I haven’t quite finished reading Bold Palates: Australia’s Gastronomic Heritage yet, but I wanted to post about it today because (a) Masterchef is back on TV (hurray!) and (b) it’s Mother’s Day on Sunday and it might be just the thing for someone’s mum.

I haven’t quite finished reading Bold Palates: Australia’s Gastronomic Heritage yet, but I wanted to post about it today because (a) Masterchef is back on TV (hurray!) and (b) it’s Mother’s Day on Sunday and it might be just the thing for someone’s mum.

(In this household, however, the book is likely to be appropriated by The Spouse, who loves cooking and does nearly all of it. Except for the Christmas turkey, Pud & shortbread; jams, marmalades and sauces; and my famous vegetarian lasagne, which I refuse to surrender).

This is the blurb:

In Bold Palates Professor Barbara Santich describes how, from earliest colonial days, Australian cooks have improvised and invented, transforming and ‘Australianising’ foods and recipes from other countries, along the way laying the foundations of a distinctive food culture.

What makes the Australian barbecue characteristically Australian? Why are pumpkin scones an Australian icon? How did eating lamb become a patriotic gesture?

Bold Palates is lovingly researched and extensively illustrated. Barbara Santich helps us to a deeper understanding of Australian identity by examining the way we eat. Not simply a gastronomic history, her book is also a history of Australia and Australians.

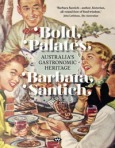

It is a gorgeous book, with (as you can see from the cover art) a nostalgic Women’s Weekly kind of feel to it. It’s full of quaint illustrations and snippets culled from old magazines, newspaper ads, journals and recipe books, and it’s nice just to browse through and enjoy the pictures, my favourite of which has to be the one of Queen Liz at a 1970s BBQ at Yarralumla. There she is, the scarf on her head and the one round Phil’s neck showing just how cold it must have been, dubiously eyeing off the snags and chops. A handsome aide-de-chef in a three-piece suit and a Beatles haircut is nearby with a glass of beer at the ready and the chef (with tattoos of obviously naval origin) is about to put her choice on the (china) plate she’s clutching. It’s a brave attempt to look like an Aussie, which is almost successful except for her too-posh macintosh and the partially obscured lackey sporting the royal crest on his breast-pocket.

In the chapter on Bush Tucker, I like this homage to Australian pioneer women too:

One cannot help but admire the early pioneer women with their adventurous palates who so enthusiastically engaged with a foreign landscape, an untested environment. Many new arrivals took genuine pleasure in sampling the resources around them, much as modern travellers might seek out new foods when visiting markets in foreign countries. Forging a new life in the bush would not have been easy – coping with drought and flood and heat and dust, in long sleeves and long skirts and shoes and stockings, often without a cooking stove or even an indoors kitchen… (p63)

Guided by the maxim of a Mrs Rawson of Queensland that ‘Whatever the blacks eat, the whites may safely try’ (p48) pioneers tried ‘magpie, ibis, kangaroo rat, flying fox, bandicoot, echidna and wombat’ but people were apparently less ready to try unfamiliar plants. (The book features lovely botanical drawings of native edible plants too). From early days women recorded recipes in journals, shared recipes in letters and wrote cookbooks of one sort or another, but (quite apart from any environmental considerations and laws to protect endangered species) Santich suggests that ‘one would have to be desperate to eat ibis’. According to Louisa Meredith of Tasmania magpie is a failure too:

after exhausting all my culinary skill upon them in roasts, stews, curries and pies, I have finally given up on them as not cookable, or rather as not relishable when cooked’. (p46)

Louisa’s culinary adventures, however, relied on adapting Australian ingredients to methods she knew: roasts, stews, curries and pies, and she was not alone. Santich ascribes the 20th century disenchantment with indigenous foods not just to diminishing availability because of unsustainable practices, but also because few took any notice of Aboriginal methods of making these foods palatable. By the time I was cooking as a young bride indigenous foods (apart from fish and seafood, that is) were off the menu except as a rare and exotic experience reported in a foodie magazine. Macadamia nuts were the only native food to be produced in commercial quantities, and although now in the 21st century there is a range of about 60 bush foods available, their use isn’t mainstream. (Perhaps Masterchef could do something about that? Apparently people flock to try out recipes they’ve seen contestants cook.)

There is an interesting chapter about the evolution of the picnic in Australia. Reproductions in this book show that the picnic has often been a subject for painting from the earliest days and according to Santich, picnic fare hasn’t changed all that much: bread and meat, often travelling separately rather than in the form of sandwiches; tomatoes and lettuce, cake and fruit. (p101) Today the bread reflects our multicultural society so we take baguettes, ciabatta or pide; the meat isn’t just ham but also salami, mortadella or chorizo; and dips (hummus, tzatziki and guacamole) come along as well as the tom-and-iceberg, but the basis of the meal is more-or-less the same: ‘uncomplicated, unambitious, uncontrived and in ample quantities’. (p102)

The author also traces the evolution of the barbecue from the ‘chop picnic’ to the monumental gas BBQs we see today along with patriotic exhortations to eat meat on Australia Day. And to my delight, she also notes that

In the novels of Patrick White, the lamb chop is a recurring motif, in particular the distinctive aroma of the grilled lamb chop, stimulating remembrances as sharp and clear as the madeleine for Proust, or as in The Eye of the Storm’ signifying the inevitability of fate. (p183)

There are all kinds of fascinating culinary anecdotes from the ’emblematic’ Anzac biscuit to Lady Flo’s pumpkin scones. Pie ‘n’ sauce and other ‘street foods’ i.e. take-away get a whole chapter to themselves but in an era when Australian manufacturing is under siege, the most nostalgic chapter of all is the one entitled ‘Made in Australia’. When I was a child, Aussie biscuits and sweets, Aussie jams and marmalades, Aussie condiments and sauces were everywhere, all made in Aussie-owned factories, and the range, choice and quality were superb. There was a real cake shop in every shopping centre, and bakeries had their own distinctive recipes, not like today’s bland chains and supermarkets serving the same old stuff everywhere.

This is a fascinating book. Who needs Mother’s Day? Buy it for yourself if you’re interested in Aussie culture and history!

Author: Barbara Santich

Title: Bold Palates: Australia’s Gastronomic Heritage

Publisher: Wakefield Press 2012

ISBN: 9781743050941

Source: Review copy courtesy of Wakefield Press

PS You can view an extract at the publisher’s website. Click the link to Wakefield Press below.

Availability:

Fishpond:Bold Palates: Australia’s Gastronomic Heritage

Or direct from Wakefield Press

Enjoyed your review very much, Lisa. Food is a good way of getting inside a cutural history. But I have to ask: do you fancy the challenge of creating a palatable dish from ibis?!

And I love that retro cover.

In the UK people are fascinated by the idea of wild (free) food, and there are books to reflect that. Unfortunately this can lead to the countyside being stripped of natural resources required by other species. We tried making hawthorn jerky a year or so ago (hard, chewy, not much flavour, and labour intensive, but the kids liked it!) a la Ray Mears, but it was a one off experiment. (The birds need the berries and we don’t.)

LikeLike

By: Sarah on May 7, 2012

at 8:27 pm

Yes, I can see that it would be a problem if it became a fad and people scoured the countryside and stripped it bare.

There is a restaurant here in Melbourne called Attica, which specialises in ‘found food’. The Spouse and I went there for our 20th wedding anniversary and it was very interesting.

But scavenging is not what Santich is suggesting, rather that indigenous plants such as wattleseed be farmed and produced in commercial quantities. She is interested in the idea of developing a ‘national dish’ that really is Australian.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on May 7, 2012

at 9:30 pm

I can only agree with sarah I think this is a gap in the market use food to study past lives ,how we ate I loved a uk series where two people went back and live a week on diets from various times ,great review Lisa ,all the best stu

LikeLike

By: winstonsdad on May 9, 2012

at 5:47 am

Thanks, Stu, I enjoy these kinds of ‘domestic histories’ about life for ordinary people.

LikeLike

By: Lisa Hill on May 9, 2012

at 8:09 am

[…] but this one is different. That was more of a social history of food and cooking, in the style of Bold Palates, Australian’s Gastronomic Heritage, but (as is obvious from the title) with a Melbourne focus. This new Flavours of Melbourne does […]

LikeLike

By: Flavours of Melbourne, by Jonette George, Daniele Wilton, and Brad Hill | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on March 16, 2014

at 9:59 pm

[…] Gastronomic Heritage was shortlisted for the 2013 Preime Minister’s Awards and you can read my review here. (And, oh *blush*, you can see that I ‘reviewed’ that one too before I’d […]

LikeLike

By: Enjoyed for Generations, The History of Haigh’s Chocolates, by Barbara Santich | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on December 8, 2015

at 8:39 pm

[…] Bold Palates: Australia’s Gastronomic Heritage, (2012) by Barbara Santich see my review […]

LikeLike

By: Wild Asparagus, Wild Strawberries, by Barbara Santich #BookReview | ANZ LitLovers LitBlog on August 26, 2018

at 9:27 pm