It is many years now since I went through a Blytonesque phase of reading everything – everything! – that my local library had to offer by the 19th century British writer, Anthony Trollope, but I retain an immense fondness for his characters. These days I see them within my mind’s eye in their BBC personas because the Chronicles of Barsetshire and The Pallisers have all been rendered into TV series, but my sense of Trollope’s gentle wisdom about the fallibility of man derives from the words on the page, from all those years ago.

It is many years now since I went through a Blytonesque phase of reading everything – everything! – that my local library had to offer by the 19th century British writer, Anthony Trollope, but I retain an immense fondness for his characters. These days I see them within my mind’s eye in their BBC personas because the Chronicles of Barsetshire and The Pallisers have all been rendered into TV series, but my sense of Trollope’s gentle wisdom about the fallibility of man derives from the words on the page, from all those years ago.

And now, from reading this autobiography I know how Trollope came to be wise about the fallibility of man. He had a terrible childhood and adolescence, he endured middle-class poverty and disappointed expectations, and he became a useless tearaway in his early youth. From his own idle, debt-ridden years he knew what it was to be on the wrong path, and from his administrative work in the Post Office Civil Service, he understood how minor corruption could establish itself uncorrected because people chose not to investigate irregularities. (If you’ve ever seen that episode of Lark Rise to Candleford where Lark Rise residents challenge the rule that the recipient had to pay for the telegram if they’re outside the delivery distance, then you’ll understand why Trollope was out to ensure that there was no profiteering on mail delivery on his watch).

But enchanting as it is to read Trollope’s journey towards becoming a successful novelist, An Autobiography offers more than that, as the Introduction by Nicholas Shrimpton makes clear. Observed by a fellow passenger en route across the Atlantic to be hard at work,

Trollope for once was not busy on a novel. Instead, he was writing An Autobiography.

The result was not only the only autobiography by a major Victorian novelist. It was also a book which has divided opinion ever since. For some, it is one of the truest, most honest autobiographies ever written: an engrossing account of a young man who unexpectedly rescues himself from drift, doubt, and professional failure in his late twenties, and goes on to achieve a happy marriage and a successful career. For others it is a dismayingly philistine account of the life of a professional writer. Preoccupied with contracts, deadlines and earnings, unblushingly explicit about the methods used to achieve success, emotionally reticent, and factually unreliable, it can be seen as a mere memoir, or self-help manual, rather than a genuine exploration of the self. (p. v1)

Oh, I do hope I haven’t put anyone off by placing this paragraph upfront! The book is such good reading! But the introduction goes on to say that the book (published posthumously in accordance with Trollope’s instructions) did his literary reputation no good at all. By making explicit his industrious methods of work, Trollope confronted the theory of ‘inspiration’ and a hovering muse, and demolished it. He got up at 5:30AM every day and wrote his quota of words before going to work. But the critics were not impressed by this revelation. He had been prolific and could now be accused of writing with mere mechanical skill…

I find this attitude baffling. Trollope wrote books that could – a century later – keep a twenty-something reader on the other side of the world utterly absorbed for months and whose adaptations for the screen could captivate a whole new generation of fans. Trollope was not an Enid Blyton or an Agatha Christie, churning out formulaic bestsellers with apparently effortless regularity: he wrote intelligent social novels that exposed the foibles and minor corruption of the clergy and landed gentry. As I indicated in the Sensational Snippet I posted a day or so ago, his forty-seven novels explored political, social, and gender issues in realistic detail.

Did the disdainful critics not understand that the industrious Trollope was following the model of his mother Frances Milton Trollope who picked up her pen in middle age and doggedly wrote books (including in 1836 the first anti-slavery novel, Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw) to rescue the family from her husband’s debts? Trollope had witnessed his family’s financial decline because of his father’s imprudent investment decisions. He had suffered the ignominy of that at school, where his father’s ambitions meant that he was among wealthy young bullies while trudging twelve miles a day from a shack on the failed farm that Thomas Anthony Trollope had bought (after failing at the bar due to his incorrigible bad temper). Any romantic ideas that the young Trollope might have had about a helpful muse would have vanished along with his father’s expected inheritance that failed to materialise (after his elderly uncle married and produced an heir). Trollope obviously understood that only hard work was going to improve his circumstances, and he was not going to let his own family suffer as he had. A regular income from writing supplementing his income as a civil servant was what enabled him to provide for them according to their class and expectations. He was not going to idle about waiting for a muse to help him out!

He was also well aware that his continued success could not be relied upon, especially after he resigned from the Post Office early, thereby forgoing a pension. In his old age, reflecting on his present happiness, he says:

… who has had a happier life than mine? Looking round upon all those I know, I cannot put my hand upon one. But all is not over yet. And, mindful of that, remembering how great is the agony of adversity, how crushing the despondency of degradation, how susceptible I am myself to the misery coming from contempt, – remembering also how quickly good things may go and evil things come, – I am once again tempted to hope, almost to pray, that the end may be near. (p. 43)

Fortunately, by the middle of the twentieth century the academic carping from the critics of this autobiography was seen for what it was. (The public had never stopped liking his books, and the books were never out of print, even when most Victorian novels were out of favour). But quite apart from the pleasure of learning about a favourite author from his own hand, there are other reasons why this book is of value. Trollope’s descriptions of his writing process is fascinating.

In Chapter 5, ‘My First Success’, Trollope tells us about the creation of the mild-mannered elderly Septimus Harding in The Warden, who is confronted by a firebrand reformer called John Bold up in vociferous arms about the disbursement of charity funds between its administrator (the warden Septimus) and its intended beneficiaries in the town. (An issue still relevant today, eh?) The situation is complicated still further by John Bold’s romance with Septimus’s daughter Eleanor. Septimus, much loved in his community, is bewildered by John Bold’s lawsuit, and devastated by seeing his name and reputation scourged in the scurrilous newspaper Jupiter. His outraged son-in-law Dr Grantly harangues him to stand his ground and defend himself. You have to read the book yourself to see how Septimus, buffeted from all directions, resolves this situation.

It’s fascinating to learn that Trollope imagined all this so successfully without ever having had much to do with the clergy or ecclesiastical life. In a rare rejoinder to a contemporary critic, he also tackles the accusation that Tom Towers from the Jupiter is a thinly veiled reference to some editor or manager of The Times newspaper. Not so, he says, he had created the journalist Tom Towers just as he had created the archdeacon, (and all his other characters) entirely from his imagination

… and the one creation was no more personal or indicative of morbid tendencies than any other. If Tom Towers was at all like any gentleman then connected with The Times, my moral consciousness must again have been very powerful. (p.66)

Time and again he makes the point that an author should ‘live with’ his characters, know everything about them, and make sure that they change and develop over time just as people do in real life. He writes about these characters as if they were real people, mourning the ‘death’ of his Mrs Proudie as if she were a member of his family. He has much to say about the tension between reproducing ‘realistic’ dialogue with all its stops, starts and interruptions, and fluent, coherent speech which sounds forced and unrealistic in novels because people don’t talk like that in everyday life. I was also charmed by what he has to say to debut authors about the difficulties of writing that pesky second novel once the burning issue that motivated the first one has been dealt with. There’s also some cogent advice about the responsibilities of critics and how authors should deal with them ethically.

Of all the secrets of the publishing industry, the one that should be of most interest to us as readers is, what becomes of the failed first novel? Trollope tells us in Chapter 4 ‘Ireland – My First Two Novels’, about how his first efforts were unmitigated failures. Like all authors, he was pleased to see his name in print but [primed by his own self-doubt, as his contemporary readers can see] expected nothing to come of it. Further on, he reveals some of the maths: a publisher tells him about the cost of production and how much he has lost on it, (and how Trollope should give up writing). With the benefit of hindsight we might even feel sorry for this Mr Colburn in letting Trollope slip from his grasp, but the anecdote shows that publishers might well have printed 375 copies, sold only 140, and incurred a loss of £63, 10s. 1½d. Trollope isn’t very flattering about publishers yet somehow I have acquired the idea that publishing used to be a gentlemanly occupation, with publishers using their financial successes to nurture beginning authors and to absorb the losses of failed novels (and perennially poor-selling poetry books). Mr Colburn seems to have been one of these and he gave Trollope a start even if only 140 copies were sold. How many debut novels do today’s profit-driven publishers nurture, or are they leaving most of them to flounder through the self-publishing swamp? Do they dump the authors of the failures, as Mr Colburn may have come to rue? And have the profit/merger-driven staff purges left the major publishers with insufficient expertise to spot the talent, as Mr Colburn failed to do?

Trollope did not give up. He so badly wanted to be a writer, and [primed to follow Frances Trollope’s inspiring example, as the reader sees from Chapter 2, ‘My Mother’] he saw so clearly that an income derived from writing could not only give him financial security but also restore his position to the status of gentleman which was his by birthright.

The rest, as they say is history, and the autobiography traces his progress through the publishing history of his career.

For readers seeking to know more about the man himself (and his wife about whom he says barely a word), I’ll let him answer that directly:

It will not, I trust, be supposed by any reader that I have intended in this so-called autobiography to give a record of my inner life. No man ever did so truly, – and no man ever will. Rousseau probably attempted it, but who doubts but that Rousseau confessed in much the thoughts and convictions rather than the facts of his life? If the rustle of a woman’s petticoat has ever stirred my blood; if a cup of wine has been a joy to me; if I have thought tobacco at midnight in pleasant company to be one of the elements of an earthly paradise; if now and again I have somewhat recklessly fluttered a £5 note over a card-table; – of what matter is that to any reader? (p.226)

BTW For lucky readers who live in London, there is a Trollope Society where you can have jolly dinners together and take guided walks with other enthusiasts.

PS The ‘Other Writings’ are:

- Trollope on Jane Austen

- ‘On English prose Fiction as a Rational Amusement’ (which amplifies what’s in my Sensational Snippet)

- From Thackeray

- From ‘The Genius of Nathaniel Hawthorne’

- From ‘A Walk in the Wood’

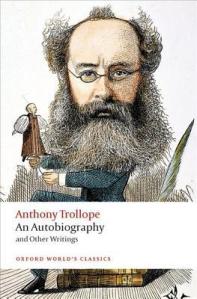

Author: Anthony Trollope

Title: An Autobiography and Other Writings

Publisher: Oxford Worlds Classics, 2016, first published 1883

ISBN: 9780199675296

Source: Review copy courtesy of Oxford University Press

Available from Fishpond: An Autobiography: And Other Writings (Oxford World’s Classics)

I posted on this a while back (and even closed with a snippet of the same quotation you used!), but my older edition had no ‘other writings’ – what are they?

P.S. I also have Victoria Glendinning’s biography to get to at some point, which will offer an alternative view to Trollope’s…

LikeLike

By: Tony on February 4, 2017

at 6:36 pm

HI, Tony, good to hear from you…

I’ve listed the titles of the other writings at the bottom of the post. They vary in length from just a couple of pages (‘on Austen’) to 24 pages (‘English prose’).

I can’t find your review to see which one you used, but it’s not the first time I’ve chosen the same excerpt as someone else!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 4, 2017

at 7:14 pm

Sounds fascinating – and I fortunately have a copy of this! (Yay!)

LikeLike

By: kaggsysbookishramblings on February 4, 2017

at 7:32 pm

I hope you love it too:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on February 4, 2017

at 9:39 pm

Thanks for that :) Here’s the link to my review:

And here’s the link to all my Trollope reviews (this one and twenty others at present!):

https://tonysreadinglist.wordpress.com/category/anthony-trollope/

LikeLike

By: Tony on February 4, 2017

at 7:33 pm

Strange how it didn’t come up in my search…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 4, 2017

at 9:39 pm

Unfortunately, in the second and third years of my blog I chose witty titles for the posts which didn’t feature the titles of the books, meaning that nobody will ever find them…

LikeLike

By: Tony on February 5, 2017

at 12:03 am

It’s a bit of work, but you can do something about that now that you’ve moved them over to WordPress.

From WP admin, click on all posts and work your way to the offending titles. Click on Quick Edit, and in the box for tags, write the title and the author’s name, separated by a comma.

You can also edit title itself but you must remember to alter the slug as well, a bit, or completely i.e. you could add the title & author’s name in brackets after your original witty title, or you could just delete the original title altogether and replace it.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 5, 2017

at 8:40 am

I’ve thought about it, but I doubt I’ll be doing it any time soon – it takes all my energy just to keep up with my present blogging :)

LikeLike

By: Tony on February 5, 2017

at 10:25 am

I read my first Trollope, The Warden, last year. I hope to read some more by him but I can’t see him becoming a favourite of mine.

LikeLike

By: Jonathan on February 4, 2017

at 10:23 pm

Did you review it on your blog? I’d like to link to it if you did:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on February 4, 2017

at 10:31 pm

I don’t think I did. I end uo blogging on so few books I actually read as it cuts in to reading time. My edition, from the library, had a couple of stories which I liked more than the main piece. Still, if Trollope’s other novels are as good as ‘The Warden’ then I’ll read more.

LikeLike

By: Jonathan on February 4, 2017

at 10:41 pm

Well, *chuckle* you’ve plenty to choose from because he wrote 47 of them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on February 4, 2017

at 10:58 pm

‘Barchester Towers’ is a far better (and more enjoyable) book than ‘The Warden’, and you’ll like it the better for knowing many of the characters from the first book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Tony on February 5, 2017

at 10:26 am

True, but you won’t recognise the characters from the first book if you don’t read it first! I like the way The Warden sets the scene for what follows, but I suppose, given the pressure we all feel to read so many books, not everyone is going to read them all.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 5, 2017

at 12:45 pm

Thank you for reminding me how much I enjoyed the Autobiography, as well as just about everything else the man wrote. As to the “critics”, would they have preferred the man to be indolent!

I discovered Trollope when they ran The Pallisers on public tv. I went to the books and have never stopped. The tv version of The Way We Live Now, with David Suchet as Melmotte, is particularly good. I hope you have seen it in Australia.

LikeLike

By: SilverSeason on February 4, 2017

at 11:42 pm

Oh, Susan Hampshire, what inspired casting that was! Philip Latham too:) I bought the series on DVD just recently and binge watched it while scrapbooking my last holiday, no wonder I’m still not finished the scrapbooking…

I liked The Way We Lived Now too, again inspired casting with David Suchet looking suitably disreputable, but my favourite will always be The Barchester Chronicles with David Pleasance as the warden.

IMO these Trollope adaptations are the very best that the BBC has ever done.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 5, 2017

at 8:47 am

I’ve always wanted to read Trollope but never know where to start. Is there a particular title you’d recommend?

LikeLike

By: kimbofo on February 5, 2017

at 12:51 am

Hi Kim, I think I’d read The Warden. It will change the way you wander among those old English churchyards forever, because it will bring them alive…

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on February 5, 2017

at 8:49 am

The sheer number of his novels probably contributed to the under appreciation. It’s the same thing with Simenon.

Please tell me you’ve seen The Way We Live Now (?)

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on February 5, 2017

at 9:30 am

Oh, yes indeed, see my reply to Nancy!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 5, 2017

at 9:36 am

Ok now I see it. I don’t usually read through the comments. I was disappointed in the recent Doctor Thorne,

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on February 5, 2017

at 9:56 am

I enjoyed it, but it wasn’t as compelling as the others because it was too easy to see how it was all going to end up.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 5, 2017

at 12:43 pm

Some of the casting seemed wrong IMO and yes it was all a bit too simple.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on February 5, 2017

at 5:00 pm

[…] Anthony Trollope’s Autobiography and Other Writings which I reviewed here. I was very fond of that book, but good manners prevents me from telling the story of how I came to […]

LikeLike

By: The Last 10 Books Tag | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 25, 2018

at 9:01 am