Elon Musk. Hmmm.

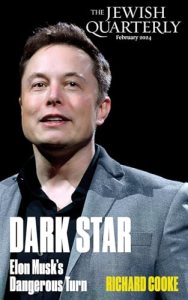

I like long form essays about current issues, and having discovered interesting things to read in the Jewish Quarterly lent to me by a friend, I succumbed to subscribing to this journal when they made the decision to change to long form essays. The first one to arrive in my letter box was Dark Star, Elon Musk’s Dangerous Turn by award winning author, reporter and screenwriter, Richard Cooke.

His website tells me that Cooke is:

The author of two books, Tired of Winning, A Chronicle of American Decline, (which has a picture of That Dreadful Man on the cover) and a work of literary criticism in the Black Inc series on Australian writers: On Robyn Davidson. He’s also the former US correspondent and current contributing editor to the The Monthly magazine, the former sports editor of The Saturday Paper, and the former arts editor of Time Out Sydney. For a time he edited The Chaser newspaper, and has been published in the Washington Post, The New York Times, The Guardian, The New Republic, WIRED and the Paris Review.

In other words, his interests range far and wide. He’s certainly a compelling writer: what he has to say about Elon Musk and his ambitions sent a chill down my spine…

He has a habit of inserting himself into major events to which he has little connection. (p.19)

We in Australia certainly remember how he tried to intervene in the rescue of those Thai schoolboys trapped in a flooded cave in 2018, offering to design a submarine to rescue them and insulting the leader of the rescue operation in a disgraceful way. But that is not the least of it. Other interventions have been much more alarming, with real world effects…

In the early phase of the war in Ukraine, Musk responded to a personal appeal from the Ukrainian vice prime minister by enabling the Starlink electronic system to replace the damaged telecommunications infrastructure within 24 hours of being asked to do it.

It was significant, and canny, that Fedorov made his appeal in public, but not everyone was impressed. ‘In that moment, Elon Musk, the man, seemed to be acting almost like a state of his own, a foreign entity that people around the world can call on for humanitarian aid in the way they might call on a government,’ Marina Koren wrote in The Atlantic, before offering some comfort. Musk’s ‘outsize reputation’, she assured readers, ‘doesn’t always match what he can actually control.’ Internally at SpaceX, the company’s president Gwynne Shotwell, argued that the private subsidy of the Ukrainian war effort was a mistake. She was negotiating a US$145 million contract with the Pentagon, which would fund Starlink on behalf of the Ukrainians, and was exasperated when Musk decided to continue on regardless. (p.20)

And then [as if Musk were a grown-up kid role-playing the computer game Civilisation], it was revealed that he had placed limitations on the technology which actually affected military operations. When the Ukrainians protested, Musk told them that ‘Starlink was not meant to be involved in wars. It was so people can watch Netflix and chill and get online for school and do good peaceful things, not drone strikes.’ (p.21)

Whatever the rights and wrongs of that or any war, it creates more than an uneasy feeling when a lone individual with massive wealth who does not hold public office can make decisions like that, eh?

Some called it treason. Musk was, they said, undermining the US State Department’s policy on Ukraine. Others attacked the lack of wisdom that had granted him these powers in the first place. Other European militaries began an urgent search for a Starlink alternative so as not to find themselves in the same position. […]

Musk’s own admission — that Starlink had been geofenced for the whole war — had serious implications. It meant Musk could not only end the advance of a foreign military with a word, but also set the shape of that advance beforehand, making hard boundaries for the conflict, by himself and in secret. Few individuals have been so central to a war effort since the duelling atomic physicists of World War II. Whatever was happening on the ground, Musk controlled the upper limits of the sky above it. (p.22)

Belatedly, US officials began to complain about American dependency on Musk, ranging from the future of energy and transportation to the exploration of space.

They mentioned that Musk also controls the largest nationwide network of electric vehicle chargers in the United States, making him critical to the future rollout of EVs, whether they are Teslas or not. (p.23)

[There are now four EVs on my route round the block with Amber, three of them Teslas. They charge up at home from rooftop solar with storage batteries. They’d be Tesla too.]

And while Ukraine was calling on Elon Musk, Elon Musk was calling for advice from his Twitter followers, and the one who suggested taking Starlink offline to de-escalate the war was a Malaysia-based political commentator called Ian Miles Cheong, whose massive audience consists of American conservatives.

For centuries, diplomacy rested on carefully attuned language. Diplomats were expected to be shrewd and wise, schooled in history and languages. It goes almost without saying that a sh__-posting social media account is the opposite of all this, making a mockery of it. And yet thanks to Elon Musk, figures like Ian Miles Cheong have more purchase on international affairs than the editors of Foreign Affairs. What is apparently trivial or unserious is in fact deathly serious. Because of Starlink, a poster in a Kuala Lumpur bedroom is directly linked to the Ukrainian front lines.

The language of power still treats internet chatter as beneath consideration, unimportant almost by definition. Like the Ukrainians, we find ourselves suddenly surprised: it is social media, not cable or newspapers or conclaves, that now sit at the epicentre of power. Like it or not, the first internet troll tycoon defines an era as much as the first internet troll president of the United States. (p.24)

The tech elite subscribe to a set of right-wing, hierarchical beliefs described by the acronym TESCREAL, which stands for Transhumanism, Extropianism, Singularitarianism, Cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altriuism and Longtermism. Unpacked, these ideas sound like something out of SF fantasy. [Merely researching some of the ideas behind Musk’s ‘philosophy’ has taken me to some very odd places online, and I stopped looking because (as we all know) we are tracked everywhere we go online by advertisers… and who knows who else?] But from Cooke’s article I gathered that Musk playing around with interplanetary ambitions and a new space industrial revolution is not just a matter of thousands of his Starlink satellites colonising Mars to create a new society over which he has full control. The longtermism of TESCREAL is concerned with prophecy:

…what will best secure humanity’s future existence and flourishing for the longest possible time? Humans must become immortal, or reach great longevity, and to do this they must leave Earth behind, for it is mortal. […] Musk dwells on existential risks to the human species, such as nuclear weapons or artificial intelligence […] Extreme longtermism can appear callous or unempathetic, prioritising trillions of hypothetical ‘future humans’, some born billions of years in the future, over suffering in the here-and-now.

His commitment to extreme versions of free speech without constraint can be seen from Twitter. Just as Murdoch withstood decades of massive losses from The Australian newspaper that makes no pretence of editorial independence because it exists to buttress his political influence, Twitter a.k.a. X has cost Musk billions. Cooke says that Elon Musk supports the abhorrent neo-Nazi views expressed on Twitter because he agrees with them, and the people who hold them and that he purchased Twitter in part to promote and protect them.

Scary stuff.

Update, the next day: Richard Cooke is writing a book about Wikipedia, and you can listen to a fascinating interview about that here at Down Round.

Author: Richard Cooke

Title: Dark Star, Elon Musk’s Dangerous Turn (Jewish Quarterly Feb 2024)

Edited by Jonathan Pearlman

Publisher: Morry Schwarz, 2024

ISBN: 9781760644345, pbk., 86 pages

Source: Subscription.

Interesting and scary all at the same time. I feel like, just as political totalitarianism was the huge issue of the 20th century, tech totalitarianism will be the big issue of the 21st century. People like Musk have way, way too much power with far too little oversight. It’s depressing to witness.

LikeLike

By: RussophileReads on April 10, 2024

at 11:34 pm

Yes, exactly. It’s what I hadn’t realised until I read this book. I had, shall we say in an understatement, a poor opinion of Musk, but I hadn’t realised the Big Picture implications of what he was doing. I could visit my carefully curated corner of Book Twitter where nice people talked about books, and I could read the headlines about his antics in Thailand. I could shake my head in dismay at the way he was wasting money on his little boy space adventure to Mars when people were going hungry here on Earth, and I could even admire the way he built a solar energy system in South Australia. But I had no notion of tech totalitarianism, none at all, and no idea what it could mean for all of us.

You know, when I was a young woman in the days when TV programming offered brain food, I heard a political pundit say that the biggest threat to the world was fundamentalism. At the time, here in Australia we knew only of Odd People in America who didn’t believe in evolution and of the ousting of the Shah of Iran which *smacks forehead* we thought was decolonisation, so his prediction fell on deaf ears here. But he was right. I fear that you and the author of this book are right about tech totalitarianism and that once again the horse has bolted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 9:14 am

Absolutely, and the fact that he and other tech titans like Zuckerberg are often treated either reverently as “innovators” or as some kind of harmless joke/eccentric instead of being truly analyzed for what they are and what they do in this world is truly awful to witness. Your comment about the “little boy space adventure” made me chuckle but it’s also dark because it’s so true: these people are trashing and controlling our planet, our media, our democracies, our futures, and acting like they own even the universe, and we just sit back and let them? We need some hard pushback, and we need it NOW.

LikeLike

By: RussophileReads on April 11, 2024

at 8:43 pm

Cooke writes at some length about how some people think he’s funny. It’s quite chilling to read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 10:18 pm

Scary indeed.

LikeLike

By: mallikabooks15 on April 11, 2024

at 12:31 am

Meanwhile our political leaders are trading barbs over low-level populist nonsense…

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 9:22 am

Don’t get me started on ours; we’re just starting elections next week and the level of acrimony as well as the barbs get to one each time one turns on/reads the news.

LikeLike

By: mallikabooks15 on April 14, 2024

at 12:54 am

And the media, words fail me. We’ve woken up here on a Sunday morning to the news that Iran has launched a drone attack on Israel i.e. a major escalation, and our live media isn’t even reporting on it. I’m watching the BBC to find out what’s going on!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 14, 2024

at 8:43 am

Ours are too busy accusing each other (different sections of the media, channels and such) or being too pro or too anti the current government so news anchors often become as partisan in debates as the guests they invite.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: mallikabooks15 on April 15, 2024

at 11:10 pm

Yes, I was thinking of this, this morning, when my neighbours woke me at 6:00 am again. I could put the radio on to give my brain something else to listen to, but the radio stations I used to listen to are such rubbish these days, they’d be more irritating than my neighbour’s (illegal) heating system.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 16, 2024

at 7:02 am

I haven’t listened to the radio for ages myself; we turn on the news every day of course, in fact multiple times, but sometimes one can’t help bt feel exasperated, or even like laughing when it gets even beyond that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: mallikabooks15 on April 17, 2024

at 12:13 am

Very scary – can’t bear the man and I think this might unsettle me and make my blood pressure shoot up…

LikeLike

By: kaggsysbookishramblings on April 11, 2024

at 1:25 am

My reaction too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 9:23 am

This sounds terrifying.

LikeLike

By: madamebibilophile on April 11, 2024

at 1:35 am

The number of satellites is breathtaking. (I’m old enough to remember Sputnik!) SpaceX has apparently sought permission to launch 42,000 satellites in all, begging the question, what will he do if he doesn’t get permission? Buy an island with its own launch station??

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 9:25 am

Don’t get me started. And as for TWATTER– oh I forgot…X which sounds like a porn hub, and actually … now that I think about it….

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on April 11, 2024

at 2:25 am

What dismays me about my own use of Twitter is that being able to curate our own feeds so that we are insulated from the nasty stuff, I have been blind to what’s going on there.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 9:27 am

A review copy platform used to post the reviews there (my reviews) but then apparently it became cost prohibitive after the ownership. I don’t go on it at all.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on April 11, 2024

at 9:30 am

I think I may have said this before. I used Twitter only to post a link to a new review, but I was thinking of joining the exodus, and experimented with not Tweeting there about new books. When I tweeted that I was toying with leaving, I got feedback that some followers relied on it to know about new reviews. They were busy folk, academics and publishers, who didn’t want to subscribe because (I guess) their inboxes were too full already and they wouldn’t have wanted to read every new post anyway. So I stayed. With misgivings.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 9:35 am

I’m too lazy to keep up with all that. I let the publishers/review platform post, and since they exited, well I’m off too. BUT I would have exited too if I had been involved at all before the purchase.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on April 11, 2024

at 9:42 am

The thing is, neither of us have a commercial imperative. We don’t need Twitter to keep our stats up to impress or create influence that has a dollar value. But (I’m guessing) that authors or publishers who’re trying to create momentum for a new book, it’s harder to make a ‘pure’ choice.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 10:21 am

I quit Twitter two years ago… account deleted completely… because I refuse to support [LH edit: him]. LOL.

LikeLike

By: kimbofo on April 11, 2024

at 12:19 pm

Fair enough too. But as Shaharee says below, it’s the system that has allowed him to emerge with the power that he has. And even when we as individuals disengage, the bigger problem remains.

That’s why I was interested to see that the government is promoting local manufacture of products where we don’t want to be reliant on outside forces that may be beyond our control. We discovered this with pharmaceuticals during the pandemic. What if South Australia comes to rue having a Tesla system running its power supply?

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 12:30 pm

Too pricey for the review platform to keep up with the new charges.

LikeLike

By: Guy Savage on April 11, 2024

at 2:57 pm

Its not the man we have to put in question, but the system that allows such an accumulation of power and wealth into the hands of one individual.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Shaharee on April 11, 2024

at 12:01 pm

Yes, and not just in this case either. Whether immense wealth is used for benign purposes or not, it represents an unfair system. Bill and Melinda Gates get Brownie points for their vaccination programs in Africa, but there are homeless people going hungry in the US and if the taxation system taxed the mega rich, something could be done about that and still leave money left over for philanthropic programs in the rest of the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 12:38 pm

The system isn’t going to change as long as billionaires can buy senator seats or the presidency of the US. It’s sad to say, but change will be brought to us when the debt bomb of 400 trillion USD that lays under the US federal reserve explodes and the world’s monetary system collapses.

LikeLike

By: Shaharee on April 11, 2024

at 1:26 pm

I do struggle to understand how in my lifetime we have gone from a system that was reasonably fair in the west, with flaws, the biggest and most egregious being that it wasn’t fair to what we are now calling The Global South, to completely unfair everywhere, with no resolution in sight.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 1:35 pm

The previous aristocratic world order has not been resolved in a fair way, but dissolved through an implosion of the deeply indebted aristocracy and the ensuing agro-industrial revolution.

LikeLike

By: Shaharee on April 11, 2024

at 1:50 pm

LOL Shaharee, we’ve never had an aristocracy in Australia.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 4:41 pm

No, You had aboriginals who were killed by the convicts that the UK sent to its penal colony. So most people in Australia have ancestors who were sent there by the British aristocracy as a punishment.

LikeLike

By: Shaharee on April 11, 2024

at 7:10 pm

Whoa!

For a start, the convict ancestry of some Australians has nothing to do with the fact that there never was an aristocracy here, indebted or otherwise.

And while you are correct about massacres that took place mostly on the frontiers, the British Colonial Office sent frequent (well-documented) demands to the colonial government that they put a stop to this illegal behaviour.

Furthermore, the Australian population is much more diverse than you might think. It is an immigrant nation: 30% of Australians were born overseas and many more have one or both parents born overseas. These migrants come from Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas — all over the world really — not just the UK. The top ten countries of birth were the UK, India, China, New Zealand and the Philippines, Vietnam and South Africa, Malaysia, Italy and Nepal.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 8:22 pm

Hi Lisa, you might be interested in Here Be Monsters: Is Technology Reducing Our Humanity? by Richard King, a local Fremantle writer. It’s a fascinating account of technology’s rise, particularly since the advent of social media, and explains in easy to understand terms how it is destroying society and our own humanity. It’s published by Monash University Press, so probably cheaper to borrow from the library. I think there’s probably a lot of crossover with the issues/themes you mention in your review here.

LikeLike

By: kimbofo on April 11, 2024

at 12:23 pm

LOL Kim, your timing is a little bit out! If only we’d had this conversation yesterday!!

I’ve reserved it just now from the library, and I’m going to the library in an hour or so for Book Chat, but *drat* the book is at a different branch so it won’t be there for me to pick up today.

Which means, *shock, horror* though I take pride in reducing my car usage, I will have to make a second trip to that library which is 8km away so beyond my walking distance.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 12:44 pm

Oops! But at least you can get the book. Be warned, the tone of voice is sometimes a bit off (he’s not shy about how he describes Trump, for instance, and he’s also scathing about Musk, but I think the points he raises are valid.)

LikeLike

By: kimbofo on April 11, 2024

at 12:55 pm

Yes, it’s tricky when reviewing a book like that. I’ve assumed that the publisher has done the legals for Cooke’s book, but I am monitoring comments about Musk here, in case anything gets said that is defamatory. (Apologies, but I’ve just realised that I need to edit your comment.)

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 1:17 pm

I understand (but I think it could easily be proven in a court of law… you just have to look at what he says and does and the way he treats and talks about women🤷🏻♀️😂)

LikeLike

By: kimbofo on April 11, 2024

at 2:49 pm

True. But it’s expensive and stressful to end up in court, so I’m careful.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 4:39 pm

I dislike him with a passion, but thanks for reading this (so I don’t have to)! Doesn’t sound like it would change my mind about him, either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Davida Chazan on April 11, 2024

at 8:56 pm

*chuckle*, it’s all part of the service, Davida!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By: Lisa Hill on April 11, 2024

at 10:18 pm

Great discussion Lisa … I wasn’t aware of this level of potential for tech totalitarianism. I don’t feel hopeless about it because I always have hope. That’s not always wise I know but technology offers so much opportunity for good, starting with the ideas that we are now getting to share with people around the world we would never have met.

I agree with you though about being gob-smacked about the way the world has turned since those heady, hopeful 60s. My initial reaction was to want to not believe it, but age (aka experience) has taught me that human nature is not always pretty and it has the upper hand. I see laws, overall, trying to edge towards more fairness and equity – and I say that with a grain of salt – but I see human beings, including those who have the wherewithal (that is, who are not fighting for survival) to be better, behaving so poorly.

As for the Gates foundation’s decision, I often think about Singer’s theories about who to help first, and while I don’t always agree with him, my inclination is to support any humanitarian philanthropy. Do we know what they do at home? With our own personal giving, we mix national and international humanitarian causes. That could be called into question – and of course we are talking crumbs not mega-cakes – but I think about the balance each year.

LikeLike

By: whisperinggums on April 12, 2024

at 8:25 am

I think we can all support humanitarian philanthropy while also feeling uneasy about the emergence of wealth which eclipses the GDP of many nations and enables pet projects without restraint or democratic control. Coming back to the book, some pet projects are ok, noble even, but clearly some are not, and if they are not benign but rather malevolent (think Bin Laden, for example) that is cause for concern, even if you are an optimist!

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on April 12, 2024

at 11:03 am