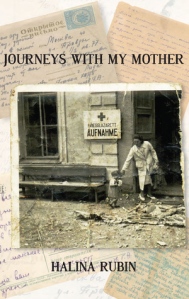

Journeys with My Mother is an extraordinary story: despite the author’s skill in telling it, I still can’t quite imagine how an indomitable woman twice managed to escape the Germans, each time with a small child in tow. It seems unbelievable and yet it is true.

Journeys with My Mother is an extraordinary story: despite the author’s skill in telling it, I still can’t quite imagine how an indomitable woman twice managed to escape the Germans, each time with a small child in tow. It seems unbelievable and yet it is true.

Halina Rubin was born to secular Jews in Warsaw in 1939 at the time when Hitler and Stalin had signed a non-aggression pact and Hitler was free to attack the city. As people who believed that communism was a viable alternative to the poverty around them, Ola and Wladek saw the Soviet Union as a refuge, and fled to Bialystok, just across the border, a once Polish town in Soviet hands thanks to the trade-off with Hitler. (The book has a helpful map at the front, that shows where these places are).

If you have seen Roman Polanski’s film, The Pianist, you have some idea of the devastation wrought upon Warsaw and the horrors of the ghetto, but for Ola the disaster began just a few days after she gave birth.

Her room was full of roses. Afterwards, she could not recall who else had visited her and who’d delivered the flowers. We were still in that hospital room when the war began four days later, when the real bombs started falling on Warsaw, when people were killed, buildings ablaze from incendiary bombs.

A few days later our hospital, too, was on fire. As the flames and smoke spread, screaming terrified women ran out of the wards. Some, in haste, left their babies behind and were now howling for help to retrieve them. (p. 104)

Ola fled into the street:

… Ola, torch in hand, holding me tightly, grasped her little case already packed for such an emergency and went out into the street unaided. The descending darkness was illuminated only by searchlights, fires and her torch. Someone directed her to the nearest shelter.

But the shelters were unbearable. This woman, with a baby only days old, door-knocked until she found a young couple willing to take her in. Miraculously, she was briefly reunited with Wladek, but as the author calmly puts it A peaceful night with both adoring parents beatifically leaning over my cradle was not my fate.

Hopes that the allies would save Poland from its fate were premature: although war was declared neither Britain nor France were militarily ready and the reality of the Phony War led Poland to capitulate:

Towards the end of the month, Hitler, watching fires consuming the city, demanded capitulation. It was rejected and punishment was meted out on the day remembered as Black Monday. Those who lived through it thought it signalled the end of the world, or what hell must be like. Nothing was spared from the relentless assault which lasted all day. Entire streets were on fire – houses, churches, hospitals, schools and markets turned to ruins. That day, ten thousand civilians were killed. From then on, there was no water and no electricity, no gas.

Starzynski [the mayor of Warsaw who took charge during the siege of the city] spoke to the allies: ‘You are sending us from Paris, from London congratulations and best wishes. We don’t want any. We no longer expect your help. It is too late for that … We seek vengeance. (p. 111)

But as we all now know, Hitler broke his pact with Stalin, and unleashed the full fury of the Soviets. Even less prepared for war than Britain, the USSR used all its resources to re-arm and to mount a counter-attack. Ola and Halina were separated from Wladek and were sent with prisoners-of-war further east to the town of Lida. But this was disastrous too, because under the German Occupation in 1941, the ghetto was liquidated and the community murdered in 1943. Ola and four-year-old Halina survived with other partisans in the surrounding forest until the city was liberated in 1944.

At the very beginning of the war when the Wehrmacht rolled across the land, laying waste to the countryside and its people, scattering those still alive in all directions, hundreds of terrified human beings – local men and boys, odd deserters, inadvertently abandoned army soldiers, Russians, Poles, Jews, Gypsies and Belorussians – sought the protection of the forests. As for the Jews, there were no concentration camps in Belorussia; death came to them where they lived. Those who understood the inevitability of annihilation summoned the courage to leave their hiding places, the ghettoes, to join the fighters. They fled despite the possibility of being robbed, even murdered by the very partisans they intended to join. For all the horrendous losses, the number of partisan fighters kept increasing. (p. 195)

Women, of course, were not generally welcome. But these POW escapees and their carers from the hospital in Lida offered the partisans something of value:

It was well known that partisans were loath to take in people who did not have firearms, especially women. But in our party, all twelve women were nurses and every man was skilled at using weapons. We carried with us precious essentials: medical instruments, dressings, medications, linen, plus an impressive array of weapons, ammunition, even two generators. (p.193)

Still, it beggars belief that a four-year-old child lived among them! Yet it is documented in papers held by a man called Vasilievich in Lida, and it is his turn to be amazed when he realises who he is meeting when Halina arrives to further her research and he shares the testimonies of a handful of partisans and NKVD documents:

One of the statements records the presence of ‘a four-year-old girl’ who was brought to the forest on the night of our escape. Whoever wrote it had no knowledge of to whom, if anyone, I was attached.

I tell Valeri that the woman sitting in front of him is that four-year-old child. Now he wants to hear my mother’s life from me. Yes, this is the long version. I take a deep breath and begin.

It is his turn to be astounded: how could a Jewish woman with a child, a refugee from Warsaw, have survived those violent years? From his perspective, Warsaw is as far away as a different continent. An extraordinary woman, he repeats, and I am flushed with pride and pleasure. (pp. 186-7)

I have read quite a few war stories and stories from the Holocaust, but most of them have been by and about men. This story remained buried in boxes of letters, papers, photographs and notebooks for many years after Ola Rubin’s death, until Halina Rubin decided finally to explore them and uncovered her mother’s heroic history through painstaking reconstruction and arduous journeys to Poland and Belarus (Belarussia during the war, and originally part of Poland). Halina’s journey also involved a process of self-discovery as she began to realise that her own behaviour as an adolescent contributed to the impossibility of finding some answers. She did not always listen, she did not always ask the right questions, she did not always respect her mother’s courage and tenacity. When by a stroke of luck Halina met Vasilievich who confirmed her mother’s role as a nurse with the partisans, she was overwhelmed – it’s as if, until that moment, some part of her was resistant to her mother’s remarkable story – because it is such an incredible achievement.

I wonder if the children of Syria, will in years to come, find scraps of their parents’ lives in boxes and try to resurrect their stories of flight from ISIS…

Author: Halina Rubin

Title: Journeys with My Mother

Publisher: Hybrid, 2015

ISBN: 9781925272093

Review copy courtesy of Hybrid

Availability

Please note that in the interests of social cohesion,

comments on all books about the Holocaust or set in Palestine or Israel,

and books written by Palestinian, Israeli, and Jewish authors are closed for the duration.

I have taken this action because of intemperate comments made by readers

who have ignored requests to refrain from commenting on the current conflict.

Terrific, thanks Lisa.

PS Check out our new website.

Regards Anna Anna Rosner Blay Managing Editor HYBRID PUBLISHERS PO Box 52 Ormond VIC 3204 Tel: (03) 9504 3462 Fax: (03) 9504 3463 See our website at: http://www.hybridpublishers.com.au

>

LikeLike

By: ablay1 on October 21, 2015

at 2:03 pm

You’re welcome, Anna:) The website looks very classy now!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 21, 2015

at 4:44 pm

What an amazing story Lisa – I wonder indeed about all the refugees in the current world – a book like this may give some hope that it is possible to survive and rebuild your life. Great review.

LikeLike

By: mairineilcreative writer on October 21, 2015

at 2:53 pm

Thanks, Mairi, it’s just one of many stories that could be told in our city, I suspect:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 21, 2015

at 4:42 pm

[…] Lisa (ANZLitLovers) also enjoyed the book. […]

LikeLike

By: Halina Rubin, Journeys with my mother (Review) | Whispering Gums on January 27, 2016

at 11:32 pm