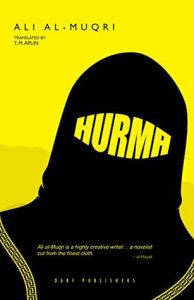

Hurma is another book that I came across thanks to a review by Stu at Winston’s Dad, and it’s the first I’ve ever read by a Yemeni author. Wikipedia tells me that Yemen is a developing country, and the poorest country in the Middle East. It is isolated amongst its neighbours because it refused to support the First Gulf War to liberate Kuwait from Saddam Hussein. Governance and corruption have been major problems there for ages and a civil war in the 1990s was never really resolved – rebel forces took the country’s capital in 2015. Given this state of affairs, it seems amazing that there is a functioning publishing industry, but again Wikipedia comes to the rescue with a page about Ali Al-Muqri which tells me that his work is published in a magazine called Banipal, and that two of his books have been nominated for the Arab Booker Prize. (A prize apparently organised from London and funded by Emirates, with the aim of promoting good quality Arab literature).

Hurma is another book that I came across thanks to a review by Stu at Winston’s Dad, and it’s the first I’ve ever read by a Yemeni author. Wikipedia tells me that Yemen is a developing country, and the poorest country in the Middle East. It is isolated amongst its neighbours because it refused to support the First Gulf War to liberate Kuwait from Saddam Hussein. Governance and corruption have been major problems there for ages and a civil war in the 1990s was never really resolved – rebel forces took the country’s capital in 2015. Given this state of affairs, it seems amazing that there is a functioning publishing industry, but again Wikipedia comes to the rescue with a page about Ali Al-Muqri which tells me that his work is published in a magazine called Banipal, and that two of his books have been nominated for the Arab Booker Prize. (A prize apparently organised from London and funded by Emirates, with the aim of promoting good quality Arab literature).

Now, courtesy of the Brisbane Writers Festival Opening Address, there’s a been a brouhaha about writers appropriating the culture and experiences of others, and I do not want to get into that*. But this book (like The Patience Stone) is written by a male author purporting to be a woman under the veil. Written in a culture that oppresses women, this novella gives a voice to the silent and the invisible. Yes, it would be better if there were a flourishing Yemeni publishing industry that brought us both male and female authors who could write freely about taboo subjects, but from what I’ve been able to glean from Wikipedia, Ali Al-Muqri is lionised in the west because he has the courage to tackle taboos like sex, religion and war. So… while I wait for translations from the emerging women’s writing industry in Yemen, I’m reading Hurma…

‘Hurma’ means ‘sanctity’ and the nameless woman who narrates this strange and alienating tale is just another anonymous woman shrouded in black who must be protected from violation or dishonour. She grows up in an ultra-conservative society where not even her voice may be heard outside the home because it is ‘haram’ i.e. forbidden. But she has a lively and spirited sister called Lula who gets hold of pornographic cassette tapes, and who is allowed more freedom than is normal because her father is indebted to her for his life. ‘Hurma’ learns about sex (at least in theory) from Lula, and also from a lascivious lecturer at the Islamic University who (via a video link, since he cannot be in the same room with the women) explains how matters of sex in the Koran should be interpreted. The hypocrisy of his words is exposed when the camera strays south of his waistband and the girls can see what he is doing…

Women reading this book will feel a sense of claustrophobia at the limitations of life in this society. Marriages are arranged with total strangers, and the ridiculousness of the rules is satirised in a television debate about whether a woman can circumvent the rules about being with strange men by suckling them (having the effect of making them family).

I was surprised by the bluntness of some of the viewers’ questions. If they hadn’t cited verses from the Quran and the words of the Prophet – peace be upon him – I might have doubted their Islam. One viewer said in astonishment, ‘God bless our venerable sheikh who has shown us that sharia can solve any problem, including the mixing of the sexes.’ The second caller agreed with the first and said she would breastfeed her male colleagues at work so she could mix with them without feeling sinful, something that had really been bothering her.

One of the callers thought the fatwa was wonderful but wondered how she could suckle the family’s Ethiopian driver and make him family, given that he was Christian? (p. 101)

That these rules are all about having power over women in a patriarchal society is shown by the transformation of ‘Hurma’s’ brother from a socialist sympathiser who has no time for religion to a proselytising husband constantly practising sermons to inflict on the female members of his family. The transformation comes about when he accidently sees the face of Nura, falls passionately in love with her, and then finds that religion is the way to manage his jealousy and possessiveness. Under the form of Islam available to him in Yemen, he can have absolute control over her and every aspect of her life.

Things take a more serious turn when ‘Hurma’ is manipulated into jihad by her strange husband. The book shows that in situations like this, the notion of being ‘radicalised’ is a nonsense. ‘Hurma’ has no idea why she is wanted, what her role might be, or what the purpose of her actions are. She is asked to research newspapers publishing taboo subjects in the newspaper, and to spy on people who might be breaching Islamic law, but she doesn’t know what the consequences might be when she writes her report. Eventually – completely ignorant of any politics except a generalised hatred of the Wicked West – she is whisked off to Afghanistan where the rape of women is commonplace but the victims cannot even talk about it amongst women afterwards. For ‘Hurma’, whose husband is impotent, her curiosity and ignorance about sex takes an alienating turn when she wonders about the possibility of rape as a cure for her frustration. I do not think a female author would have contemplated such a possibility…

Hurma is a somewhat disjointed book, where the reader like the nameless narrator does not have all the information needed to make sense of things. There are lots of quotations of ‘hadith’ (religious teachings describing the words, actions, or habits of the Islamic prophet Muhammad) but although they are footnoted, non-Muslims cannot know whether they are genuine or out of context, or not. Not having been to Yemen (and with no plans to go!) I cannot know how accurate a depiction of Yemeni life for women this novel might be, and as Geraldine Brooks showed in Nine Parts of Desire a casual visitor is unlikely to find out in ultraconservative societies where women are silent and invisible. So I am acutely aware that I read this book differently from the way a Yemeni woman would read it, or a Muslim woman in the West. However, the impression I get is that the form of Islam being depicted in Hurma is an aberration and that Yemen is a society that is using religion as a way of maintaining a patriarchal society. Because I grew into womanhood during the 1970s when in the West women were starting to take their rightful place in society, it seems unbelievably sad that the Middle East is still riddled with societies like this, almost half a century later.

There is an interview with the author at Qantara, and a thoughtful review at Globally Curious.

*I’m sorry, I can’t find a link to what was actually said by Lionel Shriver, only to a critic of it who walked out and didn’t hear all of what was said. So I don’t know what Shriver was on about or the context, and including a one-sided link here doesn’t look fair to me. So if you are interested, you’ll have to do your own search.

Author: Ali Al-Muqri

Title: Hurma

Translated by T.M.Aplin

Publisher: Darf Publishers, London, 2015, first published 2012

ISBN: 9781850772774

Source: Personal library, purchased from Fishpond $14.84

Available from Fishpond:Hurma

Firstly re Shriver, Kate W saw her in Melb and reported here: https://booksaremyfavouriteandbest.wordpress.com/2016/09/06/lionel-shriver-at-the-melbourne-writers-festival/#more-12018

I plead guilty to putting up a link (on my facebook a/c) to the Shriver critic who walked out – I thought she had some interesting things to say, that I agreed with.

I know you were uncomfortable with this book being by a male author – I think that if I were going to read a book about Muslim women I might start with, say, a Bengali woman author.

Australian author Eva Sallis studied in Yemen, but I don’t think she wrote about it.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on September 11, 2016

at 3:41 pm

No need to plead guilty, my friend, but why can’t I find a media report of what Shriver actually said? (Kate’s post is wonderful, but it doesn’t explain anything that seems contentious to me).

IMO if it’s good enough for The Guardian to give airspace to the critic, why can’t we also see Shriver’s PoV and make up our own minds? It’s most peculiar and for those of us who weren’t there it begins to look like a publicity stunt by the indignant young critic.

That’s interesting about Sallis, LOL maybe she feels that writing about it would be ‘appropriation’… but then, she wrote about a feral child in Russia in Dog Boy…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 11, 2016

at 4:03 pm

Yes, the Guardian piece was written as though ‘everyone’ knew Shriver’s pov. A link, even to a prior essay, would have been handy, it’s an interesting and topical debate.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on September 11, 2016

at 6:03 pm

Exactly!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 11, 2016

at 7:01 pm

I nearly bought this book earlier this year but held back, something is telling me that I will not get along with it. I can’t really pinpoint why, maybe it is the disjointedness of it…

LikeLike

By: Sharkelly on September 11, 2016

at 8:42 pm

Go with your instincts…life is too short to read books that don’t appeal:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 11, 2016

at 9:37 pm

Wonderful review, Lisa! This looks like an interesting book. I have never heard of this writer before and I also didn’t know that Yemen was so conservative. I sometimes find that a literary work loses a lot of power when it is translated, especially into a language which is culturally very different. For example a character might do something which will be regarded as a huge act of rebellion by readers in the original language and leave a huge emotional impact, but when that book is translated into another culturally different language, it might not look that way, or have the same emotional impact. I think that might be one of the problems with this book – it might have had a huge impact among its original readers, but doesn’t have the same impact, when translated. What do you think? I also found this line on your post very interesting – “there’s a been a brouhaha about writers appropriating the culture and experiences of others”. It is interesting, because one of my writer friends was telling me that her publisher told her that she cannot have POC (Person of Colour) characters in her book as she was not POC and so readers won’t accept it as they would find it inauthentic. I have mixed feelings about it. If a writer can write only about people who are like her / him, then what is the fun in that? And where do we draw the line? Can a man write about a woman? Can a woman write about a man? Can a grown-up write about a child? If we really take it to the extreme, everything will start looking inauthentic, isn’t it? What do you think?

LikeLike

By: Vishy on September 12, 2016

at 6:22 am

I think it’s a very hard question! I’m open to hearing more of the arguments about it, but I haven’t made up my mind yet, though I think I tend more towards openness than closing things up.

I would really like to see this issue treated by one or other of the philosophers that I read, like Peter Singer or Damon Young.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on September 12, 2016

at 8:58 am

[…] Hurma by Ali Al-Muqri (via ANZ Litlovers) […]

LikeLike

By: It’s Monday and I’ve just finished Akata Witch | Real Life Reading on September 13, 2016

at 12:05 am