What a pleasure it is to read Chaconne, the debut novel of Canberra author Diana Blackwood! There’s a serious coming-of-age story here, but the book is laced with delicious puns and droll set pieces and I loved the way Blackwood has subverted the clichés of the Romantic Paris genre.

What a pleasure it is to read Chaconne, the debut novel of Canberra author Diana Blackwood! There’s a serious coming-of-age story here, but the book is laced with delicious puns and droll set pieces and I loved the way Blackwood has subverted the clichés of the Romantic Paris genre.

She dressed neatly enough for Café Obertor and put on her walking shoes. While she was tying the laces, it occurred to her that any Parisian veneer she might have acquired was already slipping away. She no longer felt compelled to expend thought on her appearance if she wasn’t so inclined. In Paris she had almost always made some kind of effort because the city itself seemed to demand it: the scarf knotted just so, the jaunty accent of colour that showed you hadn’t thrown on your clothes in the half-dark but had put together a look in front of the mirror. Whenever she had left the building In Rue Dauphine, the buzzer, followed by the clunk and guttural moan of the door, would announce that she was now entering the theatre of the street and she had better be dressed for it. (Entering the building had been another matter: the buzzer might signal a return to the dishevelment of private miseries.) But in Hunsrück, as far as she could tell, it was enough to avoid looking like a homeless person or a scruffy remnant of the Baader-Meinhof gang (p.148-9)

The dishevelment of private miseries to which this excerpt refers is because of Julien. It is 1981 and Eleanor has left her unsatisfactory life in Australia to join a bourgeois communist called Julien in Paris. But Julien turns out to be a cad. (Sorry, I know that’s an old-fashioned word, but really, no other will do.) Eleanor is only twenty-four, and hopelessly naïve about him (and politics), and smile as you will at her misery over this man, you feel her pain. She has put up with so much because of him: squeezed into his microscopic flat that has no bathing facilities while he continues to live comfortably elsewhere; endured the luncheon from hell with his haughty mother for whom not being French is a social blunder impossible to rectify; succumbed to being intellectually patronised; and – for most of the time – stoically borne his long absences while he pursues his studies.

She should have known, of course, when he wasn’t there to meet her at the Gare du Nord.

Why had he not been waiting for her as he should have been, twitching with impatience and bursting with love? It was too soon to be angry, for anything might have happened, but it was the right time to feel cheated. (p.3)

Indeed.

The absence of a bath turns out to be pivotal. Roland, her nice (gay) neighbour in the adjacent apartment, has a bath, and he lets Eleanor use it when he’s away from home. The arrangement continues when Roland sublets the apartment to an American called Lawrence:

Even before he opened his North American mouth, she would not have taken the man for a Frenchman. Tall, sandy-haired, square-jawed , with a modest gingery moustache, he was wearing a ski-jacket and leather hiking boots, as if he had been traversing a snowy campus with his bag of groceries. (p.108)

Alas, Eleanor is not good at choosing men, and she should have known from the conversation that they have through the bathroom door that Lawrence was a bad idea. He is in Germany to earn an undemanding living while he finishes his self-imploding novel that he started when he was part-way through his PhD on deconstructive theory. Eleanor’s musings about what a self-imploding novel might be offer an opportunity for authorial punning while also poking fun at Lawrence’s pretensions:

‘Oh, you know, you write it and deconstruct it at the same time.’

‘Well, said Eleanor, who had no idea what he was talking about, ‘that could be tricky – like trying to have a bath while you let the water out.’

‘Hey, that’s a neat image.’

‘What’s it about, your self-imploding novel?’

‘It’s kind of a spy story, but of course it’s not about anything. I’m just playing intertextual games with the Cold War’s favourite genre and its grand narratives. I play with labyrinths of unstable meanings, the unravelling of meanings, aporia, the mass hallucination that is the Cold War. So as not to appear completely anti-humanist, I dangle a kind of resolution before the reader and then snatch it away at the last moment…’

Eleanor stopped listening, as a he was clearly not going to indulge her with a story. She felt weak and emptied of feeling. Occasional words penetrated the blear like fragments torn from a nightmare: linguistic predicaments, logocentrism – or was it logorrhoea? – chiasmus, Dasein, effraction, glissement… Glissement: now there was a word with a certain slippery allure. (p.111)

Eleanor becomes a sharper, wittier Dorothea to Lawrence’s Casaubon, and her departure for West Germany to be with him turns into a pragmatic marriage so that she can have a work permit to teach English grammar at his base. Oh dear, this is going to end in tears, thinks the older and wiser reader, when Lawrence sends her out shopping for a suitable dress for the wedding. Her purchase of a silk blouse instead isn’t entirely reassuring, and as the story progresses Lawrence becomes more of a bully, while Eleanor’s rebellions become more covert and internal.

Fortunately Diana has Ruth, a wise and funny friend who writes amusing letters from Australia. (We have to keep reminding ourselves, when we read stories from the recent past, that there was once a time without the internet, email, SMS and social media, eh?) And Eleanor also has music. She has not forgiven her mother for the fact that her piano lessons in childhood had to give way to maths tutoring, but she still has a beautiful voice and a passion for early English music.

Chaconne (fortunately) doesn’t have a conventional romantic ending, but Eleanor’s coming-of-age is highly satisfactory all the same. As many of us did in those early years of feminism, she discovers that she doesn’t need to submit to unreasonable behaviour, and she learns what she wants to do with her life.

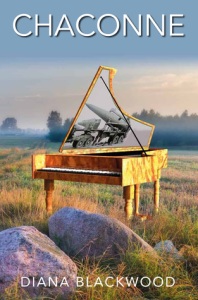

Observant readers will have noticed that disconcerting image on the lid of the harpsichord on the cover. The design is by Grant Gittus from Gittus Graphics in South Melbourne. (He also did that wonderfully moody cover for John Tully’s Dark Clouds on the Mountain). The missile is an allusion to the Cold War setting, and the presence of the US base on West German soil. We read Chaconne now knowing that the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, but Eleanor’s anxiety resonates with contemporary readers because we feel it too, living with the risk of mutually assured destruction due to political belligerence.

Here are two beautiful songs referenced in the novel… I attempt from Love’s Sickness to Fly by Henry Purcell:

And Now, o now I needs must part, by the less well-known Renaissance composer, lutenist, and singer, John Dowland

(I left John Dowland to transition from one YouTube music video to another as I wrote this post, discovering an exquisite lute pavanne as I did so).

In a bumper year of new release novels by Australia’s most prestigious authors, Chaconne is unquestionably one of the most enjoyable books I’ve read this year!

Tracy at Reflections of an Untidy Mind loved it too. (BTW This is Tracy’s first-ever review, and she writes a fine one – so do visit her site to encourage her to do it again!)

Author: Diana Blackwood

Title: Chaconne

Publisher: Hybrid Publishers, 2017

ISBN: 9781925272611

Review copy courtesy of Hybrid Publishers.

You can read a sample online at the publisher’s website. (BTW postage is free at Hybrid if you spend more than $40 so that makes buying two books rather irresistible IMO. Check here for my reviews of other books from Hybrid if you feel tempted and need some help to choose.)

Also available from Fishpond: Chaconne and wherever good books are sold.

I’ll read this later, when I’ve read my copy. I’m hoping to get to it in January.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on December 23, 2017

at 2:39 pm

You will love it, Sue, it’s just gorgeous. Do you know the author?

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on December 23, 2017

at 2:41 pm

No, I’d never heard of her until I received the book! We’re a small place, but clearly not as small as I thought!

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on December 23, 2017

at 3:26 pm

There’s so much more to this book than I’ve indicated here, I can’t wait to see what you think of it. She has such a wicked sense of humour:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on December 23, 2017

at 3:34 pm

That sounds good. I do like a wicked sense of humour. I can’t recollect where it is in my list – which, for some reason, I don’t keep online. About the only list I don’t, in fact. So, it’s in the other room and I’m too lazy to go check!!

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on December 23, 2017

at 3:36 pm

Ha ha, old age is creeping up…

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on December 23, 2017

at 5:04 pm

Lovely review, Lisa! A nice Christmas present for the author.

Regards Anna

LikeLike

By: ablay1 on December 23, 2017

at 3:13 pm

I feel as if I’m the one who had the present, I just want all my friends to read it so that we can talk about it together:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on December 23, 2017

at 3:35 pm

Thanks for the review. This one sounds interesting.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on December 23, 2017

at 4:16 pm

I love books to do with music:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on December 23, 2017

at 5:04 pm

This sounds excellent, I’ll have to come up with an excuse to buy it – no female birthdays until late in the year. Someone in Paris showed ex Mrs Legend how to knot a scarf just so. She and our 5 year old granddaughter wore perfect scarves for the rest of the trip

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on December 23, 2017

at 7:14 pm

I have failed scarf tying entirely. I think my shoulders are the wrong shape. Well, that’s my excuse…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on December 23, 2017

at 7:22 pm

Haha, I’m scarf-challenged too. Every time I fluke something I feel very proud of myself but mostly I go very simple – a long scarf just draped.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on December 23, 2017

at 8:36 pm

I loved this book too.

LikeLike

By: Reflections of an Untidy Mind on December 24, 2017

at 1:51 pm

Hello Tracy, thanks for dropping by:) I am impressed by your review so I’ve linked to it, as you can now see above.

Best wishes for the festive season, and happy reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on December 24, 2017

at 1:58 pm

Thank you, Lisa. And happy reading to you too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Reflections of an Untidy Mind on December 24, 2017

at 2:27 pm

[…] Chaconne (2017) by Diana Blackwood […]

LikeLike

By: 2017 ANZLitLovers Australian and New Zealand Best Books of the Year | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 30, 2017

at 4:23 pm

[…] (ANZLitLovers) loved this novel and includes two YouTube links to music referenced in the […]

LikeLike

By: Diana Blackwood, Chaconne (#BookReview) | Whispering Gums on February 24, 2018

at 11:54 pm

I enjoyed your review Lisa – and love that you included some examples of the music referenced. I love harpsichord and baroque music and enjoyed reading about a time when interest in that type of music was reviving. Took me back to the late 1970s and 1980s days when I first heard of Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music, and groups like this.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on February 25, 2018

at 8:29 pm

Oh yes, I remember someone giving me a recording of baroque music and falling in love with it from that moment onwards. Every year when we go to the Woodend Festival there is music from this period and it’s just heaven to listen to it live:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on February 25, 2018

at 8:43 pm

Sure is – heaven to listen to it live I mean!

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on February 26, 2018

at 8:46 am

Reblogged this on The Logical Place.

LikeLike

By: Tim Harding on June 9, 2018

at 5:32 pm