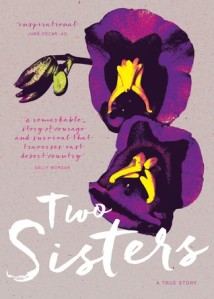

Two Sisters is a riveting book, one that deserves a wide audience.

Two Sisters is a riveting book, one that deserves a wide audience.

This is the blurb from Magabala Books that made me want to read the book:

Ngarta and Jukuna lived in the Great Sandy Desert. They traversed country according to the seasons, just as the Walmajarri people had done for thousands of years. But it was a time of change. Desert people who had lived with little knowledge of European settlement were now moving onto cattle stations. Those left behind were vulnerable and faced unimaginable challenges.

In 1961, when Jukuna leaves with her new husband, young Ngarta remains with a group of women and children. Tragedy strikes and Ngarta is forced to travel alone. Her survival depends on cunning and courage as she is pursued by two murderers in a vast unforgiving landscape.

Jukuna’s rich account may be the first autobiography written in an Aboriginal language. Presented in English and Walmajarri, her determination to see her language written has made her one of our most valued authors.

I have read a few books by desert people, but I haven’t read one like this. It is hard to convey the sense of wonder with which I read it. Two Sisters is an authentic account of an ancient way of life as it was lived by sisters Ngarta and Jukuna in the Great Sandy Desert, and then it covers the period when this way of life was disrupted by the coming of Europeans into the north. It is written by people who had never seen a white person or any of the accoutrements of station life, so much so that when they encounter a water tank, their first action is to placate the water spirit that they believe inhabits all the water holes that sustain them. But theirs is not a life of deficits: they led a rich, fulfilling life, learning skills of more than mere survival since childhood, and supported by a kinship system which ensured that there was always family to take care of them. It was only when this life was disrupted that there were not enough men around to enforce the law and keep everyone safe, but even then the habits of resilience and independence stand the sisters in good stead.

When I read about the teenage Ngarta taking off alone across the desert, I was stunned.

Ngarta lived in terror of the two men. She had seen them spear her mother and kill her grandmother and then her brother for no reason at all. She kept wondering who would be next. When she had the chance, she took her mother to one side. ‘I said to my mother:’ “You and me’ll have to go, run away in the night. They might kill us.” But my mother wouldn’t listen.’ Perhaps Ngarta’s mother was too frightened to run away. in case the men followed them. She must have wondered where else she and her daughter could go, when their only remaining relatives were here in this last little band. Ngarta made up her mind to go on her own.

The next afternoon, when the brothers were out of sight, Ngarta ran away.

‘So I went away on my own, in the afternoon. I went west. I took only a kana [digging stick] for hunting and a firestick. I walked on the grass all the way, till I got to Jarirri. ‘ Instead of walking on the sand, Ngarta stepped from one tuft of spinifex to another in order to leave no footprints. (p.39)

For a year, she lived on her own in the desert:

Ngarta visited other waterholes she knew, spending time at each one, living by hunting and collecting fruits from the trees and plants and seeds from the grasses. All the time she was heading in a northerly direction. In due course she made her way to the big jumu, [a soak, a temporary source of underground water] Kajamuka.

Ngarta had never left her desert country, but she thought she knew how to get to Christmas Creek Station. Her various relatives who had travelled back and forth between the desert and the station had described the journey to her. She had heard people talking about the direction of the waterholes they stopped at on the way, and she had a good idea of how to find them. Besides that, it was wet weather time again, and there should be enough rain falling to keep her out of trouble should she miss one of them. (p.40)

This journey has the same epic quality as Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington.

Equally impressive is Jukuna’s determination to ensure that the Walmajarri language isn’t lost.

Over the years I have done a lot of work related to my language, Walmajarri. I learned to read Walmajarri and I have learned to write it too. With other people I translated some parts of God’s word from English into Walmajarri. We carefully checked that work, then I read some of the translation onto cassettes. Those cassettes were sold to others so that they could hear God’s word.

Another thing I did was teach some white people to speak a little Walmajarri. Later on I went to the adult education centre in Fitzroy Crossing, called Karrayili. There I began to learn English – writing and reading it, recognising the letters and words. [….] Now I teach children Walmajarri, and I really enjoy doing it. I teach them how to find bush foods and animals, and I teach them the names of the animals that live in the river country and that big goanna that belongs to the plains country. I also tech the children the names of other, smaller animals. (p.79)

The book comprises just 125 pages which consist of

- Ngarta’s story – a desert tragedy

- Jukuna’s story – my life in the desert

- Wangki Ngajukura Jiljingajangka (Jukuna’s story in Walmajarri)

- Short explanatory pieces by Pat Lowe

- The Walmajarri diaspora

- The world of the two sisters

- Working with Ngarta

- A short explanatory piece by Eirlys Richards

- Working with Jukuna, and

- A Wanmajarri pronunciation guide and a glossary

There are also full colour photos of beautiful art works by Ngarta and Jukuna, and photos of the sisters on country in the Great Sandy Desert, a vivid reminder of the world that the sisters lived in.

Its format makes it an ideal book to use with secondary school students wanting to learn more about indigenous lifestyles prior to European settlement.

Weezelle has also reviewed it too.

Authors: Ngarta (Ngarta Jinny Bent); Jukuna (Jukuna Mona Chuguna); Pat Lowe and Eirlys Richards

Title: Two Sisters, a true story

Publisher: Magabala Books, 2016

ISBN: 9781925360271

Review copy courtesy of Magabala Books

Available from Fishpond (Two Sisters: A True Story) and direct from Magabala Books.

Lisa thank you for sharing such an amazing story – how wonderful if schools do take your advice and students get access to this first-hand account of the meeting of cultures and not only the survival of the sisters but their determination to keep the Walmajarri language and bushcraft alive .

LikeLike

By: mairineilcreative writer on September 15, 2016

at 11:22 pm

It’s books like this that make me feel a little bit tempted to resurrect my LisaHillSchoolStuff blog (because lots of people still read it even though I ‘retired it’ nearly two years ago) – but so far, I haven’t succumbed!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 15, 2016

at 11:39 pm

Definitely a must buy. There is a Christmas Creek next door to Roy Hill, not far from Jigalong where the Rabbit proof fence girls were from, though this sounds as though they were further north. Anyway I’ll read it and find out.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on September 15, 2016

at 11:40 pm

Two Sisters seems like a engaging memoir. The explanatory notes and language glossary are important additions to the memoir. I hope that schools would incorporate Ngarta and Jukuna’s personal narratives into their reading and social studies curriculums.

There is an Aboriginal author name Dylan Coleman who won the David Unaipon award for her novel, Mazin Grace. Included with the story is a glossary of language glossary.

Including the language glossary in addition to authentic aboriginal narratives is a work of cultural preservation as well as an act of social and political autonomy.

LikeLike

By: smaxine27 on September 28, 2016

at 12:12 pm

Yes, I read Mazin Grace (https://anzlitlovers.com/2012/12/22/mazin-grace-by-dylan-coleman/) and found the glossary useful.

But I have read that (as always these days) there is a different PoV about glossaries. From memory, the argument is that dominant cultures don’t use them: readers are expected to work out words they don’t know for themselves, and, by implication, absorb these new words as part of their vocabulary. So from that PoV submitting to the demand for a glossary implies accepting an inferior place in the hierarchy of languages and cultures and making it easy for the dominant culture to ignore the language that has been deliberately chosen for its specific meaning and that the author has carefully placed so that its meaning can be deduced from context.

As it happens, I’ve been reading a play called Barungin, by Jack Davis, and it is littered with Noongar words (from Southern WA). But even though there is a glossary in the edition I have, each word can be deduced from context, and since it’s a play, that’s essential because the audience wouldn’t have a glossary.

I think the necessity for a glossary may depend a bit on whether the language is endangered, as many indigenous languages are.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 28, 2016

at 1:02 pm

I’ve just finished reading Two Sisters and am poised to write a review – it’s great to see that others are reading this and profiling it. Unlike you, I’m really new to this kind of narrative, so it was interesting to read your opinion when you clearly have other examples to compare it with.

LikeLike

By: Weezelle on October 9, 2016

at 4:27 pm

Hello, and thank you for dropping by to comment.

I would say that we are all on a long journey when it comes to reading indigenous stories, and we are all at different starting points. I try to read as much indigenous literature as I can from varying PoVs, but I find that there is always another perspective that I hadn’t known about. Yesterday I went to a workshop exploring the possibility of reviving old plays from the Australian repertoire, and this time it was about Jack Davis’s compelling play Barangin, Smell the Wind. Amongst other things in this workshop, I learned that LOL the most opinionated views can came from where you least expect it: someone who had worked in a community and who felt it was time for our indigenous people to ‘move on’. Not an opinion I think non-indigenous people are entitled to have, since there is very little in the way of restorative justice happening, and even if it is, there’s no obligation on the people who’ve been wronged to accept it and ‘move on’.

I’m reading Larissa Behrendt’s Finding Eliza, Power and colonial storytelling at the moment. I hope to have a review up about that soon too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on October 9, 2016

at 4:56 pm

That’s great that you’ve been dedicated so much time to reading indigenous literature. I’ve lived abroad for the last decade, so I’ve come home and am now realising how much I’ve missed out on. Are there any books in particular you’d recommend.

I look forward to reading your review of Finding Eliza.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Weezelle on October 9, 2016

at 10:18 pm

There are heaps of reviews and recommended titles in my Indigenous Reading List in the top menu: each year when I host Indigenous Lit Week readers join in and I collate all the reviews and add them to the list. But for starters I would begin with Am I Black Enough for You by Anita Heiss, and That Deadman Dance by Kim Scott, and Mullumbimby by Melissa Lucashenko.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 10, 2016

at 12:04 am

Thanks for these. I’ve heard of the first and the last book, but not the second. I will request them from the library forthwith!

LikeLike

By: Weezelle on October 10, 2016

at 9:02 pm

Enjoy!

PS I’ve just this minute uploaded my review of Finding Eliza:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on October 10, 2016

at 9:09 pm

I’ll check it out…

LikeLike

By: Weezelle on October 10, 2016

at 11:25 pm

[…] Lisa at ANZLL’s review (here) […]

LikeLike

By: Two Sisters, Ngarta and Jukuna | theaustralianlegend on October 21, 2016

at 10:33 am

Hi Lisa, a bit late but I have just read the Two Sisters, and as you say in your review it leaves one in wonder. A fascinating read, and I feel gained some insight into Jukuna’s and Ngarta lives.They were such strong women. I did appreciate the glossary for the Aboriginal words and the photos of the desert and paintings. I think it would be an excellent book to have in a school library.

LikeLike

By: Meg on July 26, 2018

at 8:12 pm

Not late at all, Meg, I keep this ‘week’ going for all of July:)

It’s an amazing book … you know how you read about solitary confinement and its effects on mental health, and here’s a mere slip of a girl living alone in the desert for a whole year. Just amazing…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on July 26, 2018

at 8:32 pm

[…] (see her comment […]

LikeLike

By: Wrapping up Indigenous Literature Week 2018 at ANZ LitLovers | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on July 26, 2018

at 8:35 pm

[…] see Meg’s thoughts in her comment here […]

LikeLike

By: Reviews from Indigenous Literature Week at ANZ Litlovers 2018 | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on July 26, 2018

at 8:35 pm

[…] see my ANZ LitLovers review […]

LikeLike

By: 2018 Indigenous Literature Week – a Reading List of Indigenous Women Writers | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on June 5, 2019

at 11:30 am

[…] see my ANZ LitLovers review […]

LikeLike

By: Indigenous Literature Week – a Reading List of Indigenous Women Writers | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on June 5, 2019

at 11:34 am

[…] of ANZLitLovers liked this one too — read her review here. Bill, who blogs at The Australian Legend, has also reviewed […]

LikeLike

By: ‘Two Sisters: Ngarta and Jukuna’ by Ngarta Jinny Bent, Jukuna Mona Chuguna, Pat Lowe & Eirlys Richards – Reading Matters on January 27, 2020

at 12:40 am