Emergency Response (also referred to as “the intervention“) was a package of changes to welfare provision, law enforcement, land tenure and other measures, introduced by the Australian federal government under John Howard in 2007 to address allegations of rampant child sexual abuse and neglect in Northern Territory Aboriginal communities. Operation Outreach, the intervention’s main logistical operation conducted by a force of 600 soldiers and detachments from the ADF (including NORFORCE) concluded on 21 October 2008. In the seven years since the initiation of the Emergency Response there has not been one prosecution for child abuse come from the exercise.

The measures taken via the $587 million package were

- Deployment of additional police to affected communities.

- New restrictions on alcohol and kava

- Pornography filters on publicly funded computers

- Compulsory acquisition of townships currently held under the title provisions of the Native Title Act 1993 through five year leases with compensation on a basis other than just terms. (The number of settlements involved remains unclear.)

- Commonwealth funding for provision of community services

- Removal of customary law and cultural practice considerations from bail applications and sentencing within criminal proceedings

- Suspension of the permit system controlling access to aboriginal communities

- Quarantining of a proportion of welfare benefits to all recipients in the designated communities and of all benefits of those who are judged to have neglected their children

- The abolition of the Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP).

With a change of government and a review, the Intervention became the Stronger Futures Program but is still subject to criticism because

- It excludes Aboriginal customary law and traditional cultural practices from criminal sentencing decisions

- It bans all alcohol on large swathes of Aboriginal land, and continues to suspend the permit system in Aboriginal townships, even though these measures have been opposed by the Northern Territory’s Aboriginal Peak Organisations.

- It provides excessively increased penalties for alcohol possession, “including 6 months potential jail time for a single can of beer and 18 months for more than 1.35L of alcohol.”

- It provides the Australian Crime Commission with “‘Star Chamber’ powers” when it investigates Aboriginal communities, overriding the right to remain silent.

- It provides police the right to “enter houses and vehicles in Aboriginal communities without a warrant” if they suspect alcohol possession.

- Makes laws “allowing for information to be transferred about an individual, to any Federal, State or Territory government department or agency, without an individual’s knowledge or consent.”

- It bans all “sexually explicit or very violent material” on Aboriginal Land.

- It gives the Commonwealth control over “local regulations in Community Living Areas and town camps.”

- It expands the School Enrolment and Attendance Measure (SEAM). Under the measure, parents of truant students (who are absent more than once a week) will receive smaller welfare payments. This action ignores “rising concerns among Aboriginal families regarding inappropriate education”

- The two thousand remaining paid Community Development Employment Program positions will be cut by April 2012. This is, in Stand for Freedom’s view, “the final attack on a vibrant program which was the lifeblood of many communities, employing upwards of 7500 people before the Northern Territory Intervention.”

- Changes proposed to the Social Security Act would constitute “further attacks on the rights of welfare recipients.”

Armed with this information that could usefully have been provided at the beginning of the book, I read on…

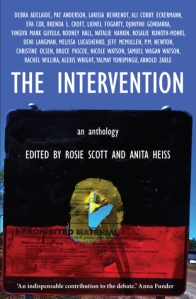

Excerpts in the anthology convey with great power the trauma that the Intervention has caused to people for whom self-determination was so hard won. There is poetry by Natalie Harkin, Lionel Fogarty, and Ali Cobby Eckermann, and there is fiction by Alexis Wright. Rodney Hall, Eva Cox and Arnold Zable lend a non-indigenous point-of-view to explain the constitutional connection; the relationship between bad policy and bad politics; and the potential for a meeting place between the Aboriginal and the Jewish search for lost ancestors. Strong Aboriginal voices in the form of memoir, press releases, political speech-making and deputations to our political leaders clarify the fundamental wrongness of the intervention: that it is a breach of human rights; that it failed from the outset to include community consultation so it was doomed to fail; that it marginalises and humiliates the people it is supposed to be helping, and that far from achieving its intended outcomes, it has actually made things worse on many key indicators. These Aboriginal voices include both the well-known and the less famous, but who mostly seem to be tertiary educated and media-savvy. These voices include amongst others Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, Pat Anderson, Larissa Behrendt, Melissa Lucashenko, Bruce Pascoe and Yalmay Yunupingu.

There are also compelling accusations that there was a hidden agenda behind the Intervention – that the urgent, militarised mission to rescue children from widespread child abuse – was a mask to enable the federal government to resume control of the valuable mining land. Equally compelling are the simple words of women and children recalling their fear when uniformed soldiers suddenly entered their communities with sweeping powers – because these communities have painful memories of having their children stolen away by men in uniform. In remote Australia with no access to TV, radio, telephone or the internet, many of these people had no forewarning and were terrified that a new form of missionary control was back, paternalistically interfering in their lives.

Amongst the many contributions which made me think again about The Intervention, was Rodney Hall’s discussion of constitutional issues. As a long-time supporter of an Australian Republic, I admit to feeling an intemperate desire to jettison the monarchy before Charles has any chance to become an embarrassing king. This desire for haste makes me tend towards any model that accomplishes this change quickly, but Hall has made me reconsider. He says, and I agree that it’s something we should have a national conversation about, that we should consider rewriting our horse-and-buggy constitution in its entirety. There is no particular reason why the modern nation of Australia could not exercise the same right to frame the nation as did the so-called founding fathers and update the Constitution so that it reflects who we are and how we run the country. This would enable us to include Aboriginal people and the environment to address the needs of a modern state (p. 185).

(Hall also points out that just how patronising [the Intervention] was can be measured by imagining what an outcry there would be if the government sent the same army personnel to intervene after accusations against the Roman Catholic Church. (p287) To which he might now add allegations of sexual abuse in institutions run by the Salvation Army, Geelong Grammar and a number of high profile Jewish schools).

In the blurb on the front cover, Australia’s President of the Human Rights Commission Gillian Triggs says that

This important collection … should be on school and university lists and pored over by book club members.

I think she’s right about that, with the caveat that you need to read the entire collection to get a real sense of what the problem is and why indigenous people in the Northern Territory deserve mainstream support to have their human rights restored.

Check out this review at Sharing Culture, from where you can find links to other reviews as well.

Editors: Rosie Scott and Anita Heiss

Title: The Intervention, an Anthology

Publication crowd-funded by ‘Concerned Australians’ 2015

ISBN: 9780646937090

Source: personal library, purchased by special order from Readings who now have copies in stock

Thanks for a helpful review Lisa, this book is on my to be read list & it’s good to have a picture of what’s in it. Seems strange they didn’t include an overview of the policies and actions though – I’m sure many Australians were not fully aware of the scope of the intervention and including the info would also make it more useful to international readers.

LikeLike

By: maamej on September 19, 2015

at 7:30 am

Good point, yes, because they have taken their case to the United Nations so that info would be useful for an international audience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on September 19, 2015

at 7:57 am

Sounds like a really interesting anthology. Your last paragraph of your intro describes just how I feel. Fundamentally there should not be such a program targeted indiscriminately to a group, but the different indigenous response was interesting. It was probably based on values: a philosophical one re self-determination and discrimination, and a pragmatic one of wanting to solve an immediate problem. I haven’t analysed it but I wonder if there was a level of gender divide in the response?

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on September 19, 2015

at 12:58 pm

I think that most of the people I saw on TV who were in favour of it were women, with Noel Pearson a notable exception.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 19, 2015

at 2:08 pm

Yes, that was my impression too. Without generalising too much – except I am I suppose – it can be the women who are practical. And I guess they are often the ones who suffer most too, either directly or picking up the pieces. So complex because it’s not only indigenous communities that have this issue!

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on September 19, 2015

at 4:18 pm

Indeed no. My mother used to say that during a war when everything is chaos, sometimes it seems not to matter who wins, you just want it to stop. But the big picture means that it does matter if the victor turns out to be like the Nazis.

But I still think that alarm bells should have rung all over Australia when the Racial Discrimination Act was suspended.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on September 20, 2015

at 8:13 am

Thankyou for this review Lisa and for stating your own convictions so forthrightly, I agree entirely. The Establishment hates land rights and winds them back at every opportunity. And the Labor Party does and says too little.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on September 20, 2015

at 9:20 am

I think it’s the bipartisan support that’s done the damage. Anyone who objects now is labelled ‘loony left’, in the same way that people who object to our asylum seeker policy are marginalised.

But the case for abandoning this intervention seems to be compelling on economic grounds, if no other. If it’s not achieving improved outcomes, any economic rationalist (of which there are plenty in the current government) would dump it. The fact that they haven’t done so suggests some other agenda, not just the land rights issue but also a sentimental attachment to a program identified so closely with John Howard, who is of course a Liberal hero…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 20, 2015

at 9:34 am

[…] been short-changed in the NT over decades and who’ve had to suffer the indignity of The Intervention because of the indifference of their governments. No wonder Territorians voted against statehood. […]

LikeLike

By: Crocs in the Cabinet, by Ben Smee and Christopher A. Walsh | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on February 11, 2017

at 11:08 am

[…] and with Anita Heiss in 2015 she co-edited The Intervention Anthology (see my review). […]

LikeLike

By: Vale Rosie Scott (1948 -2017) | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on May 10, 2017

at 9:44 pm

[…] my review) and with the late Rosie Scott also co-edited The Intervention, an Anthology (2015) (see my review). I have also read and reviewed her splendid Am I Black Enough for You (2012). But I have […]

LikeLike

By: Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms, by Anita Heiss | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on September 12, 2017

at 7:46 pm

[…] See my ANZ LitLovers review […]

LikeLike

By: 2018 Indigenous Literature Week – a Reading List of Indigenous Women Writers | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on June 5, 2019

at 11:31 am

[…] See my ANZ LitLovers review […]

LikeLike

By: Indigenous Literature Week – a Reading List of Indigenous Women Writers | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on June 5, 2019

at 11:35 am