Christina Stead Week (November 14-20, 2016)

It’s not easy to explain how much pleasure there was in reading Christina Stead’s second novel The Beauties and Furies, (1936), published by Peter Davies, London in 1936. It is such a dynamic novel, rich with wonderfully complex characters and a compelling storyline, and all through it there are little surprises alluding to contemporary political events, which remind us that Europe was becoming alarmed about the rise of fascism.

As can be seen from the Opening Lines which I posted last week, the novel is set in Paris, and now that I’ve read the book, I know that those lines introduce the curious triangle of characters who dominate the action of the novel. The young woman on her way to Paris is Elvira Western, abandoning her husband in London to meet her lover Oliver Fenton, a student of socialism. The Italian gentleman is the villain of the piece, a Machiavellian pseudo-sorcerer, who interferes in the lives of others for the amusement of it. Elvira doesn’t know it yet, but he is going to cause all sorts of trouble…

The reader, however, knows from the very first chapter that the relationship with Oliver is doomed, and that is because Elvira exhibits signs of irritation and boredom already. Oliver is very interested in politics, but she’s not. She gets a crick in her neck from resting her head on his shoulder. She keeps mentioning her husband, and she smiles at Oliver’s vanity. And she bristles when he starts trying to remake her to suit Paris:

‘You’re beautiful,’ he said, but you don’t know how to dress. A French woman built like you would build up her bosom. I’ll take you to a dressmaker who will study your style and bring out your femininity. You kust go, the very first thing, to the Printemps, or to Antoine, and have your hair done too. Oh, you’ll spend fortunes on yourself before you’ve been in Paris long. You’ll be quite a different woman. You can dress, you know. You’ll be splendid when you’re dressed like a French woman. Everyone will say, How adaptable she is.’

She gave him a long surprised look and began to laugh.

‘Oliver, so I don’t suit you? You brought me over to make me a French woman. You’re an incredible chauvinist.’ (p. 13-14)

He doesn’t get the message:

‘No cracks: I’m going to boss you from now on. You’re going to find out what you’ve been missing all your life. You’ve been a nice lady: I’m going to make you into a grand girl.’

She laughed. ‘Dress doesn’t suit, airs don’t suit; thanks very much. What a terrible fellow you are! Do you think you’ll recognise me when you’ve finished making me over?’ (p.15)

Perhaps there are autobiographical elements in this little exchange? It has an uncanny ring of truth…

Elvira’s sardonic amusement changes to anger when that fool Marpurgo (who has smoothly attached himself to the duo in no time at all) demands from the hotel staff a Marxist newspaper (just to annoy them) and Oliver produces his copy of it from their hotel room upstairs. She rejects with her habitual quiet disdain the Parisian life busily frittered away, and she ticks Oliver off when he says he likes to hear a woman play the piano about the house:

‘A woman is a human being, not an aesthetic gratification.’

By the time she is mocking Oliver’s effrontery with women, I was liking Elvira very much, remembering from decades ago my own skirmishes with men who tried to patronise and diminish me with chauvinistic nonsense. And I retained that fondness for Elvira even though she is an exasperating creation, dithering about which man ultimately to choose, and surrendering to jealousy when Marpurgo engineers a meeting with a woman who has tempted the wayward Oliver’s interest.

Coromandel, on the other hand, reacts with aplomb. Like Blanche, a young prostitute befriended by Elvira, she has the career denied to Elvira by her early marriage. Coromandel might be attracted to Oliver (who is unreasonably attractive) but she does not need a man to give her a sense of identity, and neither does Blanche. These women live life on their own terms. I kept having to remind myself that Stead wrote this book in the 1930s, long before the women’s liberation movement.

But as well as painting a vivid portrait of Parisian café society, Stead also depicts the political and economic undercurrents that were brewing trouble for Europe and the world. Here and there the reader sees glimpses of Depression era poverty, and there is commentary about how the possessions of middle-class people have lost value in the new pauper economy. Business people are at risk too. Coromandel’s father is an antique-dealer with a nostalgia for exquisite hand-made lace but customers are few and far between; while Marpurgo’s employers are anxious about his extravagant expense account and plotting a scurrilous scheme to prop up the business on the stock exchange. Disaster is coming but people in the know have plans afoot to get to Patagonia or Iles D’Or or Australia (i.e. the ends of the earth!)

Oliver is a student of socialism, but his enthusiasm is only in the abstract. He is what we would call today a ‘chardonnay socialist’. Elvira is more honest: on a visit to Fontainebleau she tells Oliver that she would hate the socialist dreams of a planned city, because she loves the grand extravagance of the rowdy centuries. She tells Oliver to ease up on his political activities, she is beginning to be afraid that they might cause trouble, but she is also sick of being preached to. He promises to stop being her Messiah – but only for a while.

Well, birth control being what it was in the 1930s, the inevitable happens, and this brings all sorts of issues to the surface. Elvira has an independent income of two hundred pounds a year, but Oliver has nothing – and Elvira has not lost her taste for expensive linens not to mention the extravagances of café society. More importantly, she had left Paul because, with an MA from Oxford, she had wanted an intellectual life, with the opportunity to do something creative, perhaps writing…

The Beauties and Furies is a brilliant novel. It’s my favourite so far!

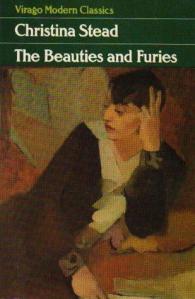

Author: Christina Stead

Title: The Beauties and Furies

Introduction by Hilary Bailey

Publisher: Virago Modern Classics, 1982

ISBN 0860681750

Cover image: detail from ‘Portrait of Lucy Beynis’ by Grace Cowley, (held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales)

If you like the sound of this, I have a Text Classics copy (with an introduction by Margaret Harris) to give away to readers with an Australian postcode. Please indicate your interest in the comments below. Then keep an eye out for the announcement of the winner either here or @anzlitlovers on Twitter so that you can get back to me with an address for posting. I’ll draw the winner for this one quickly, during Christina Stead Week.

If you like the sound of this, I have a Text Classics copy (with an introduction by Margaret Harris) to give away to readers with an Australian postcode. Please indicate your interest in the comments below. Then keep an eye out for the announcement of the winner either here or @anzlitlovers on Twitter so that you can get back to me with an address for posting. I’ll draw the winner for this one quickly, during Christina Stead Week.

I’d really love a copy of this. Thanks, Claire.

LikeLike

By: clairethomaswriter on November 15, 2016

at 10:09 am

Good luck, Claire!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 15, 2016

at 4:06 pm

I’ve been enjoying the opening lines for Stead’s books – which one will you be reading all the way through?

My first thoughts on The Salzburg Tales are here – http://bronasbooks.blogspot.com.au/2016/11/bronas-salon.html

LikeLike

By: Brona on November 15, 2016

at 10:15 am

Thanks, Brona, I’ll add it to the master list. (I’ve just finished The Beauties and Furies, my review went up today).

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on November 15, 2016

at 4:06 pm

Hi Brona, I’ve just read your post (but *frown, blogspot* have to comment here) and I do like the way you’ve written about it. I just looked up TST in the Stead bio and it says it features

‘delight in irony, heaping up of detail and imagery, the exorbitant lists, the love of parody’.

So no wonder it’s not exactly bedtime reading!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 16, 2016

at 8:10 am

Stead’s big love interest, apart from Bill Blake, was Ralph Fox (Harry Girton in For Love Alone). The Chris Williams biog mentions a couple of abortions/miscarriages but I skipped over them in my review. I don’t want to argue feminist theory but womens lib built on 60 or 70 years of first wave feminism of which Stead was obviously part.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on November 15, 2016

at 10:51 am

Phew, *chuckle* I’d be right out of my depth with feminist theory… but I had to comment on it here because (while hardly an expert on OzLit of the 1930s) I haven’t found much in the way of explicit skirmishes as in this book….

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 15, 2016

at 4:09 pm

I have a review copy of this but it’s not due to be published until next year. Looking forward to it.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on November 15, 2016

at 12:43 pm

Who is the publisher?

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 15, 2016

at 4:05 pm

TEXT

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on November 16, 2016

at 3:22 am

I am almost finished Seven Poor Men of Sydney and cannot offer enough praise to this amazing writer. This is a third reading and have discovered another layer of her exquisite prose. I cannot decide what would be my favourite book as they are all brilliant. The language, the characters are creations from a special intellect and how fortunate to claim her as one of our own. She was well ahead of her time and a marvellous story teller.

LikeLike

By: Fay Kennedy on November 15, 2016

at 10:10 pm

Yes, indeed, I think that like all classics, her books do repay re-reading:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 15, 2016

at 11:25 pm

Great review Lisa! I have a lovely Virago of this, as you know, and I had considered reading it for this week but ran out of time. But I *will* get to it eventually!

LikeLike

By: kaggsysbookishramblings on November 16, 2016

at 1:39 am

Thanks, Kaggsy, you will love it when you get to it:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on November 16, 2016

at 8:32 am

I note that some of the discussion is leaning towards feminism. Interestingly in the used copy of Ocean of Story I just bought, there’s a newspaper clipping, a letter to the editor, in response to a review. The writer says that she knew Stead and that Stead had no time for feminists.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on November 16, 2016

at 3:24 am

Ooh! That’s something else I’ll have to look up in the bio. Do you know who the writer was? (In my review of Hazel Rowley’s bio (https://anzlitlovers.com/2013/11/22/christina-stead-a-biography-by-hazel-rowley/) I wrote that “she was downright hostile to the women’s movement in the 60s and 70s” so I’ll have to find the bit that made me write that, eh?

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 16, 2016

at 7:57 am

It’s a letter to the editor in response to a review by Jonathan Franzen to the Man Who Loved Children;”she almost closed the door on me when I told her feminists were eager to read her…”

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on November 16, 2016

at 9:47 am

Kate Webb discusses “Stead’s antipathy to the wider Women’s Movement” comprehensively here, if you want a rundown.

LikeLike

By: Pykk on November 20, 2016

at 10:24 am

Thanks for this… it takes a while to read, but it’s very interesting indeed. I’ve always been drawn to power rather than victimhood myself…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on November 20, 2016

at 10:51 am

[…] The Beauties and Furies (1936), see my review […]

LikeLike

By: Literary Influences on Christina Stead (1902-1983) | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 16, 2016

at 10:05 am

[…] I have most recently read Seven Poor Men of Sydney (see my review) and The Beauties and Furies (see my review) there is a clear critique of the economic system and the people who run it. In Chapter 4, […]

LikeLike

By: Modernism, a Very Short Introduction, by Christopher Butler … and Christina Stead | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 17, 2016

at 10:15 am

[…] can be seen from the Opening Lines, and my review, this second novel by Christina Stead is great reading and I hope it sets the winner off on a […]

LikeLike

By: Book giveaway winner: The Beauties and Furies, by Christina Stead | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 20, 2016

at 6:47 pm

[…] read The Beauties and Furies (see here) but I’m ‘saving’ the chapter about Christina Stead until I’ve read House […]

LikeLike

By: Je Suis Australienne, Remarkable Women in France, 1880-1945, by Rosemary Lancaster | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on May 7, 2020

at 9:00 am

[…] Christina Stead’s The beauties and furies (Lisa’s review) […]

LikeLike

By: Monday musings on Australian literature: 1936 in fiction | Whispering Gums on April 5, 2021

at 11:00 pm

Wonderful review Lisa. I thought Stead captured the social and political situation so well, as you describe. It felt grounded in that particular time, but still so much to offer readers now too due to the detailed characterisation.

LikeLike

By: madamebibilophile on May 5, 2021

at 6:23 am

I wasn’t so keen on her most famous book, The Man Who Loved Children, but I liked everything else I’ve read of hers. I still have her chunkster, House of All Nations to read, but I think I need another lockdown to get through it, it’s 1000+ pages.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on May 5, 2021

at 10:50 am