I’m always surprised when a book is given a title that’s deliberately uninformative. Titles like John Berger’s G (see my review), John A Scott’s N (see my review), and Thomas Pynchon’s V (on my TBR). These titles tell you nothing at all about the book except that you’re meant to be intrigued. Obviously by intention, they eschew the usual idea of enticing a reader with a hint about the book’s content, character or theme, so there’s puzzlement even before the reader starts reading. Sometimes the book-cover is deliberately evasive too.

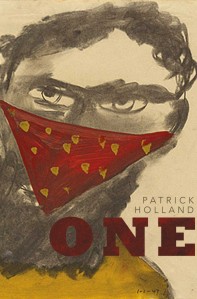

However, in the case of Patrick Holland’s latest novel One, cover art by the talented Peter Lo gives more than a clue. Nevertheless the significance of the enigmatic title forms the first question in the Reading Group Notes and its possible meanings create an undercurrent that surfaces from time to time as one reads…

However, in the case of Patrick Holland’s latest novel One, cover art by the talented Peter Lo gives more than a clue. Nevertheless the significance of the enigmatic title forms the first question in the Reading Group Notes and its possible meanings create an undercurrent that surfaces from time to time as one reads…

‘One’ is both a number, and a pronoun. It’s not just the lowest cardinal number, alluding perhaps to ‘one against the world’, it’s also half of two. So it can draw attention to duality in an individual – an alter ego, a second self, a Jekyll and Hyde, or good and evil in the same character. ‘One’ can also focus the mind on the interdependence of two characters, being two sides of the one coin. Among numerous other meanings, ‘one’ can also mean ‘the same’, or ‘identical’ (as in ‘there’s only one’), and it can mean ‘one amongst many’ suggesting perhaps that in one gang, there may be only one man that matters). And as a pronoun, again amongst other meanings, it can also refer to a person representing people in general, an impersonal pronoun as used in the last sentence of my previous paragraph. This usage is becoming less common in Australia, and sometimes derided as pretentious, but IMO it’s a handy way to focus away from the individual ‘I’ or ‘you’. Then again, in the context of Holland’s novel, set at the turn of the twentieth century when Australia federated to become one country instead of a jigsaw of squabbling colonies, ‘one’ can have an ironic undertone about the unity – the ‘oneness’ – of the emerging nation: its indigenous people weren’t included in the vote and as shown in this book, they were treated as Other rather than as The First Nations among One. My guess is that book groups could spend quite a bit of time pondering this title!

Ostensibly, Holland’s ‘One’ is a tale about bushrangers. The Kenniff brothers, James and Patrick, were Australia’s last bushrangers, running an extensive horse-stealing operation in outback Queensland at the turn of the twentieth century. But One is less of a ‘chase’ narrative and more of a meditation on law and what it means to us as a society. Nixon, a policeman in pursuit of the Kenniffs, doesn’t get much in the way of support from the sparse communities where the bushrangers operate: some don’t help because they fear reprisals; some don’t help because they don’t share the idea of law and order underpinning societies of any kind, much less theirs; and some don’t help because they would rather turn a blind eye:

Thurlow shrugged.

‘Nothin to do with me.’

‘But it is, Tom. Crime undermines every good thing in the world. Even things that criminals, let alone you, regard as good. There must be things in this world you love. Whose sanctity you would preserve from lawlessness.’

Tom Thurlow smiled.

‘Indeed there are, Sergeant, and if, as you say, there are outlaws abroad in the ranges, then let me return to the care of those things. (p.75)

Some of those good things are valued by the bushrangers themselves. Paddy (Patrick) begins to tire of the life:

Paddy only stared into the fire and nodded. Jim saw it.

‘But you look troubled, brother.’

‘I’m tired, Jim. That’s all.

‘Speak.’

‘It’s nothing.’

‘Say it.’

Paddy sighed. He looked at the fire. Then down at his boots.

‘All I want’s a stretch of country. Enough to run a few cattle. So I can break horses for the neighbours and run the cattle I own and that be it. I want a wife.’ (p. 73)

These two brief exchanges show two things I really like about Holland’s writing. There’s the spare prose, not a word wasted, especially in dialogue. The silences evoke both chasms in understanding between people and also the vast emptiness of the Australian outback. The reader never loses the sense of the landscape as indifferent, impervious to the fate of the puny beings who traverse it. There’s also Holland’s interest in people losing sight of what’s really important to them as they blunder around in pursuit of other ambitions.

At 365 pages, it’s quite a long book, one which takes the reader on a journey of introspection. As the story moves across remote parts of Queensland, the pursued become the pursuers, a refuge becomes a prison, and trust becomes a commodity more important even than water in the desert. The vulnerability of the characters is quite harrowing, and the entrapment of youths, women and Aborigines in this lawless society leads to invidious choices. Holland is very good indeed at creating sickening tension:

They crouched and made their way to the edge of the cold camp where the horse was.

Alex stood and put his revolver in his belt. He untied the Babbiloora horse while Elden stood cover with his shotgun pointed at the Skillington boy.

His horse stirred and the boy woke. Eyes opened wide.

Elden put his finger to his lip. He aimed the shotgun at the boy’s face.

Alex nodded at the camp where the men were asleep and whispered.

‘You can keep our friend. We only want the horse.’

The Skillington boy made to speak and Elden locked the bolt on the shotgun.

‘We only want the horse,’ Alex whispered. ‘That’s not worth dying over. Your boss is drunk. You stay right there quiet as a mouse and he’ll never know the difference. When we’re gone, you give us an hour. If we hear you after us, we’ll set an ambush and you’ll die then too.’

‘We’ll shoot all these,’ said Elden. ‘But we’ll wire you to a tree and burn you.’

Alex whispered to Elden.

‘What’s the black boy doing?’

Elden looked across the ashes of the fire at King Edward who stared at him unflinching. He kept his gun trained on the Skillington boy and his eyes on the black boy and spoke to Alex. (p.89)

White settlers had been in Australia for over a century by the time of this novel’s setting, yet the world Holland creates in One is a frontier society. Colonisation is still violent, and the impact on the indigenous people is horrific. The law that is being superimposed over ancient customary law is remote and largely irrelevant in places where there is no consensus about its value or its implementation. There is poverty, extreme hardship and savage cruelty. Mercenaries do unspeakable things to get the reward for the wanted men, and they’re not too fussy about getting identity right. Justice, when it comes, is ambiguous at best.

It sounds raw and confronting, but One is a thoughtful novel that begs the question: what is the law and what makes it work so that people can feel safe and secure in their lives? And also, what can society offer to support those who are ready to choose repentance and rehabilitation?

Author: Patrick Holland

Title: One

Publisher: Transit Lounge, 2016

ISBN: 9781921924965

Review copy courtesy of Transit Lounge

Available from Fishpond: One or direct from Transit Lounge (who BTW have a classy new, much more user friendly website.)

I understand your point about the rule of law, but do you think this 21st century novel adds anything to our understanding of late 19th century Australia? Of course, on the other hand, outback Qld, NSW, WA are still frontier societies, still engaged in wresting land from its rightful owners.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on April 15, 2016

at 9:18 am

Yes, I think it does… ‘One’ is one of those books that lingers after reading, and I’ve been thinking about it on and off as I’ve pottered around the house. (Nursing my wounded shoulder has given me plenty of time for looking at things that need to be done, rather than doing them. My poor vegie patch!)

So I’ve been thinking about what kind of society those people thought they were building. In this book, these were people born here, and what they knew of a settled ‘orderly’ society was second-hand, coloured by their parents’ or grandparents’ memories of British law and justice. Analogous to second generation migrants now, who have rose-coloured or very negative out-of-date ideas about the place their parents came from, calling themselves Greek or Croatian or Vietnamese, as if they were, even though they themselves have never been there.

In the struggle for survival, these turn-of-the-century people (in this book) seemed to have no expectation that there was a viable system for protecting them and that they had a part to play in it. If someone stole their horses or burnt their cottage to the ground, or brutally murdered someone, it was a case of too bad. If you had power like the bushrangers did you could get revenge, if not, bad luck. A policeman on a quest to put a stop to it was a rarity, and he could not expect to get anything much in the way of official resources to help.

These people are not-too-distant ancestors, part of our mythology now, and I’m considering the extent to which their attitudes persist today…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 15, 2016

at 10:13 am

My grandparents’ parents were Queenslanders of this time, mostly on the coast though one was gold warden in Charters Towers – he was the law! I’m planning to review Rosa Praed whose family were from mid 19th century Qld and were involved in a famous massacre. Hopefully from there I can make comparisons.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on April 15, 2016

at 10:54 am

PS I would really, really like you to read this book. I want to know what you think of it!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 15, 2016

at 10:14 am

I will try to read this and come back and read your review then. The cover is intriguing! And I haven’t read Holland before.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on April 15, 2016

at 10:32 am

Oh yes, I want you to read this too! (Never read Holland? you are in for a treat!)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 15, 2016

at 10:35 am

Too many books, too little time for reading!

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on April 15, 2016

at 10:57 am

Amen to that. But do make time for this one, I think you will really love it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 15, 2016

at 11:17 am

I’ve never given that much thought to the various ways in which one can understand the word “one” but as yoy say that does give rise to some potentially rich discussions about its meaning in this novel.

LikeLike

By: BookerTalk on April 15, 2016

at 10:58 am

LOL I’d never thought about it either. I mean, ‘one’ we just use it, don’t we? But that’s the point about reading, it pushes us into thinking about things we’ve never thought much about before:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 15, 2016

at 11:18 am

Sold! Except it’s not available here yet… It sounds fab.

LikeLike

By: kimbofo on April 15, 2016

at 6:28 pm

It is just your kind of book, Kim:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 15, 2016

at 6:39 pm

[…] One by Patrick Holland, see my review […]

LikeLike

By: 2017 Miles Franklin Award longlist | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on May 2, 2017

at 6:27 pm

[…] by Patrick Holland, see my review and Patrick’s explanation for his curious choice of […]

LikeLike

By: Aussie and Kiwi authors on the 2018 Dublin Literary Award Longlist | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 9, 2017

at 9:34 am