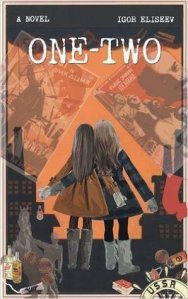

There is a terrible moment in Igor Eliseev’s new novel One-Two when the reader realises the reason for its strange title: Faith and Hope are conjoined twins who have been abandoned by their birth mother, experimented on at the Institute of Paediatrics and then the Institute of Traumatology, and finally dumped in a foster home where every child is given a degrading, insulting nickname. The story is narrated by Faith, with only occasional interjections from Hope, but it is she who speaks up when confronted by the indifferent cruelty of their new ‘home’ where they are told they belong in a zoo:

There is a terrible moment in Igor Eliseev’s new novel One-Two when the reader realises the reason for its strange title: Faith and Hope are conjoined twins who have been abandoned by their birth mother, experimented on at the Institute of Paediatrics and then the Institute of Traumatology, and finally dumped in a foster home where every child is given a degrading, insulting nickname. The story is narrated by Faith, with only occasional interjections from Hope, but it is she who speaks up when confronted by the indifferent cruelty of their new ‘home’ where they are told they belong in a zoo:

‘Good afternoon, Inga Petrovna. My name is Hope, and she is Faith.’

The principal gave us a sharp look that immediately accused us of all our past wrongdoings and of our future ones, too, including, first and foremost, the fact that we had had the audacity to be born, and chillily summarised:

‘That’s too long to keep in mind. You will be One, and you,’ she pointed at me ‘you will be Two.’ (p.27)

It’s heart-breaking to think of children being denied even their own names…

The resilience of these two girls who suffer appalling insults, neglect and exploitation in the Perestroika period in Russia is emblematic of the resilience of the Russian people and the suffering they have experienced during the 20th century. In a chapter entitled ‘Injustice as a Standard of Living’, the girls have this conversation:

Suddenly an incredible thought came into my mind.

‘Hope,’ I started, ‘what if initially they had named you Faith and me Hope, but afterwards they forgot which was which and swapped our names around by mistake? You always believe that everything is going to be all right, and your faith helps me.’

‘And you hope that it will be that way. We have this close bond between us.’ After thinking a while, you added, ‘All people need hope, no one can live without it; and our hope is way stronger when it is warmed up by faith. So it isn’t really important who is Faith and who is Hope; the main thing is that we are connected together. (p.57)

The irony is that while these girls are inseparable because of their congenital deformity, the USSR is rapidly disconnecting itself, as one republic after another declares independence.

The story traces the girls’ eventual escape from the foster home, but things are no better in the capital (which I assume is Moscow). Although they are highly intelligent and hardworking, there is no work for them and they become homeless, reduced to begging in one of the underground tunnels of the Moscow Metro – and handing over much of their ‘earnings’ to a pimp.

Their commentary in the chapter called ‘Tomorrow was the Country’ on the massive changes taking place in Russia is familiar to those of us who remember the stories of terrible hardships as the Soviet Union dissolved and a market economy was suddenly imposed.

By a twist of fate, we turned out to be a special environment, the special environment where things can be seen most clearly. The tunnel was our auditorium, with daily classes in psychology and philosophy. We secretly watched generations in pursuit of a better life: tearing former pictures, throwing out old books, changing erstwhile slogans – swearing off anything valuable in the country’s history. Thoughts of survival became rooted in people’s minds so deeply and tenaciously that all principles of conscience were discarded as useless, and only “saving” alcohol could quench the thirst for oblivion and idleness. Those ties we didn’t drink very often and exchanged vodka, which had became [sic] a principal means of payment, for food or services. The prices rose daily, but life just kept getting worse the more alms we received. (p. 199)

As you can see from these excerpts, there is an occasional clumsiness in the English used by this author, who is Russian, but writes in English. I am curious about this decision: given the low rate of translation from other languages to English, perhaps it is a way of getting a wider circulation for his work?

The most tragic moments of this unremittingly sad tale come when the girls find a way to seek out their mother, but there is no happy ending. The book is a wake-up girl for all of us to interrogate the way we respond to diversity, perhaps best summed up by this comment:

“People have no limits either in love or in hatred. But is it their fault? They despise us because they are afraid, for we remind them that getting crippled or sick might happen to anyone; or, perhaps, the true reason for their hatred lies much deeper inside, stemming from a hidden ugliness in their souls?”

Author: Igor Eliseev

Title: One-Two

Publisher: Glagoslav Publications, 2016

ISBN: 9781911414230

Source: review copy courtesy of Glagoslav Publications

Available from Fishpond: One-Two or direct from Glagoslav Publications, including as an eBook

Looks right up my alley, thanks for the review, one to add to my TBR pile

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: tonymess12 on March 28, 2017

at 7:16 pm

It’s one you won’t forget… I’m still mulling it over…

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on March 29, 2017

at 4:09 pm

Very timely review for me – thank you, Lisa.

LikeLike

By: mairineilcreative writer on March 28, 2017

at 10:21 pm

Wait till you see the tunnels mentioned in the book: honestly, it’s like a whole world in those subway tunnels, some are almost like small shopping malls.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on March 29, 2017

at 4:10 pm

[…] One-Two, by Igor Eliseev (2015) […]

LikeLike

By: Russian Literature, a Very Short Introduction, by Catriona Kelly | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 10, 2017

at 6:54 pm

[…] Book With A Number In The Title: One-Two by Igor Eliseev. Ok, that’s two numbers but they are hyphenated. And that’s because […]

LikeLike

By: Reading Bingo 2017 | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 16, 2017

at 2:59 pm