Indigenous Australians are respectfully advised that the following post includes the names of deceased persons.

Indigenous Australians are respectfully advised that the following post includes the names of deceased persons.

***

At the end of tonight’s TV news, I caught a snippet about an exhibition of indigenous artworks that’s on show at the Mornington Regional Gallery until October 2nd. It’s called Desert Country, and it features work on loan from the Art Gallery of South Australia, from indigenous artists of the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia. These artists include Albert Namatjira, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Daisy Leura Nakamarra, Rover Thomas, and Utopia artists Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Kathleen Petyarre. These are pre-eminent Australian artists and internationally famous, and it’s an opportunity to see and learn about their work that I don’t intend to miss.

The article reminded me that Wakefield Press had sent me a copy of Yulyurlu Lorna Fencer Naparrurla. This is a beautiful book about the quixotic artist known as Yulyurlu, who was a pioneer of the Central Desert Art movement. I am the first to admit that I know very little about Aboriginal art so I found her story fascinating.

Like many desert people in mining regions, she had a disrupted life, and more than her fair share of tragedy. She lost eight of her ten children, seven of them predeceasing her in childhood, and one – Elizabeth Martin Napangardi born at Mt Doreen c1952-3 – was taken from her by Native Welfare and never seen again. Despite being shunted around by circumstance, Yulyurlu retained a passionate attachment to her culture and was extremely knowledgeable about her people’s Dreamings. Once introduced to acrylics in the Lajamanu School art program in 1986, she began painting prolifically and became highly sought-after. Although she was at times subjected to exploitation (see Wikipedia for more about this) she remained fiercely independent and utterly devoted to her art, sometimes to the extent that she isolated herself from others.

As I understand it from the chapter by Christine Nicholls, Yulyurlu inherited from her father ‘the right to dance, sing and illustrate the Marlujarra Jukurrpa (Two Kangaroos Dreaming)‘ (p44) as well as the Yam Dreaming Complex (Big Yam, Little Yam and Caterpillar). These were crucial aspects of her identity and she retold the stories from these Dreamings again and again, in different ways as she experimented with different styles. She painted big, broad and often vibrantly colourful images, with bold brushstrokes depicting the central roundel of the yam or its root structure. For her Kangaroo Tucker paintings she used a decisive floral motif, and strong linear elements for the Snake, Lover Boy Dreaming. At other times she used dot matrices to illustrate the caterpillar dreaming, so she was very versatile. This versatility extends to her use of colours, which range from subdued ochres and browns, to vibrant primary colours and soft pastels. I wish I could show you some of these gorgeous pictures, but that would breach copyright, so you will just have to get hold of a copy of the book to see them. (Unlike most art books, it’s not very expensive, only $34.95 even though it features extensive full colour plates. )

I can only guess at the importance of these Dreamings from the controversy which surrounded early artworks about them. Some Warlpuri community members expressed concern that depicting such designs in a permanent way rather than just in the mind, was a violation of traditional law. One leader, Maurice Jupurrurla, argued that the Papunya Mob had ‘quite literally ‘sold out’ their religious beliefs by selling their artworks to unknown mostly ignorant people in the dominant culture.’ (p49) and until his death in 1985 public opinion was against the creation and sale of artworks using acrylics.

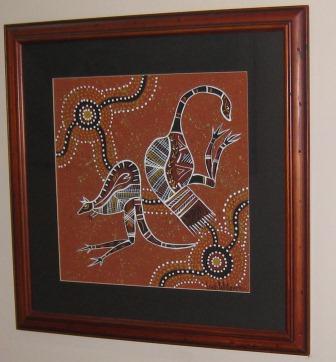

Things have certainly moved on since then and today Aboriginal art is exhibited to international acclaim and there is a thriving market for this unique art movement. I myself have a lovely painting by Linda Williams from the Brabralung People of the Kurnai Tribe in East Gippsland: my younger sister gave it to me as a gift. I don’t know its story except that it came from an Aboriginal Cooperative on the outskirts of Geelong. (To see other paintings by this artist, click here).

Things have certainly moved on since then and today Aboriginal art is exhibited to international acclaim and there is a thriving market for this unique art movement. I myself have a lovely painting by Linda Williams from the Brabralung People of the Kurnai Tribe in East Gippsland: my younger sister gave it to me as a gift. I don’t know its story except that it came from an Aboriginal Cooperative on the outskirts of Geelong. (To see other paintings by this artist, click here).

One of the things I really like about this book is that every painting is properly named, described, dated and its location acknowledged. The contributors have each shared their memories of the artist in a deeply personal, affectionate way without tempering their honesty about her sometimes difficult temperament. It’s a beautifully presented book and would make a really nice gift for anyone interested in art.

Update: September 20th 2011

I have just read a rather chastening article entitled ‘Colours fade to black’ in The Australian Literary Review by Dr Philip Jones (7 Sept 2011). (Dr Jones is the author of Ochre and Rust which I read a little while ago). (That’s the ALR in The Australian newspaper, not the journal, and it’s not available online except to subscribers).

I hope I am not misrepresenting what Dr Jones says when I summarise his concern that we may have seen the last of the great Central Australian painters. He makes the point that spiritual beliefs were central to the artists whose magnificent work of the last 30 years has served to foster understanding of Aboriginal Creation ‘logic’ into European understanding of the desert, in the sense that ‘the notion of an animated Aboriginal landscape increasingly colours our impressions of this country’s deserts, mountains, rivers and lakes.’ It was the popularity and commercial success of Central Australian artists working in new media that brought awareness of these spiritual dimensions to a wider audience. But the artistic and intellectual significance of these art works is contingent on their makers having a deep spiritual connection to the land and a detailed knowledge of its mythology and landscape. And while he recognises that these beliefs are sturdy:

For most Aboriginal artists the clear ancestral imprint is simply too evident in the landscape, obligatory and unavoidable. That is unlikely to change, even as the last generation of grand old artists, born before Europeans fenced and stocked their land, fades away.

he fears that

now as ceremony winds down in the centre and the old stalwart artists fade like Gallipoli veterans, the landscape itself and the literature defining its poetic link with the Aboriginal society take on a crucial importance.

Food for thought…

© Lisa Hill

Editor: Margie West

Title: Yulyurlu Lorna Fencer Naparrurla

Publisher: Wakefield Press, 2011

ISBN: 9781743050095 126pp, col.ill.

Source: Review copy courtesy of Wakefield Press

Availability: Click the link above to buy from Wakefield Press online.

Sounds like a gorgeous book Lisa. We have a very small collection of indigenous art bought in Central Australia, Tiwi Islands and the Pilbara – I love looking at it. One of my very first little contracts after I retired was researching Emily Kame Kngwarreye ‘s life for a video to go with an exhibition of her paintings that was going to only two places I think: Tokyo and the NMA here. Late last year/early this year there was a well-attended exhibition of art from the Canning Stock Route area, also at the NMA. Some of these artists had an exhibition in San Francisco in the middle of this year. It’s wonderful seeing this work coming more and more into the public sphere – here and overseas.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on September 16, 2011

at 9:29 am

Any chance you might be writing a bio of Emily Kame Kngwarreye , to lift her local profile, Sue? It really annoys me that so many Australians have never heard of her and yet the price that’s paid for her work on the international market shows that she’s a major artist. I feature her in a presentation that I have gaven a number of times about Aboriginal Perspectives in Education. (The slide show is at http://wp.me/PdjEw-8) First I show The Pioneers by You-Know-Who and then I show one of Jimmy Possum’s works and ask if anyone knows who it’s by. No one ever does. And then I show them this site: http://moderato.wordpress.com/2007/06/17/australias-most-valuable-aboriginal-painting-on-view/ – and point out to them that Emily’s work sold for over AUD$1 million. I really think we should be more upfront about celebrating these successes from the oldest living culture in the world…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 16, 2011

at 2:03 pm

Oh no, Lisa, I don’t think I’ve got the staying power to write a book like that. I’m far too dilettantish to settle to such a long project (much as I’d like to think I could!) I’ll check those links though … we certainly should be more upfront. It’s embarrassing that indigenous art is almost (if not really) more appreciated overseas.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on September 20, 2011

at 9:15 am

I know that Sue McCulloch has written a reference book about Aboriginal art, maybe she might do it one day…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on September 20, 2011

at 6:14 pm

[…] may remember that when I posted a review of the biography of the Central Desert artist Yulyurlu Lorna Fencer Naparrurla, and more recently about Aboriginal art in Victoria in Meerreeng-an – Here is My Country, I […]

LikeLike

By: McCulloch’s Contemporary Aboriginal Art The Complete Guide | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 22, 2018

at 6:05 pm