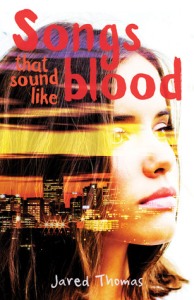

Every now and again, along comes a book that really deserves a wider audience than it might be getting. Songs That Sound Like Blood by Nukunu man Dr Jared Thomas is just such a book, marketed for YA but well worth reading by readers of any age.

Every now and again, along comes a book that really deserves a wider audience than it might be getting. Songs That Sound Like Blood by Nukunu man Dr Jared Thomas is just such a book, marketed for YA but well worth reading by readers of any age.

This week we have seen our politicians in an unedifying stoush over the Fair Work’s Commission decision to cut penalty rates for weekend workers in hospitality and retail. We have also seen a chorus of small business owners telling the media that they might put on extra staff as a results of this decision. Unlike the uncritical journos interviewing them, these business owners can do the maths: cutting a workers pay by between $4000 and $6000 a year doesn’t give an employer enough to create a real new job. They will pocket the difference, thank you very much, and you and I won’t get served any quicker by the worker taking home his/her much reduced pay.

No, this decision is a squeeze on the wages of young people to improve profitability – because young people are the ones who staff our cafés, and who do the weekend shift at pharmacies and the like. As one who has been self-supporting since the age of seventeen, I reject the assumption that young people don’t need real jobs that pay enough for independent living. But it is this generation of 18-24 year-olds that is bearing the brunt of our increasingly mean economy, and they are finding life difficult. Housing and rental affordability is an issue; job security no longer exists; unemployment benefits are #understatement inadequate but governments aren’t doing much to create jobs (especially in rural areas); and cuts to TAFE and universities just go on and on, making it even more difficult for young people to earn qualifications to better themselves.

Was it just a day or two ago that I expressed a yearning for books that tackle the issues of our time? Songs That Sound Like Blood is the story of Roxy from Port Augusta in South Australia, who is at the sharp end of this contraction in opportunities for young people. The blurb tells only half the story:

Roxy May Redding’s got music in her soul and songs in her blood. She lives in a small, hot, dusty town and she’s dreaming big. When she gets the chance to study music in the big city, she takes it. In Roxy’s new life, her friends and her music collide in ways she could never have imagined. Being a poor student sucks… singing for her dinner is soul destroying… but nothing prepares Roxy for her biggest challenge. Her crush on Ana, the local music journo, forces Roxy to steer through emotions alien to this small-town girl. Family and friends watch closely as Roxy takes a confronting journey to find out who she is.

The book is marketed as an insight into LGBTI young people coming to terms with same-sex relationships, and it is terrific from that angle. Written from Roxy’s first-person perspective, the reader sees her doubts and uncertainties about the relationship itself, and about how to break the news to her family and community. Ana’s parents Jordan and Naomi, and her sister Em are fine with Ana’s sexuality but Roxy is right to be not so sure about the reception she’ll get. She gets counselling about how to handle it, but it doesn’t stop her forthright Aunty Linny from getting a tongue-lashing from Nanna:

Nanna looked at me like she was going to blow a fuse. ‘ Now listen here, Linny. You know the thing I hate more than anything? It’s people with no business being judge-bloody-mental. And you know how people are in this town. They’re all ra-ra-ra and who are they to judge? Her voice was almost breaking she was so angry. ‘And you know where that judgement got our people? It got your old people in missions, your great-grandmother charged with murder when her first child died in childbirth, and thank god someone had better judgement or we wouldn’t be here.’ Nanna calmed down a bit and then asked, ‘Who are we to judge, Linny?’ Nanna started crying and then she said, ‘She’s my Roxy and I love her just the same.’ (p.222)

I loved the moment when Aunty Linny demands to know how Roxy can have children, and Dad’s new girlfriend Angie retorts with ‘Oh, that is so bloody backward’ !

I also liked the way the book inverts the usual success story. Roxy finds the future she wants but her BFF Helen doesn’t because she doesn’t take the initiative like the indigenous young woman does. Helen loses her virginity in a disappointing way – too drunk to remember whether she used protection or not, with a bloke who barely acknowledges her the next day – whereas for Roxy it’s a magical moment in her life.

But there is more to this novel than coming out as gay. Roxy is a young Nunga woman, and her pathway out of limited horizons begins with a trip to the big city of Adelaide. Helen has done well at school too, but she’s expecting just to get a job in admin or retail because her parents don’t want her to leave town. But Roxy has seen a glimpse of something more than that:

I’m not sure if Helen knew that I went to the city at the beginning of the year to look at course and career options with other Nunga kids. I probably pretended I was sick or something so she wouldn’t know where I was. She’s my best friend but I’m so used to hearing what white people think that sometimes I don’t tell her things.

Kids at school talk about us Nunga kids getting special treatment because once in a while we get to do something with our own people. I mean they got to learn about their culture in class, from their own people, in their own language. (p.16)

With their teacher and their Aboriginal Education workers, Roxy and the other Nunga kids travel three hours to what seems like a world away to hear Aboriginal bands making music:

I had to hold back really hard from crying. I was just so happy to know that something like that existed. That night, in my sleeping bag at the caravan park, I felt so proud of those musicians and imagined I was one of them.

The next morning we checked out the university and this place there called the Department of Aboriginal Music. Oh man it was deadly. Some of the musicians we watched the night before, that’s where they went. I saw some of them in their classes.

That trip was the best thing that had ever happened to me in my life. The uni was as big as a city, and that’s where I decided I wanted to go. I just had no idea how to make it happen. I mean I knew I had to get good exam results, write an application and then do an audition but even if I was accepted, how would I get there? (p.17)

Well, it’s not a spoiler to share that Roxy gets help to find accommodation from Jill and Charlton, the support workers at the university, but she uses her own initiative to take the plunge into the city music scene because she needs the money to be able to cover transport, food and rent. It was fascinating to see how she adapted her material to suit different audiences – playing originals, some of [her] favourites, and then a few edgy alternative and country numbers – and how she learns not just the ropes for cutting a demo USB, but also how to do research and structure an essay so that she starts to see the possibility of further study.

The book is full of references to Roxy’s eclectic choice of music. Some, like ‘My Island Home’ by Neil Murray and performed by the Warumpi Band are very familiar, but as I found when I went exploring with You Tube, the book is also an education in the rich field of indigenous music.

This is the haunting music of Frank Yamma:

And this is surely a great clip of the group ‘Wildflower’, from the remote Arnhem Land Outstation of Mamadawerre, to represent what Roxy stands for:

(And when you watch Wildflower in action, be aware that these young people can’t see it like you can because (as I discovered from this interview) in their remote home, they don’t have internet or even a shop that sells magazines that feature their story.)

It was a revelation to me some years ago to learn that exports of contemporary Australian music was a huge money-spinner for Australia so there’s good reason for taxpayers to support young musicians. There’s a huge international market for Aboriginal art, so why not in Aboriginal music too?

It’s only going to happen if there’s effective support. Songs That Sound Like Blood moves into political territory when Roxy – who’s had enough support to transition into mainstream music courses – realises that some of her fellow students aren’t ready for that yet. Their opportunities will be compromised if budget cuts at the university reduce their access to courses and to education support services. Of course music is a big part of their protest!

The book is also reviewed at Kill Your Darlings, in the context of books being pitched at a slightly older age group than traditional YA, and there’s also a review at the NSW Writers’ Centre. But it should be getting more attention that that, so get a copy and spread the word!

Dr Jared Thomas is a Nukunu man from the Southern Flinders Ranges.

Author: Jared Thomas

Title: Songs That Sound Like Blood

Publisher: Magabala Books, 2016

ISBN: 9781922142658

Review copy courtesy of Magabala Books

Available from Fishpond: Songs That Sound Like Blood

Or direct from Magabala Books

Will pass the good news to younger members of family and read it myself.

LikeLike

By: Fay Kennedy on March 5, 2017

at 10:36 pm

I love it when readers tell me that after they’ve read one of my reviews, it makes it all worthwhile!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on March 5, 2017

at 11:11 pm

Well done on this post on ALL fronts. Polls are so out of touch that one can walk in constant anger if not careful. An important book for young people and you’re spot on regarding indigenous music.

LikeLike

By: travellinpenguin on March 6, 2017

at 9:10 am

Well, I did enjoy writing it:) You know how YouTube just moves onto the next thing it thinks you’re interested in… I just left it playing while I wrote and it moved from one great indigenous band to another.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on March 6, 2017

at 10:10 am

I’m with you on indigenous music but are you happy with a guy writing a first-person lesbian novel? And in passing, I think Helen’s experience of first sex is far more common than Roxy’s.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on March 6, 2017

at 11:12 am

Yeah, I meant to mention that but I got interrupted in the middle of writing this, switched computers and forgot!

It’s an interesting choice, and I think it works quite well, because the voice sounds authentic, both in terms of Aboriginality, gender and age-group. I’m still ambivalent on this question of identity politics and writing, but taking this book on its merits, I think it works.

It would be interesting to ask the author about this…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on March 6, 2017

at 11:51 am

I’m sure the author has lots that is new (to us) to say about being Aborignal, and young, in SA. I was going to say when is IWW but I looked it up – first full week in July. I’ll have to think of something to read.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on March 6, 2017

at 12:11 pm

Me too! I was saving this one for ILW but couldn’t restrain myself. I’ve got 13 in my TBR stash but nothing new at all, and yet I’m sure there must be some new novels out there by Indigenous authors…

This is one place to look but there doesn’t seem to ne anything new since last year http://www.uqp.uq.edu.au/CategoryBookList.aspx/62/Black%20Australian%20Writing

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on March 6, 2017

at 12:23 pm

[…] think, but then a few posts later, when reviewing Jared Thomas’ Songs that sound like blood, she made clear that she meant by this “a yearning for books that tackle the issues of our time”. Ah, I […]

LikeLike

By: Monday musings on Australian literature: Books that matter | Whispering Gums on March 13, 2017

at 11:46 pm

I started thinking about writing a narrative from the perspective of a young Aboriginal lesbian early in 2013 and then shortly after the release of ‘Calypso Summer’ I was asked by Magabala Books to write another novel. In order to accelerate the writing process I decided to write about music, the music industry and changes occurring within the tertiary education sector – all worlds I know well. They’re also worlds that my eldest daughter is negotiating as an emerging singer songwriter.

I knew the book could have worked featuring a hetrosexual relationship, in fact it probably would have increased the chances of its commercial success but I thought it important to make Roxy lesbian.

The main impetus for writing Roxy as a lesbian is because suicide levels among Aboriginal youth are amongst the highest in the world and elevated among same sex attracted Aboriginal youth. I wanted to write a book that young same sex attracted Aboriginal people could see themselves within.

Before setting off writing in this direction, I talked with lesbian friends in Australia and New Zealand about my aspiration, asking if they’d be happy to respond to questions and provide feedback on drafts. I also requested that the publisher, Magabala Books, employ an anonymous lesbian reader to provide feedback and that if at any point the representation was lacking integrity, they tell me so that I could contemplate changing direction or scrapping it altogether.

My goal in writing about Roxy and Ana was to represent loving and supportive relationships similar to those of my gay and lesbian friends and family members. At first I didn’t want ‘Songs that Sound like Blood’ to be a coming out story but one of the key comments from the reader’s report was that it wouldn’t be plausible for Roxy’s friends and family not to pass comment on Roxy’s first lesbian relationship.

I’m always very interested in feedback from lesbian and gay readers.

LikeLike

By: Jared Thomas on March 19, 2017

at 8:45 pm

Thanks you Jared for this wonderful response to my query: I’m very grateful. I’m pleased to hear that the book has the approval of those it represents: I thought the characterisation was authentic, but I was only basing that on what I knew of my gay and lesbian friends.

I was pleased to see that #LoveYAOz had read my review and retweeted it, so I hope it gets plenty of publicity and makes its way into the world of young people that you are trying to reach.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on March 19, 2017

at 10:25 pm

[…] Songs That Sound Like Blood (2016) by Jared Thomas […]

LikeLike

By: 2017 ANZLitLovers Australian and New Zealand Best Books of the Year | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 30, 2017

at 4:26 pm

[…] have changed but it’s still not easy as you can see in Jared Thomas’s Songs That Sound Like Blood (2016). It offers an insight into LGBTI Indigenous young people coming to terms with same-sex […]

LikeLike

By: Six Degrees of Separation, from Tales of the City, to… | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on July 7, 2018

at 1:14 pm