A female convict on the run in the Tasmanian wilderness in 1826? It doesn’t sound very likely, does it? But debut novelist Rachel Leary has managed to create a wholly convincing novel out of this inversion of the Intransigent Convict trope, and it’s breath-taking reading.

A female convict on the run in the Tasmanian wilderness in 1826? It doesn’t sound very likely, does it? But debut novelist Rachel Leary has managed to create a wholly convincing novel out of this inversion of the Intransigent Convict trope, and it’s breath-taking reading.

It’s historical fiction, but not as we might know it. While her style is different, in impact Bridget Crack is more like Rohan Wilson’s disconcertingly powerful duo The Roving Party and To Name Those Lost, also set in colonial Van Diemen’s Land when the new society being created is confronting both the hostile forces of the Indigenous owners of the land and the harsh environment. As in Wilson’s novels, the moral choices of Leary’s novel are trapped by pragmatism.

Everything is against Bridget. The pugnacious landscape, the cruel weather, the entire apparatus of the convict system – and her gender, which makes her doubly vulnerable because of the attentions of men in a society where women are scarce and mostly there for the taking. Psychologically, she’s ill-equipped for survival in a place where she is dependent on others for fundamentals like food and shelter: she’s impatient, impulsive and intolerant. She’s also poignantly naïve. Her initial placement is as an indentured servant in a comparatively benign Hobart residence, but – not knowing what to expect and having no idea about the realities of this crude, violent society – she finds it intolerable. It’s her own intransigence that lands her in a Hobart gaol for insubordination and thereafter on assignment to the interior far from any kind of rescue. Faced with a horrible man who lied to the authorities about having a wife so that he could be assigned a female servant, and who lets his other servant die without a qualm, Bridget runs away into the bush. Her naïveté shows in the theft of the items she takes with her: she takes no provision for water.

Inevitably, she gets lost. (As people so often do in the Tasmanian wilderness, even today, with GPS and mobile phones). But her rescuers are four brutal bushrangers, also convicts on the run from the authorities. The Sheedy gang gets by with raids on nearby farms and the reluctant help of shepherds and other absconders on the frontier. Of these four, Matt Sheedy is the Alpha Male, but he is no romantic hero defending Bridget’s honour against the lascivious attentions of the repulsive Budders or the doubts of Henry and Sam about the wisdom of a woman slowing them down. Bridget Crack is most certainly not a romance.

Travelling in their company changes Bridget’s status from absconder to wanted criminal, eventually with a price on her head. That price means that it’s not possible for her to trust anyone. She’s at the mercy of the bush, the killers she’s travelling with, and the soldiers who hunt her.

However, apart from the circumstances which led to her conviction in the first place, Bridget is not a victim, except of the weather.

This was no ordinary rain. It came across the sky in dark grey sheets, the drops barbed with ice. It punished the canopy, the ground, without mercy. This was weather of a new kind – weather with no name. Whatever it was it grabbed the trees and shook them with an unbridled madness that had them groaning, their smaller branches scribbling in panic while strips of bark were ripped from their trunks and flung to the ground.

She scrambled up a slope, her boots bloated with water, the dress sticking to her. A rock jutted out from the hill to form a shallow overhang, a space under it that she wedged herself into.

Daylight faded into pitch-black. Thunder pressed the hills. Lightning spilled across the sky, for a moment exposed the abused, bedraggled world below. Then everything was claimed by darkness again. She lay folded into the hole, watching, shivering. Somewhere close by there was a crash and her heart hammered her chest bone. The silence, when it came, was so thick it seemed to buzz.

For a while she slept then woke suddenly. Something near her shoulder, something there. The knowing of it sharp in her body. She didn’t breathe, kept perfectly still. It was close to her face now, blackness, darkness, whispering its ugliness. There was another clap of thunder, She pushed herself back against the dirt wall. (pp. 51-2)

Meanwhile back in Hobart, her former employer Captain Marshall is wrestling with his conscience. He admits to himself that he was attracted to Bridget, and he also knows that he could have prevented his spiteful wife from offloading Bridget for a trivial offence. So he bears some responsibility for her plight. Sent out to recapture her, he struggles with her moral culpability: has she willingly joined the bushrangers, or has her time with them been an unwilling matter of survival? The distinction is more than academic because bushrangers are hanged for their crimes; absconders spend a bit of time in the Female Factory doing hard labour and are then reassigned to a new employer.

The presence of the Indigenous people is skilfully handled. By 1826 they were being forced further and further away from their land, and they are about to be removed from the settled areas by the edict of Governor George Arthur stating that the military and settlers could use force to drive natives away from properties. (This was the infamous Black Line). The use of the military is new, but the violence is not – the hunter Sully has already witnessed the aftermath of a massacre by settlers:

That night he sat by the fire drinking cider. ‘This time,’ he said- and his voice was quiet and he leaned down and put his drink down on the floor – ‘I ain’t been in Van Diemen’s Land long. Were out hunting roo, few mile upriver from town. It were a windy day.’ He paused, squinted at the fire, and when he spoke again his voice seemed even more faraway. ‘I remember it were real windy. I come up this slope. Come to the top of the rise and I seen them there. I seen them. I knew what I were seeing. I knew it alright, but … sometimes you can see a thing, you know what it is, but you can’t figure it out. So I stood there. I just stood there.

Little kids and everything. The dogs sniffing at them. I turned round and just about run down the hill.

‘Blacks,’ he said. ‘All of them shot. (p.172)

Yet the Aborigines are not without agency, interacting in an exchange of equals with one of the shepherds in a remote area, surprising Bridget with their fluent English. They divert the soldiers from the gang’s trail, laughing off Primmy’s warning that they might get themselves in trouble:

‘Trouble?’ Trousers grinned. ‘Already in trouble.’

The irony of this comment is amplified by the exchange that follows.

‘He wants guns’, Sully said. He spoke to Primmy, said Trousers had asked him to get guns for him. ‘This hunting ground’s not yours,’ he said. ‘Told him I knew it wasn’t bloody mine. He says it’s theirs, gov’nor probably says it’s the king’s, some farmer’ll come out here with a piece of paper says it’s his, and not long now either.’ (p.171)

Trousers wants the guns because ‘Whitefella kill plenty blackfella […] Kill women, piccaninnies, and prophetically, Sully asks, ‘Do you think they’re going to stop killing you because you kill them?’

In a later episode Bridget encounters two hunters and surrenders a kangaroo caught by her dog, a metaphor for recognition of their prior ownership – a recognition that should have been exercised by colonial interlopers who are more powerful and more morally culpable than she is.

Bridget Crack is a stunning debut and I’m looking forward to seeing what Rachel Leary writes next!

You can find out more about Rachel Leary at her website.

Other reviews:

- Ellen Cregan at Kill Your Darlings (where the book has been chosen for their First Book Club)

- Ross Southernwood at the SMH

- Rohan Wilson at The Australian, but that’s paywalled.

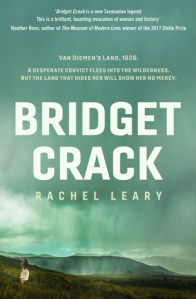

Author: Rachel Leary

Title: Bridget Crack

Publisher: Allen and Unwin, 2017

ISBN: 9781760295479

Review copy courtesy of Allen and Unwin

Available from Fishpond: Bridget Crack

Sounds like you had a good time with this one. I don’t read historical fiction (for me that anything beyond WWI) although I do make rare exceptions.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on October 31, 2017

at 1:27 am

I don’t read the historical fiction that’s given historical fiction a bad name. But good historical fiction written by clever authors with something thoughtful to say, that’s different.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 31, 2017

at 10:24 am

Sounds great! Yes I know it’s historical fiction, but it’s using the genre to explore what-if’s, in the way that SF does. In any case, though it is not often discussed, boys were probably in exactly the same situation as young women, sex objects and largely without agency.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on October 31, 2017

at 10:23 pm

I think you’d like it, Bill.

And honestly, the descriptions of the landscape and the weather are just exquisite. This author is a genius with words.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on October 31, 2017

at 11:10 pm

[…] regular readers will know, I recently read and reviewed Bridget Crack, the debut novel of Tasmanian author Rachel […]

LikeLike

By: Meet an Aussie Author: Rachel Leary | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 14, 2017

at 9:00 am

[…] Leary is a debut author whose historical novel Bridget Crack is getting rave reviews, (including mine). It’s the story of a female bushranger, set in the […]

LikeLike

By: Authors from Tasmania (Australian Authors #2) | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 6, 2017

at 10:20 pm

[…] Bridget Crack (2017) by Rachel Leary […]

LikeLike

By: 2017 ANZLitLovers Australian and New Zealand Best Books of the Year | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 30, 2017

at 4:23 pm

[…] first novel is Bridget Crack which I reviewed a little while ago. The book is published by Allen & Unwin, […]

LikeLike

By: Debut Mondays: new fiction from Rachel Leary and Louise Allan | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on January 8, 2018

at 9:01 am

[…] Bridget Crack by Rachel Leary, (Allen & Unwin), see my review […]

LikeLike

By: 2019 Tasmanian Premier’s Literary Prize shortlists | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on October 14, 2019

at 1:57 pm

[…] Bridget Crack by Rachel Leary, (Allen & Unwin), see my review […]

LikeLike

By: Island Story, Tasmania in Object and Text by Danielle Wood and Ralph Crane | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on November 18, 2019

at 12:32 pm