I stumbled on this little treasure at the Beaumaris branch of the Bayside Library service, and picked it up because it was a title I didn’t know. I thought I’d read everything there was to read of Waugh when I was in my twenties: one of my brothers-in-law loved Waugh’s subversive humour and over a blissful period of months he lent me every title he had. And he was a very rich BIL so he had, I had always thought, the lot. (I’ve always thought that it took some strength of character for my sister to divorce such a very rich man.)

I stumbled on this little treasure at the Beaumaris branch of the Bayside Library service, and picked it up because it was a title I didn’t know. I thought I’d read everything there was to read of Waugh when I was in my twenties: one of my brothers-in-law loved Waugh’s subversive humour and over a blissful period of months he lent me every title he had. And he was a very rich BIL so he had, I had always thought, the lot. (I’ve always thought that it took some strength of character for my sister to divorce such a very rich man.)

Anyway, although Waugh’s trademark humour makes this a distinctive work, Helena is not anything like A Handful of Dust or Brideshead Revisited or any of the other droll masterpieces of social commentary that you’ve heard of. It is a novella of just over 200 pages, and it’s historical fiction – a fictionalised life of Helena, Empress of the Roman Empire and the mother of Constantine the Great who reigned from 306–337. The Catholics (and Waugh was a Catholic) made her a saint because she purportedly discovered the True Cross, the one on which Jesus was crucified.

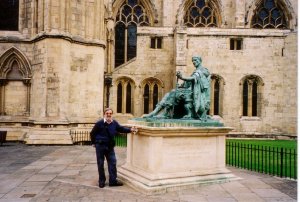

The Spouse admiring the statue of Constantine the Great at York Minster

As Waugh acknowledges in his brief and witty introduction, not much is known about Helena even though she was such a profound influence on her offspring that he was the first emperor to desist from persecuting the Christians, he issued the Edict of Milan which allowed them to practise their faith without being fed to the lions, and he prudently got himself baptised on his deathbed, thereby cleansing his soul of a lifetime of sins just in time for entry to the Pearly Gates. The Brits have acknowledged his pivotal role in establishing Christianity and Western Civilisation &c with an imposing statue at York Minster, because it was in York that his soldiers rebelled against the expectation that another Caesar would become Emperor and proclaimed him their leader instead.

Constantine and Helena. Mosaic in Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, Peterburg, Russia

So what? you may be thinking. What makes this a worthwhile book to read? Well, for a start, it’s always a good thing to have the role of women acknowledged in history, even belatedly. And secondly, loosely based on the vaguest of historical fact, it allows Waugh full reign to create a most interesting story, enabling a critique of the excesses of the age which counters versions of Imperial Rome that focus more on murder and mayhem than the problem of political corruption and governance.

And it’s often droll, with surprisingly sensitive portraits of women in an era when men have so successfully hogged the limelight. Helena is a plain, horsey girl enjoying reading Homer’s Iliad with her tutor Marcias, when she attracts the attention of Constantius when he is deployed as a junior officer in Britain. The marriage begins well but after the birth of her only child Crispus, Constantius’s ambitions take over and she is neglected for long periods of time. Helena however does not mope. She makes a life for herself, farming in Dalmatia and sustaining her father’s contempt for Roman politics. Other female names from Imperial Rome surface too. Long-neglected Calpurnia has a cameo role as a friend to Helena in her latter days when Constantius had strategically divorced her, and even the manipulative Fausta seems more of a victim of circumstance. (Though as Constantine belatedly realised after she made him authorise the murder of his first-born son Crispus, she went too far when she tried to blame Helena for it.)

All the dramatis personae of the Imperial Story have a human face. Constantine, who had to wait a very long time for his elevation to power, gets a bit peevish over the matter of his Triumphal Arch. By the time it comes along, modern artists have control of proceedings, and the Office of Works rejuvenating Rome has hijacked the labour force. After twelve years of not-so-patient waiting, Constantine inspects the triumphal arch which they claim to have finished, and is not best pleased.

‘I went there myself yesterday to look at it. It is not finished.’

‘Certain decorative applications…’

‘Certain decorative applications. You mean the sculptures.’

‘We meant the sculptures, Sir.’

‘That’s precisely what I want to talk about. They are atrocious. A child could do better. Who did them?’ (p.137)

Titus Carpicus, with mild patience, does his best to persuade the Emperor:

‘…The arch, as conceived by my friend Professor Emolphus here, is, as you see, on traditional lines, modified to suit modern convention. It is, you might say, a broad mass broken by apertures. Now this mass involves certain surfaces which Professor Emolphus conceived had about them a certain monotony. The eye was not held, if you understand me. Accordingly he suggested that I relieve them with the decorative features you mention. I thought the result rather happy myself….

Constantine is Not Happy that none of the sculptures remotely resemble him, describing them as lifeless and expressionless as dummies. He’s seen better work done by savages. The horses look like children’s toys. There is no grace or movement in the whole thing. He refers Carpicus to Trajan’s Arch (at Ancona), which is dismissed as good of its period. Not perhaps the best.

Carpicus tactfully suggests Trajan’s other Arch at Benevenuto is definitely attractive but Constantine (who’s never seen it) is not interested. Like many a man who knows what he likes when it comes to art, he has a fixed idea in his mind, and he knows he doesn’t like ‘modern art’. Fausta weighs in to tell him that Trajan’s Arch was built more than two hundred years ago and he can’t expect one like that ‘today’ – and gets the kind of response you might expect from an exasperated emperor.

‘Why not?’ said Constantine. ‘Tell me, why not? The Empire’s bigger and more prosperous and more peaceful than it’s ever been. I’m always being told so in every public address I hear. But when I ask for a little thing like the Arch of Trajan, you say it can’t be done….'(p. 140)

Hmph, says Carpicus with poorly concealed disdain, he could contrive a pastiche…and that’s exactly what Constantine got, as you can see if you read the description at Wikipedia.

Well, Helena got no arch, or much else in the way of recognition, but her legend is that in her old age, when as Waugh has it, she was a crank, she set off on a pilgrimage in 326 and caused all manner of inconvenience in Aelia Capitolina a.k.a. Jerusalem because her arrival conflicted with an influx of Christian pilgrims and a building program.

Here, as elsewhere, little was known of the Empress Dowager. She was a golden legend. They expected someone very old and very luxurious; and, they rather hoped, gentle. Instead, they met a crank; and more than a crank, a saint. It was altogether too much. They were prepared to meet demands for delicacies of the table and elaborate furniture. They had secured a quite passable orchestra from Alexandria. What Helena wanted was something of a quite different order. She wanted the True Cross. (p. 183)

Using skills worthy of any modern-day female detective, she interrogated all and sundry, dismissing most of what she hears with an emphatic Rot! or Bosh! but she finally locates the site in a dream and triumphantly takes most of the cross back to Rome with her, where it joins any number of relics of bones and teeth and other bits and pieces that you can find in reliquaries all over (what was) Catholic Europe.

If you like your saints strong-willed and unsentimental, Waugh’s Helena is the one for you!

*Photo credits:

- Photo of the mosaic at St Isaac’s in St Petersburg by collective of mosaicist of Saint Isaac’s Cathedral – http://www.uer.varvar.ru/sim-pobedishi.htm, Public Domain, Wikipedia Commons

- photo of Trajan’s Arch By Decan – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia Commons

- photo of Trajan’s Arch at Ancona by MarkusMark – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikipedia Commons

- photo of the Arch of Constantine in Rome by Livioandronico2013 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia Commons

Author: Evelyn Waugh

Title: Helena

Publisher: Penguin Classics, 2011, first published 1950

ISBN: 9780141193502

Source: Bayside Library

Out of print, I think. This title is No 18 of a series of 24 hardback editions of Evelyn Waugh titles, forming a ‘library’ of his work.

Reblogged this on The Logical Place.

LikeLike

By: Tim Harding on August 20, 2018

at 1:10 pm

I hadn’t heard of this one- sounds like a good one. Great review!

LikeLike

By: mrbooks15 on August 20, 2018

at 2:20 pm

Thank you! (It makes one wonder whether there are other Waugh treasures to be tracked down….)

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 3:53 pm

This sounds rather interesting! Thanks for such a great review on it, I was quite entertained!

LikeLike

By: Theresa Smith Writes on August 20, 2018

at 4:28 pm

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 6:38 pm

Fantastic, LIsa. I hadn’t read it either and like you, I thought I had read everything of his, but one should never think that of someone like Evelyn! I really enjoyed the review & laughed at your intro too! The Loved One was another great read.

LikeLike

By: Jan Wallace Dickinson on August 20, 2018

at 4:38 pm

Ah yes, you know, I’m thinking I should revisit Waugh…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 6:40 pm

What a gem to find and especially given you’d read so many of them, riveting review indeed!

LikeLike

By: Claire 'Word by Word' on August 20, 2018

at 6:00 pm

And now, thanks to the wizardry of the net, Bill tells me (below) about another one I hadn’t read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 6:41 pm

My first Waugh was another Catholic history, the life of English saint, Edmund Campion. It’s 55 years since I got it and probably almost that long since I’ve read it, but I was impressed at the time.

LikeLike

By: wadholloway on August 20, 2018

at 6:19 pm

Another one I didn’t know about! Thank you, I’ve just ordered it:)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 6:44 pm

I’ve been looking for books that a Catholic customer of mine might like – shame this one seems to be OP, as it’s pretty perfect!

LikeLike

By: Elle on August 20, 2018

at 7:28 pm

Maybe Abebooks has a copy…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 8:02 pm

I’ve just found that the old Penguin Modern Classics paperback edition (from 1990) is still in print!!

LikeLike

By: Elle on August 20, 2018

at 9:38 pm

Excellent! Do they have others in the series too?

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 9:58 pm

Not clear – I’ve just found the result on Nielsen when I searched the title/author combo.

LikeLike

By: Elle on August 20, 2018

at 10:58 pm

How very interesting. I hadn’t heard of this either, but I agree completely with your argument about why it was worth writing. We need all these women’s stories to be out there – in historical fiction and histories – alongside the men.

BTW Your comment that “(I’ve always thought that it took some strength of character for my sister to divorce such a very rich man.)” made me laugh. Good for her, eh, if she wasn’t happy?

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on August 20, 2018

at 8:14 pm

Yes, and I think that historical fiction of the intelligent (i.e. not bodice-ripper) variety is a very effective way to bring these lights out from under the bushel. Because so often the documentary record is a bit feeble and an imaginative well-researched novel is a great way to give these women a voice and a presence that they otherwise couldn’t have.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 8:51 pm

Couldn’t have said it better myself – now we just have to get Bill to see it!! (Listening Bill?)

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on August 20, 2018

at 9:08 pm

I’m listening. My objections are to the ‘modernising’ of Australian history. Writers can do what they like with olden times. I do find it amusing though that you are so welcoming of that old curmudgeon Waugh. As a Catholic convert he had a very orthodox view of the saintliness of saints.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: wadholloway on August 20, 2018

at 9:18 pm

Well we are in furious agreement when it comes to modernising… women behaving like Bolshie feminists mostly doesn’t work IMO. But women *wanting* to have more options, economic independence and so on, that’s a different thing (as you can see in the fiction of Catherine Helen Spence and others like her.

But Waugh’s Helena is not very saintly at all. She does pray, but not very often, and she’s not very good at saintly forbearance either!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 10:03 pm

This article says it much better: what other kind of writing can so eloquently tell the stories of silenced voices in colonised Africa? https://johannesburgreviewofbooks.com/2018/05/07/historical-fiction-is-back-with-a-fire-in-its-belly-fred-khumalo-reflects-on-how-writing-can-be-a-powerful-tool-for-an-activist/

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 10:08 pm

Thanks, I’ll check that out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: whisperinggums on August 20, 2018

at 10:41 pm

Gosh, I’d not heard of this Waugh at all but strong women in history? Sounds essential!

LikeLike

By: kaggsysbookishramblings on August 20, 2018

at 8:47 pm

Isn’t it amazing?! Such a famous writer and we are still discovering little treasures…

It makes me think…

Before the internet, and Goodreads and Wikipedia in particular, it was hard to know about an author’s entire output. The bookshops had this, and the library had that, and there was nowhere else to look it up unless you were a real devotee and had books like The Oxford Companion. But even those had their limitations – they were Britcentric and male-dominated and the literature of countries like Australia was only ever a token presence and translations didn’t get a look in at all. It’s just so blissfully different now!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on August 20, 2018

at 8:59 pm

I’ve not heard of this one either! I have mixed success with Waugh, but this one certainly sounds interesting and unusual.

LikeLike

By: Simon T on August 20, 2018

at 10:44 pm

I liked it especially because at uni I did Classic Greece and Rome (art, lit & history) and (as you can tell from my images) I could relate to the period.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 21, 2018

at 3:43 pm

I hadn’t heard of this one either though it’s listed on the Wikipedia bibliography. Is it humorous or pretty straight?

I recently read The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold which was a fun read. Have you read it?

LikeLike

By: Jonathan on August 20, 2018

at 11:05 pm

It’s not laugh out loud funny, but the dialogue is usually pretty droll and it’s recognisable as a Waugh by the things he pokes fun at. And no, I haven’t read The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold – that sounds like one I must track down – this is such fun, discovering new titles!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on August 21, 2018

at 3:45 pm

As I researched medieval saints’ legends in an earlier part of my life I’d been aware of this title for some time but never got round to reading it – or the Edmund Campion mentioned above. I suppose I’ve always preferred these stories in collections like the medieval Legenda Aurea, or Golden Legend (I notice that title smuggled into one of the quotations you give – cheeky of him). If you liked this, you might be interested in Michèle Roberts’s Impossible Saints – not sure if that one’s in print now either – in which she re-tells stories of a number of saints (all women, if I remember rightly) in a way that’s very liberal with historical ‘facts’, rather in the manner of Angela Carter.

LikeLike

By: Tredynas Days on August 21, 2018

at 12:17 am

Ah, I didn’t get the allusion to the Golden Legend – thank you!

Something that occurs to me now, is that saints are supposed to have done a miracle, (or is it three?) in order to qualify under the Vatican rules I don’t think Waugh mentions a miracle in connection with Helena, and (dammit) I just returned the book to the library today so I can’t check it to be sure.

It’s mildly relevant because Waugh, it seems to me, is quite light-hearted in his treatment of Helena’s sainthood. He’s much more interested in her life. Perhaps he had a convert’s scepticism about the saints’ side of things?

Which makes me think (somewhat peevishly), why don’t I have a bio of Waugh on my shelves?!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 21, 2018

at 3:53 pm

The history of canonization is quite complicated; the article on Wikipedia gives a pretty good survey. Essentially it was originally just martyrs, then ‘confessors’ were added to liturgy and litany in the catholic church; not until the 12C did papal authority become the only route to official sainthood. The various criteria like miracles were added over the centuries that followed. Legends like St Helena’s were typical of those that arose in the early stages of Christianity – arising out of folk veneration, folk lore and local practice. It can be instructive to compare the narrative structures and components of saints’ lives with folktales (at the risk of upsetting the devout, perhaps). A common feature of early legends of saints included tropes along the lines of: ‘I don’t know for sure if the miracles that follow really were performed by St X, because records don’t exist; it has been necessary, therefore, to dip into those documented in other saints’ lives – for they are all capable of such acts, and they give rise to devotion which is their due’ – brilliant. Sort of hagiographical fake news.

LikeLike

By: Tredynas Days on August 21, 2018

at 9:51 pm

I had a teacher once who got me a bit interested in such stuff. He pointed out the commonalities between visions and hearing voices and the types of mental illness which are diagnosed these days.

I’ve always thought it’s a bit unfair to have to do miracles as well. Surely being a super-good person ought to be enough, given the attractiveness of most temptations, that is…

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on August 22, 2018

at 8:07 am